By Stephanie Simon

NEW YORK, Aug 1 (Reuters) – The investors gathered in a tony private club in Manhattan were eager to hear about the next big thing, and education consultant Rob Lytle was happy to oblige.

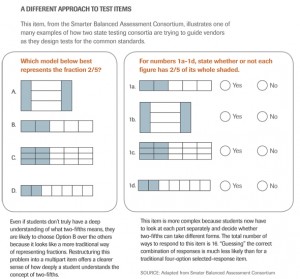

Think about the upcoming rollout of new national academic standards for public schools, he urged the crowd. If they’re as rigorous as advertised, a huge number of schools will suddenly look really bad, their students testing way behind in reading and math. They’ll want help, quick. And private, for-profit vendors selling lesson plans, educational software and student assessments will be right there to provide it.

“You start to see entire ecosystems of investment opportunity lining up,” said Lytle, a partner at The Parthenon Group, a Boston consulting firm. “It could get really, really big.”

Indeed, investors of all stripes are beginning to sense big profit potential in public education.

The K-12 market is tantalizingly huge: The U.S. spends more than $500 billion a year to educate kids from ages five through 18. The entire education sector, including college and mid-career training, represents nearly 9 percent of U.S. gross domestic product, more than the energy or technology sectors.

Traditionally, public education has been a tough market for private firms to break into — fraught with politics, tangled in bureaucracy and fragmented into tens of thousands of individual schools and school districts from coast to coast.

Now investors are signaling optimism that a golden moment has arrived. They’re pouring private equity and venture capital into scores of companies that aim to profit by taking over broad swaths of public education.

The conference last week at the University Club, billed as a how-to on “private equity investing in for-profit education companies,” drew a full house of about 100.

OUTSOURCING BASICS

In the venture capital world, transactions in the K-12 education sector soared to a record $389 million last year, up from $13 million in 2005. That includes major investments from some of the most respected venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, according to GSV Advisors, an investment firm in Chicago that specializes in education.

The goal: an education revolution in which public schools outsource to private vendors such critical tasks as teaching math, educating disabled students, even writing report cards, said Michael Moe, the founder of GSV.

“It’s time,” Moe said. “Everybody’s excited about it.”

Not quite everyone.

The push to privatize has alarmed some parents and teachers, as well as union leaders who fear their members will lose their jobs or their autonomy in the classroom.

Many of these protesters have rallied behind education historian Diane Ravitch, a professor at New York University, who blogs and tweets a steady stream of alarms about corporate profiteers invading public schools.

Ravitch argues that schools have, in effect, been set up by a bipartisan education reform movement that places an enormous emphasis on standardized test scores, labels poor performers as “failing” schools and relentlessly pushes local districts to transform low-ranked schools by firing the staff and turning the building over to private management.

President Barack Obama and both Democratic and Republican policymakers in the states have embraced those principles. Local school districts from Memphis to Philadelphia to Dallas, meanwhile, have hired private consultants to advise them on improving education; the strategists typically call for a broader role for private companies in public schools.

“This is a new frontier,” Ravitch said. “The private equity guys and the hedge fund guys are circling public education.”

Some of the products and services offered by private vendors may well be good for kids and schools, Ravitch said. But she has no confidence in their overall quality because “the bottom line is that they’re seeking profit first.”

Vendors looking for a toehold in public schools often donate generously to local politicians and spend big on marketing, so even companies with dismal academic results can rack up contracts and rake in tax dollars, Ravitch said.

“They’re taking education, which ought to be in a different sphere where we’re constantly concerned about raising quality, and they’re applying a business metric: How do we cut costs?” Ravitch said.

BUDGET PRESSURES

Investors retort that public school districts are compelled to use that metric anyway because of reduced funding from states and the soaring cost of teacher pensions and health benefits. Public schools struggling to balance budgets have fired teachers, slashed course offerings and imposed a long list of fees, charging students to ride the bus, to sing in the chorus, even to take honors English.

The time is ripe, they say, for schools to try something new — like turning to the private sector for help.

“Education is behind healthcare and other sectors that have utilized outsourcing to become more efficient,” private equity investor Larry Shagrin said in the keynote address to the New York conference.

He credited the reform movement with forcing public schools to catch up. “There’s more receptivity to change than ever before,” said Shagrin, a partner with Brockway Moran & Partners Inc, in Boca Raton, Florida. “That creates opportunity.”

Speakers at the conference identified several promising arenas for privatization.

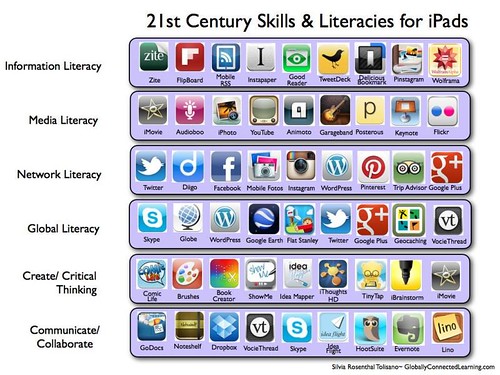

Education entrepreneur John Katzman urged investors to look for companies developing software that can replace teachers for segments of the school day, driving down labor costs.

“How do we use technology so that we require fewer highly qualified teachers?” asked Katzman, who founded the Princeton Review test-prep company and now focuses on online learning.

Such businesses already have been drawing significant interest. Venture capital firms have bet more than $9 million on Schoology, an online learning platform that promises to take over the dreary jobs of writing and grading quizzes, giving students feedback about their progress and generating report cards.

DreamBox Learning has received $18 million from investors to refine and promote software that drills students in math. The software is billed as “adaptive,” meaning it analyzes responses to problems and then poses follow-up questions precisely pitched to a student’s abilities.

The charter school chain Rocketship, a nonprofit based in San Jose, California, turns kids over to DreamBox for two hours a day. The chain boasts that it pays its teachers more because it needs fewer of them, thanks to such programs. Last year, Rocketship commissioned a study that showed students who used DreamBox heavily for 16 weeks scored on average 2.3 points higher on a standardized math test than their peers.

SPECIAL ED AS A GROWTH MARKET

Another niche spotlighted at the private equity conference: special education.

Mark Claypool, president of Educational Services of America, told the crowd his company has enjoyed three straight years of 15 percent to 20 percent growth as more and more school districts have hired him to run their special-needs programs.

Autism in particular, he said, is a growth market, with school districts seeking better, cheaper ways to serve the growing number of students struggling with that disorder.

ESA, which is based in Nashville, Tennessee, now serves 12,000 students with learning disabilities or behavioral problems in 250 school districts nationwide.

“The knee-jerk reaction [to private providers like ESA] is, ‘You’re just in this to make money. The profit motive is going to trump quality,’ ” Claypool said. “That’s crazy, because frankly, there are really a whole lot easier ways to make a living.” Claypool, a former social worker, said he got into the field out of frustration over what he saw as limited options for children with learning disabilities.

Claypool and others point out that private firms have always made money off public education; they have constructed the schools, provided the buses and processed the burgers served at lunch. Big publishers such as Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt have made hundreds of millions of dollars selling public school districts textbooks and standardized tests.

Critics see the newest rush to private vendors as more worrisome because school districts are outsourcing not just supplies but the very core of education: the daily interaction between student and teacher, the presentation of new material, the quick checks to see which kids have risen to the challenge and which are hopelessly confused.

At the more than 5,500 charter schools nationwide, private management companies — some of them for-profit — are in full control of running public schools with public dollars.

“I look around the world and I don’t see any country doing this but us,” Ravitch said. “Why is that?”