How to be effective when studying….

(CNN)-

If you think you are tech savvy all because you know what “LOL” means, let me test your coolness.

Any idea what “IWSN” stands for in Internet slang?

It’s a declarative statement: I want sex now.

If it makes you feel any better, I had no clue, and neither did a number of women I asked about it.

Acronyms are widely popular across the Internet, especially on social media and texting apps, because, in some cases, they offer a shorthand for communication that is meant to be instant.

So “LMK” — let me know — and “WYCM” — will you call me? — are innocent enough.

But the issue, especially for parents, is understanding the slang that could signal some dangerous teen behavior, such as “GNOC,’” which means “get naked on camera.”

And it certainly helps for a parent to know that “PIR” means parent in room, which could mean the teen wants to have a conversation about things that his or her mom and dad might not approve of.

Katie Greer is a national Internet safety expert who has provided Internet and technology safety training to schools, law enforcement agencies and community organizations throughout the country for more than seven years.

She says research shows that a majority of teens believe that their parents are starting to keep tabs on their online and social media lives.

“With that, acronyms can be used by kids to hide certain parts of their conversations from attentive parents,” Greer said. “Acronyms used for this purpose could potentially raise some red flags for parents.”

But parents would drive themselves crazy, she said, if they tried to decode every text, email and post they see their teen sending or receiving.

“I’ve seen some before and it’s like ‘The Da Vinci Code,’ where only the kids hold the true meanings (and most of the time they’re fairly innocuous),” she said.

Still, if parents come across any acronyms they believe could be problematic, they should talk with their kids about them, said Greer.

But how, on earth, is a parent to keep up with all these acronyms, especially since new ones are being introduced every day?

“It’s a lot to keep track of,” Greer said. Parents can always do a Google search if they stumble upon an phrase they aren’t familiar with, but the other option is asking their children, since these phrases can have different meanings for different people.

“Asking kids not only gives you great information, but it shows that you’re paying attention and sparks the conversation around their online behaviors, which is imperative.”

Micky Morrison, a mom of two in Islamorada, Florida, says she finds Internet acronyms “baffling, annoying and hilarious at the same time.”

She’s none too pleased that acronyms like “LOL” and “OMG” are being adopted into conversation, and already told her 12-year-old son — whom she jokingly calls “deprived,” since he does not have a phone yet — that acronym talk is not allowed in her presence.

But the issue really came to a head when her son and his adolescent friends got together and were all “ignoring one another with noses in their phones,” said Morrison, founder of BabyWeightTV.

“I announced my invention of a new acronym: ‘PYFPD.’ Put your freaking phone down.”

LOL!

But back to the serious issue at hand, below are 28 Internet acronyms, which I learned from Greer and other parents I talked with, as well as from sites such as NoSlang.com and NetLingo.com, and from Cool Mom Tech’s 99 acronyms and phrases that every parent should know.

After you read this list, you’ll likely start looking at your teen’s texts in a whole new way.

1. IWSN – I want sex now

2. GNOC – Get naked on camera

3. NIFOC – Naked in front of computer

4. PIR – Parent in room

5 CU46 – See you for sex

6. 53X – Sex

7. 9 – Parent watching

8. 99 – Parent gone

9. 1174′ – Party meeting place

10. THOT – That hoe over there

11. CID – Acid (the drug)

12. Broken – Hungover from alcohol

13. 420 – Marijuana

14. POS – Parent over shoulder

15. SUGARPIC – Suggestive or erotic photo

16. KOTL – Kiss on the lips

17. (L)MIRL – Let’s meet in real life

18. PRON – Porn

19. TDTM – Talk dirty to me

20. 8 – Oral sex

21. CD9 – Parents around/Code 9

22. IPN – I’m posting naked

23. LH6 – Let’s have sex

24. WTTP – Want to trade pictures?

25. DOC – Drug of choice

26. TWD – Texting while driving

27. GYPO – Get your pants off

28. KPC- Keeping parents clueless

Editor’s note: Tim Magner is the executive director of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills (P21), a national organization that advocates for 21st-century readiness for every student. He has had an extensive career in education, serving most recently as the vice president of Keystone for KC Distance Learning (KCDL) as well as the director of the Office of Educational Technology for the U.S. Department of Education.

______________________________________________________________________

(CNN) – Whether it’s technology, the global economy or the changing nature of work itself, we are tasked with preparing our children for success in college, career and citizenship in a world that looks very different from the one we grew up in. I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with P21’s members, partners and leadership states to help educators embed key 21st-century skills – like the four Cs of communication, collaboration, creativity and critical thinking – into the educational experiences of all children.

Our children need these 21st-century skills not simply because employers are looking for them (they are), or because they are essential for success in college (they are), or because other nations are also recognizing this skills gap (they are), but because we want our children to not just survive in this new millennium, but to truly thrive.

21st-century readiness – having the knowledge and skills to pursue further education, compete in the global economy and contribute to society – demands much more of all of our students, and our education system must change to meet these demands. Recognizing this fundamental shift, the ongoing Common Core State Standards initiatives are embedding these skills into the new standards frameworks.

This is what makes the recently released Next Generation Science Standardsfrom the National Research Council particularly exciting, because they recognize these important shifts and make wise suggestions to integrate deep-content knowledge with the skills to apply that knowledge.

The science standards explore a range of active approaches to learning, from asking questions and defining problems to using models, carrying out investigations, analyzing and interpreting data, designing solutions and using evidence. These practices are not only essential science skills, but also form the core elements of the critical thinking and problem solving skills of P21’sFramework for 21st Century Learning.

21st-century readiness demands much more of all of our students, and our education system must change to meet these demands.

The standards also highlight the importance of communicating information as a scientific practice, and they recognize the importance of teamwork and collaboration by including collaboration and collaborative inquiry and investigation, beginning in kindergarten.

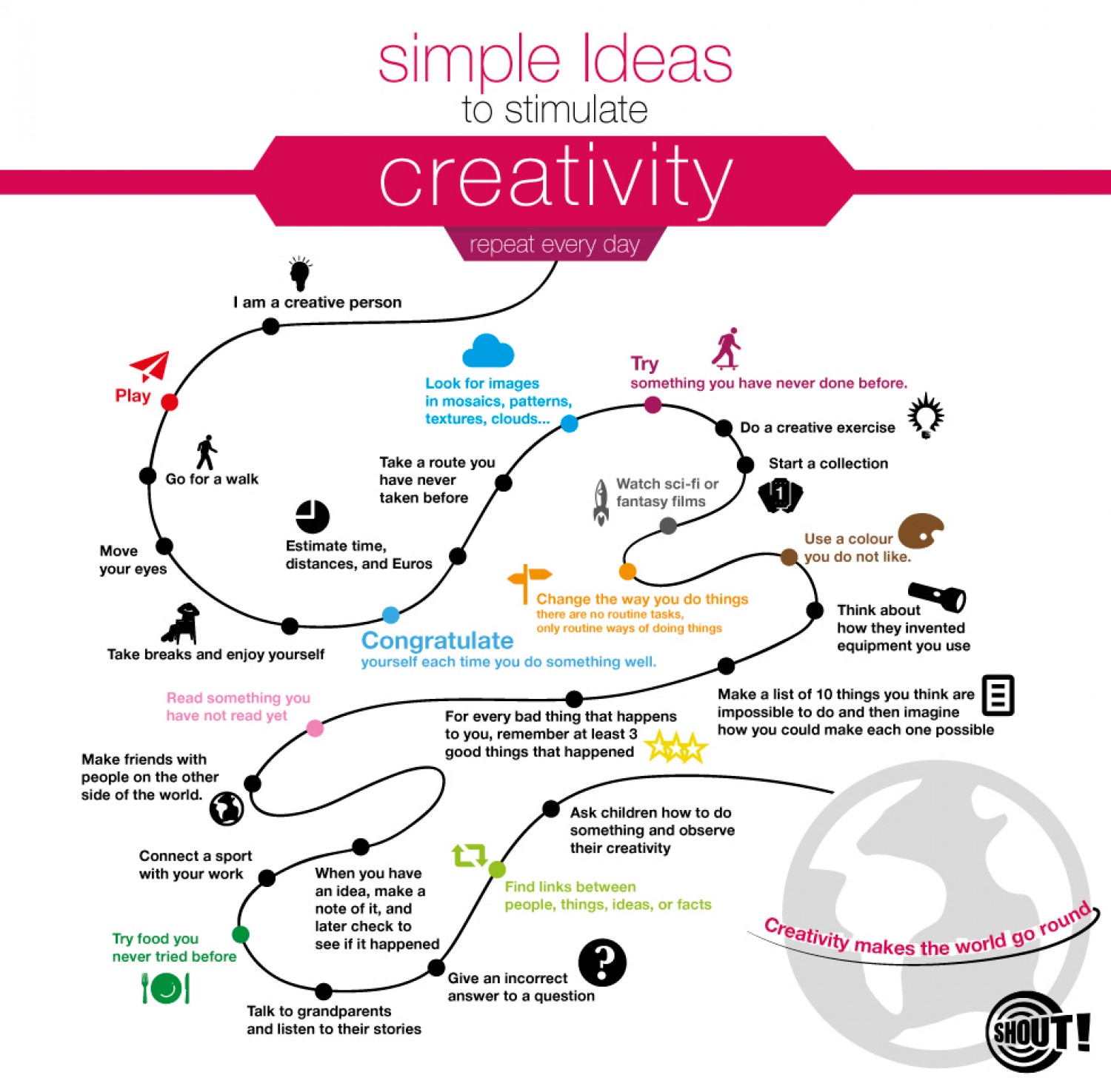

Where I wish the standards were stronger is in creativity and innovation. Much of our economic success over the past century has been because of breakthroughs in science and technology. I hope that as these standards are implemented, science educators will work hard to infuse them with opportunities for students to see science as a creative endeavor. Science class could become a chance to invent the next generation of medicines, electronics or the myriad other innovations we will need to feed, clothe, power and empower our planet.

Ideally, these standards will help redefine the science classroom and science experience for the 21st century. I’d like to see science classrooms look more like the spaces created by the Community Science Workshop Network. In these models, students are free to explore and experiment with a wide range of materials – discovering not just science facts, but science joy. If our children are excited by science, rather than frightened by it, our ability to encourage more of them to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics – the so-called STEM fields – would be immeasurably enhanced.

The new Next Generation Science Standards can and should be implemented with an emphasis on creativity. Combined with the “flipped classroom” model – where technology delivers information at home so face-to-face time in school can be focused on actual creating, making and doing – science educators have the opportunity to transform the spaces where science happens and redefine the school-based science experience. Classroom discussions, hands-on experimentation and collaborative explorations can become the norm for all children.

And it comes not a moment too soon. We are facing increasingly complex problems in the world around us – from pressures on our food and water, to environmental challenges, to ever more complex engineering problems, to the basic health needs of growing populations. In these very real challenges, there are plenty of opportunities for creative scientific exploration that connects the classroom to the outside world.

The 21st-century classroom should be a place where students get to start exploring their world, discovering their passion, applying what they know and beginning to experience the impact they can have. I’m optimistic that in the hands of talented science educators, conceptual shifts like those in the science standards will make these aspirations a reality for many more of our nation’s students.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Tim Magner.

As I sit at my desk I can hear the distant hum of a photocopier, a mobile phone vibrates along a table and somewhere far away a printer runs out of paper.

The office has become a very quiet place indeed.

Technology has changed the sound of office life. For a hundred years it was a noisy place, filled with the sound of telephones and typewriters. Now it is almost silent – just broken by the gentle sound of someone saying: “Nipping out to get a latte. D’you want one?”

In the beginning there were just paper and quills. Then came the typewriter, which brought with it a number of other late 19th Century breakthroughs – the filing cabinet, the adding machine, and in particular the telephone.

But what did these inventions mean? And did they make office life better or worse?

In the stores at the Museum of London there is a sort of giant graveyard full of old office machinery. Row after row of adding machines fill the shelves.

The earliest model is the Burroughs adding machine, which could calculate relatively complicated sums with its rows of keys and pull handle.

The telegraph was the Victorian internet. It made the world global. It meant you could do business without actually being there.

Another breakthrough came in 1870 – the filing cabinet. In the dark ages before this simple bit of furniture was invented, clerks wrote everything down in massive ledgers and on pieces of paper tied up in bundles. If the clerk left or died suddenly, any chances of finding anything often died with him.

With the cabinet, information could be arranged alphabetically, which meant it was theoretically possible to find it again. That was great – what wasn’t so great is that this created an entire industry of unnecessary work.

I worked as a filing clerk briefly in the late 1970s and there was nothing more dispiriting than stuffing paper into bulging files knowing perfectly well that no-one would ever look at it again.

On one estimate, the UK in the pre-computer age shoved more than two million tonnes of paper into filing cabinets every year. Unnecessarily.

These new devices increased efficiency but didn’t really change the nature of business.

Then came the telegraph.

“What hath God wrought,” said the first long-distance telegraph by Morse Code in 1844. And what God had wrought turned out to be a very big deal indeed.

The telegraph was the Victorian internet. It made the world global. It meant you could do business without actually being there. It released the manager from the factory. It meant that the prices on the Paris stock exchange were known the same day in London.

The spread of the telegraph was almost as fast as Facebook today. By 1887, 50 million of them were being sent a year in the UK, almost all for business.

The beauty of the telegraph was that it invented brevity long before Twitter made it cool. But it also invented scarcity. Because it was expensive in its earliest form – it was the equivalent of about £80 today – you only sent a telegram if you actually had something to say. Would that were the case today.

But in 1876 came the telephone, and with it a new sort of behaviour. The telephone created an informality that the telegraph never aspired to.

The telephone made business big. Easy communication encouraged the growth of sprawling multinationals with offices everywhere. It also made them tall – without it the skyscraper never would have caught on.

As one AT&T engineer put it in 1900: “Suppose there was no telephone and every message had to be carried by a personal messenger. How much room do you think the necessary elevators would leave for offices?”

In the US they couldn’t get enough of the phone. By the end of the 1920s, 40% of households had them.

Telephones made business democratic – a man on the factory floor could talk directly with the boss without having to go through all the levels in between.

“It gives a common meeting place to capitalists and wageworkers,” wrote Herbert Casson in his 1910 book The History of the Telephone.

In the stores at the Museum of London there is a sort of giant graveyard full of old office machinery. Row after row of adding machines fill the shelves.

“It is so essentially the instrument of all the people, in fact, that we might almost point to it as a national emblem, as the trademark of democracy and the American spirit.”

The enthusiasm wasn’t shared in the UK. William Preece, chief engineer of the General Post Office, declared that the new gizmo was merely “a substitute for servants”.

“There are conditions in America which necessitate the use of such instruments more than here,” he told a House of Commons committee.

“Here we have a super-abundance of messengers, errand boys and things of that kind. The absence of servants has compelled America to adopt communications systems for domestic purposes. Few have worked at the telephone much more than I have, I have one in my office but more for show. If I want to send a message – I employ a boy to take it.”

By 1880, the first ever British phone directory had a mere 285 names – all of them London business, and mostly traders, dealing in everything from sugar to ostrich feathers.

The Bank of England, never one to hurry into anything, was not connected until 1902 but then they were still buying quills till 1907.

The merchant bank Schroders refused to have its name in the telephone directory, for fear that incoming calls caused distraction.

And at the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, the phone was regarded with such suspicion that operators had to answer with the words, “I am the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank”.

People worried that the phone took away their privacy, in much the same way that we now fret over social networking. But by 1927, telephone calls were flooding in at an average of one every 1.5 days.

Women were the new masters of the telephone, just as they were with the typewriter. A new kind of an office was emerging – the telephone exchange – and women were deemed just the people to operate it.

“The dulcet tones of the feminine voice seem to exercise a soothing and calming effect upon the masculine mind,” noted an early telephone engineer.

There was actually nothing soothing about working a switchboard. It was relentless and exhausting, involving cumbersome apparatus and the speedy plugging and unplugging of cords at various heights and, of course, dealing with the public, who weren’t easy to please.

The Times complained about uppity switchboard girls. “Too many of the operators seem to regard the telephone user as their natural enemy and treat him with utter nonchalance, if not with an insolence and impertinence, which are all the more irritating because there appears at present to be no remedy for them.”

The telephone made business big. Easy communication encouraged the growth of sprawling multinationals with offices everywhere.

The new technology meant a new etiquette. In 1910, the telephone company Bell put out a booklet called Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde at the Telephone.

Some of its lessons were simple – “Speak directly into the mouthpiece keeping moustache out of the opening” – advice I’ve always followed.

Saying hello was much frowned upon too.

“Would you rush into an office or up to the door of a residence and blurt out ‘Hello! Hello! Who am I talking to?’” asked Bell. “One should open conversations with phrases such as ‘Mr Wood, of Curtis and Sons, wishes to talk with Mr White…’ without any unnecessary and undignified ‘hellos’.”

And as for ending a call, a 1926 telephone magazine advised that it was up to the caller to signal the end, unless a man and a woman were speaking, in which case it was up to the “second sex” to ring off first.

But that was all in the US. The UK, meanwhile, continued to lag behind. In 1914, we had the worst telephone service in the civilised world, according to the Quarterly Review.

There were then fewer than two telephones per 100 people in the UK compared with 10 in US. It was not until after 1919 that the telephone really spread.

But by middle of the 20th Century most workers had a phone on their desk. They got used to the constant ringing and interruptions. People didn’t get up to talk to each other, they spoke on the phone instead. The office switchboard was the hub of office, a sort of social glue connecting everyone to everyone else.

And that’s how it stayed – until the last couple of years. We are now witnessing the death of the office landline, and with it the main switchboard.

If anyone really wants me, they send me an email, and because I don’t like random disturbances any more than the Edwardians did, I’ve stopped answering my desk phone altogether.

The other day I checked my voicemail and found 100 messages stretching back over weeks. Guess what I’d missed? Nothing of any note at all.

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Lucy Kellaway’s History of Office Life, produced by Russell Finch, of Somethin’ Else, for Radio 4. Episode five, The Telephone and New Office Technology, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 26 July. Episode six, The Invention of the Manager, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 29 July