Schools Use Student Data to Find Signs of Trouble, Help Struggling Kids

By Sammy Mack

At Miami Carol City Senior High in Florida, a handful of teachers, administrators and coaches are gathered around a heavy wooden table in a conference room dubbed the “War Room,” looking through packets of information about several students.

There are others at the table, too: analysts from the group Talent Development Secondary, which monitors student data; City Year, a nonprofit that provides mentors; and Communities in Schools, which connects kids with health care and social services.

It’s a lot of cooks in the kitchen, but they’re all here to help students who are just starting to show signs of trouble.

The process works like this: analyst Jennifer Savino gathers information on attendance, behavior and performance in math and English. Then, based on some dropout risk studies from Johns Hopkins University, she flags kids who are on a downward trend. Those names show up on PowerPoint slides at these weekly War Room meetings.

Today, there are three kids on the list. A projector beams one student’s image on a screen, accompanied by a spreadsheet of his grades so far this year. His most recent report card shows a lot more D’s and F’s than in the first part of the year.

“He came to me last week and he said, ‘I’m hungry. I haven’t had anything to eat all day,’ ” says one teacher. “I had a bag of chips and I gave them to him.”

“If that happens again … we keep snacks in the office,” offers another.

A third person points out something not everyone knows about this student: Turns out, he’s spent more than a week this semester living in a car.

The team then discusses some potential options, like strategies for helping the student manage his time and putting him in touch with homeless services. A sports coach volunteers to coordinate everything.

This kind of interaction between different school departments didn’t happen before.

“If we don’t get to the core of the problem, we can’t teach them,” says Tracy Troy, who teaches math and special education.

USING DATA TO CREATE EARLY WARNING SYSTEM

When these meetings were first introduced three years ago, Troy, who has been on staff at Carol City for 14 years, was apprehensive about getting involved with students’ problems outside her classroom.

“Not that I don’t care, but I care too much,” she says. “And sometimes, it weighs on you. Because those are your children while you’re here.”

Now, she says, the War Room meetings help her help the kids.

The program, called Diplomas Now, identifies 150 to 200 students a year at Carol City. It costs about $600 per student annually to run.

Last school year, one-third of students flagged for missing school got back on track to graduation. Two-thirds of the students who were having behavioral problems made a turnaround.

“The point of all this isn’t to collect data. It’s to change what’s happening for individual kids,” says Paige Kowalski, a state policy director for the Data Quality Campaign, a group that advocates for better use of all that student information the states collect.

Kowalski says about 20 states have developed early warning systems like the one here at Carol City. Schools, she says, can learn a lot from the medical field, in particular.

“[They] don’t just put out reports saying, ‘The hospital lost all these patients and saved these people,’ ” she says. “They actually look at it and say, ‘What can we do better?’ ”

FINDING KIDS WHO MIGHT GET MISSED

Earlier this year, Mack Godbee, a soft-spoken Carol City High 10th-grader, was the subject of a War Room meeting. The first quarter of the school year, Godbee’s report card was littered with D’s and F’s.

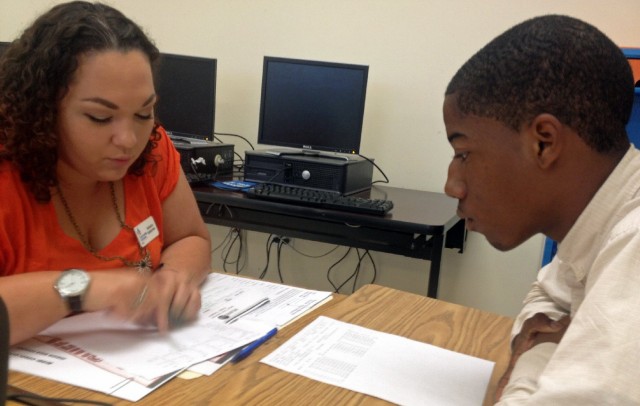

Today, it’s report card time again, and Godbee is going over his most recent grades with his mentor, Natasha Santana-Viera. Now, there are more C’s and B’s, and he got an A in English.

Godbee says his life would be very different if he had not participated in the Diplomas Now program. “No lie — I think I would have ended up dead,” he says.

That’s because he was spending a lot of time on the street. When his dad left home, he explains, he wanted to show his mom that they didn’t need him. So Godbee started selling drugs. He was 6.

By the time he got to high school, Godbee says, he was affiliated with a gang. He skipped classes, didn’t study and was angry all the time.

That might have been easy for teachers and administrators to miss. But earlier this school year, after looking at Godbee’s data, Santana-Viera sat him down and asked, “Are you OK?”

“I sat right there and thought about it. Like, am I really OK?” Godbee recalls.

And for the first time in his life, he said no.

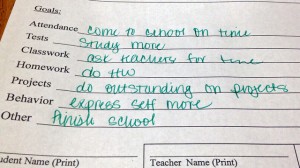

Even with his improvements this year, Godbee doesn’t want to be the person he is now. “I want to be a different person. I want to be that kid that makes straight A’s and B’s on his report card,” he says. “Be in school every day on time. Be on that honor roll list. Go on field trips.”

Godbee has a lot to work on, but according to the data, he’s on an upward trend.