via The Journal

Hardly a week has gone by in the last year when educators have not been bombarded by news articles, blog posts, or invitations to attend webinars and conferences focused on the flipped classroom. Flipping has become a hot topic among both educators and school leaders. But there are some legitimate concerns. A major one is the rationale for selecting the flipped method in the first place, which might displace other valuable, technology-based instructional strategies.

A flipped lesson incorporates viewing instructional videos for homework. It’s not the use of video that might make educators skeptical of this strategy, but how and where it is used in instruction and its effect on learners as homework.

Although an instructional video can be a valuable tool, is this current focus on the flip being made at the expense of other technologies that should play a role in instruction? Certainly, if educators are going to create videos for learning, they can’t just “wing-it and post-it” and assume learners will be engaged. If you are skeptical and unsure about trying flipped instruction, particularly for mathematics, the following questions and considerations for the design of instruction involving video might help you decide and avoid a flip-flop.

Initial Questions

Over the last 30 years, many instructional strategies have been introduced aimed at increasing mathematics achievement. “Individualized instruction, cooperative learning, direct instruction, inquiry, scaffolding, computer-assisted instruction, and problem solving” are among those, according to NCTM’s President Linda Gojak (2012, para. 1). Whenever a different strategy comes along, educators wonder about its potential, including for the latest addition–the flipped classroom.

How does flipping work?

A typical cycle might occur over two days. On the first day learners begin their exploration of concepts via an activity that builds on prior knowledge. They would view instructional video that night for homework, which replaces the traditional in-class lecture. The video may or may not involve interactivity. Learners might complete a reflective activity as proof of viewing it. On day 2, discussion ensues so that they get their additional questions answered. Learners then engage in activities for applying their knowledge, working on problem sets from learning packets. They might complete those for day 2 homework and also prepare for an assessment the following day (Saltman, 2011).

An instructional video has advantages, such as the ability to pause and repeat; but but it has disadvantages as well: An instructional video is a lecture, just a different form of “sage on the stage.” It is not by itself learner-centered. And unlike a face-to-face lecture, which might also inspire and be meaningful to learners, it has an additional disadvantage in that learners do not necessarily get their immediate questions answered by a pause and repeat. Learners need interactivity and engagement. Proponents know that. Indeed, Jon Bergmann (2012) views “flipped learning as a transitional pedagogy/technique. We are transitioning from the old industrial model of education to the learner centered, active class of the future” (para. 3). Actually, educators should have made that learner-centered transition well before flipping became the hot topic.

It’s not the use of video that might make educators skeptical of this strategy, but how and where it is used in instruction and its effect on learners as homework.

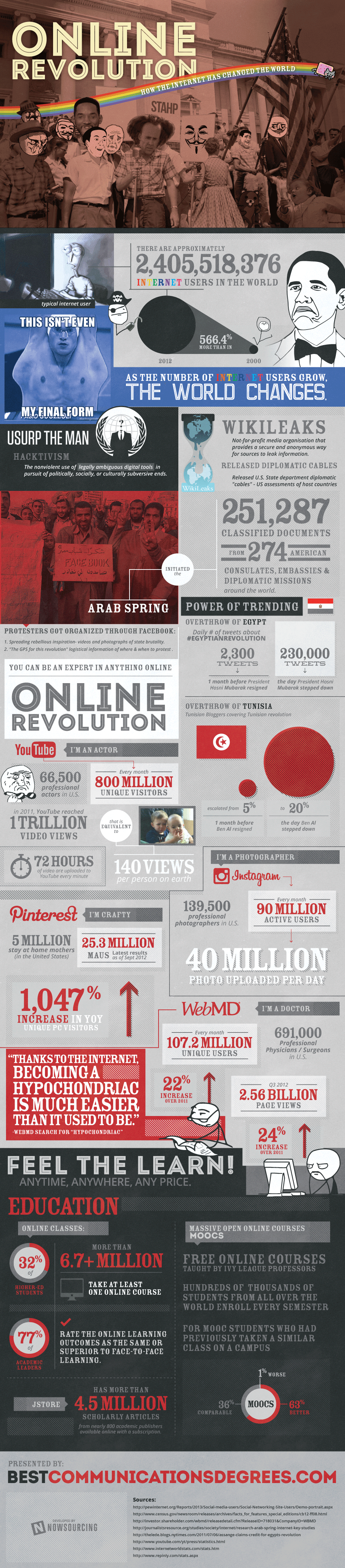

An initial question often surrounds access to appropriate technology for viewing video outside of class time. There’s something to be said for needing one-to-one and BYOD initiatives in connection to success of a flipped class. Even with Internet access at home, what do you tell a family that has only one computer, more than one child, each of whom might have more than one video to view for homework, resulting in lack of time and frustration for each to complete it? Proponents say there are solutions, such as using school computers before or after school, or during the school day in a study hall. Even that has limitations considering that the only transportation to and from school for many is the scheduled school bus. Giving more time during a week to complete viewing the videos is not a complete solution, as without the video lecture there’s a huge gap in learning to fill at day 2 in a flipped class cycle.

Would it be appropriate for all to use instructional video as homework?

The type and amount of homework to assign at each grade level and whether or not to grade it has also been problematic. Consider the extent of diversity among learners, including their varied learning and thinking styles. As they also vary in mathematical maturity (Morsund & Ricketts, 2012), math educators would be particularly interested in the potential for increase in math anxiety from digging into video content alone and the degree to which learners will accept the challenge.

How often and under what circumstances should the method be used? Not all educators have found success in their implementations. There have been learners themselves who rejected the flipped classroom, preferring a traditional approach. Bergmann (2012) indicated that for lower grades, the method might only be appropriate for selected lessons. Shouldn’t this selectivity be considered for all grades?

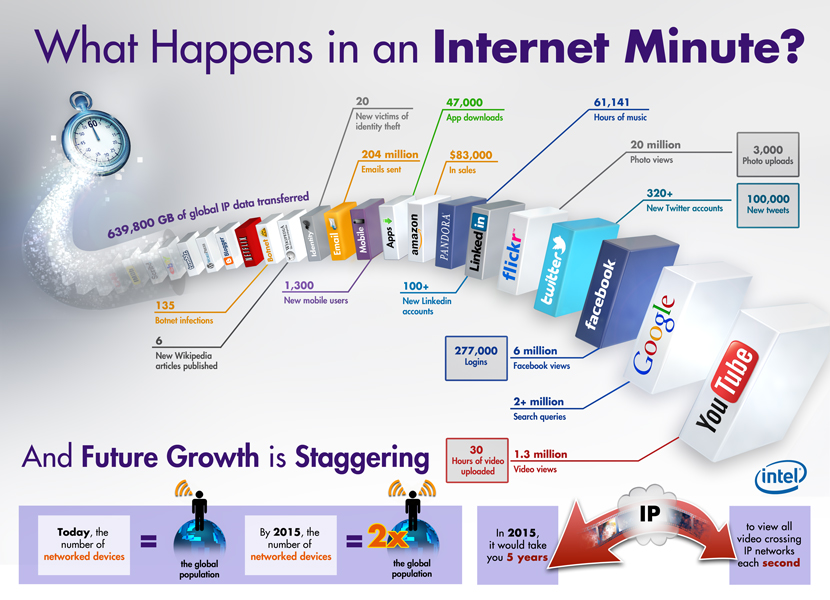

Certainly, a video must convey more than what can be read in a traditional textbook. If all learners had Internet access outside of class time, why would educators want to focus on instructional video for homework? There is a wealth of digital content for teaching and learning mathematics. Types include tutorials, skill builders with drill and practice, comprehensive courseware, test prep, problem-solving challenges, simulations and visualization tools, and serious educational games (Schneiderman, 2006). Some of those offer global challenges with other learners. Add Web 2.0 tools for collaboration. This does not mean that those who flip would not use them, however.

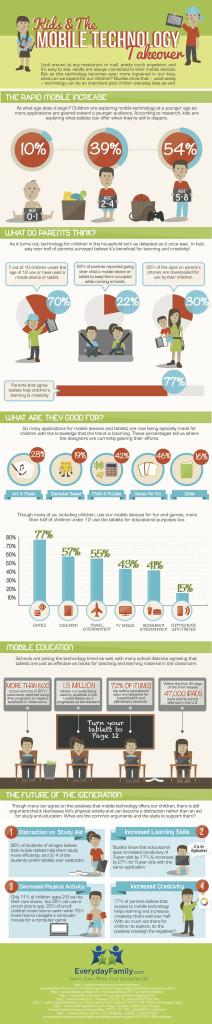

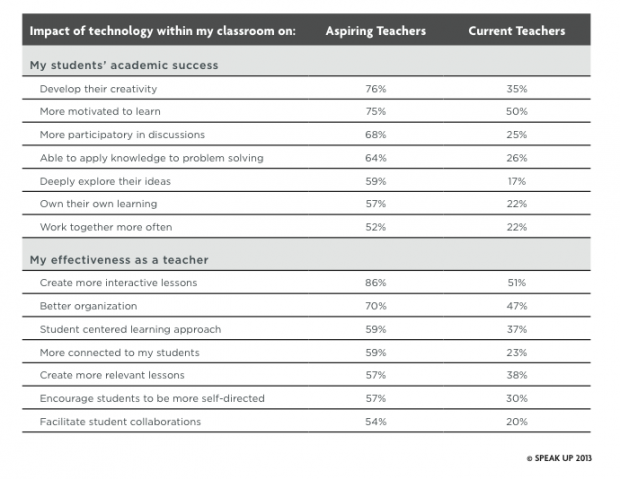

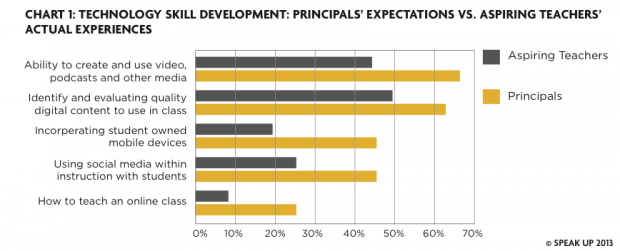

Given limited time for professional development and so many technology options for instruction, educators might also ask where their technology integration priorities should lie. Two years ago, I commented on the need to ensure learners gain expertise using technologies that will be included in upcoming online Common Core assessments. Gray and colleagues found relatively low percentages for technology use in classrooms for such activities (Deubel, 2010). As math homework often involves using paper/pencil to complete problems independently, would this be the best use of time in a flipped class in light of this need to expand technology use? Or, would digital resources be available for such practice, which also track progress?

What evidence is there that the method is effective and leads to student achievement? An entire school has adopted the model owing to data from piloting it, which indicated fewer failures, better discipline, increase in homework completion, and more students reaching proficiency (Saltman, 2011). As everything educators do should lead to achievement, results from a 2010 national online survey by PBS & Grunwald Associates might make one wonder about the longevity of a method that features video. Over 1,400 preK-12 teachers participated. Although 82 percent believed video content is more effective when it is integrated with other instructional resources or content, less than half believed video content directly increases student achievement (42 percent) and is more effective than other types of instructional resources or content (31 percent).