Learning to “Learn” from Failure….

Yesterday’s post on Education Unbound focused on how teachers can better support student learning by embracing, encouraging and supporting failure in the classroom. This might seem shocking to students who don’t want their instructors to be rooting for them to fail, but we are not talking about catastrophic, epic failure, but rather the kinds of small setbacks that encourage learning. What does that mean and how can you, as a student “fail” and still be successful in your educational goals?

Learning from Your Mistakes

We all make mistakes. I once decided that I would be better served by writing on an exam that the professor’s questions about the history of Native American cultures were irrelevant and proceeded to write a long treatise on the current state of indigenous affairs in the U.S. The “D” I received on that exam is a fair indication that I made a rather significant mistake. But did I learn from my mistake? Absolutely. I learned to play the education game a little better, and I learned that I have a passion for Native American affairs that I hadn’t previously realized. I later turned much of the content of that essay into a portion of a course on “Toxic Literacies” that I taught to incoming freshman.

That was, however, a hard-on-the-GPA lesson to learn. I am not advocating radical/stupid failure just to make a point, but rather acknowledging that you will make mistakes and that you should consciously learn from them. When you find yourself on the wrong side of success in the classroom, what should you do to remedy the situation and turn it to your advantage? Here are some strategies for ensuring that your failures make you a success.

Embrace Metacognition

Metacognition is the process of thinking about your thinking. That may sound convoluted, but it makes sense if you take a step back and think about it for a moment. Rather than just accept that you got something wrong, think about why you got it wrong. Take an academic failure for example and ask yourself these questions:

- Was this a mistake you make repeatedly? If so, is that due to some knowledge or information deficiency you have, that you might be able to remedy?

- Did you get it wrong because it is the first time you have ever seen a problem like this? Would practice with similar problems or tasks help build the skills you need?

- Did you not make a serious effort to solve the problem, complete the assignment, or study the material? If not, why not? Be honest with yourself. That is the only way to really uncover why the failure happened.

- Was there a problem with the test, task, or problem that confused you or made the process of succeeding unnecessarily difficult? If so, do you understand the underlying concepts or skills and can you demonstrate them on other tasks?

Thinking clearly and honestly about why you failed at something is the first step in learning from it. If you are unwilling to take a good hard look at your own actions and culpability in your failure, you are unlikely to learn from it. Avoid the temptation to blame others for your shortcomings, you can’t control them, but you can do things to make yourself better. Once you have examined why you think you failed, you are ready to take the next step in learning from the experience – ask the professor for help.

Ask for Help

Contrary to what some students believe, faculty members are there to help you learn. Not just in the lecture hall or lab, but in their offices, the academic quad, or campus coffee shops. More importantly, they want to help you learn. Most of them sit in their office hours and rarely see any students except the ones who are already doing well in their classes. The ones they want to see, however, are the ones who need their help the most.

Once you have a handle on why you are having problems in a class, and if those problems can be overcome by gaining additional clarification from the instructor, or through some focused tutoring on the topic. Contact the professor to schedule an appointment to talk about yourdeficiencies and how he or she can help you overcome them. It is important to realize that, regardless of any perceived lack of clarity on the part of the faculty member, it is your job to learn the material and succeed. Do not blame them for your failure, regardless of what you think the cause may be.

Ask well-targeted questions that help you address the specific issues that you addressed when you thought through your reasons for failing. Talk about studying strategies, alternative sources for the course information, tutoring, or ask for help filling in gaps in your knowledge. Remember, the professor is there to help you, and you should be thankful for their time and consideration. By doing this you are not only getting help with the immediate problem, but also learning how to become and independent learner who seeks help and interacts with those who can assist them. This is also an excellent way to establish a relationship with faculty members who you may consider asking for professional references in the future.

Explore Alternative Paths to Success

This is the one unconventional piece of advice in this post. If you realize that you are having problems because of a failure to make a concerted effort, or because you are having problems understanding core concepts, and asking the instructor for assistance has not helped or isn’t working, consider going outside the normal channels for assistance.

One realistic possibility is that you might have a specific problem learning some types of information. You might consider visiting your student support services office if you are encountering problems with a specific type of learning. They can help diagnose your particular disability and suggest ways of being successful with it.

If you feel that the presentation of the information simply is not a good match for the way you learn best, consider other sources of learning. There is a wealth of information available online and you can find an alternative presentation of almost any course content in online texts, videos, or even interactive tutorials. You just have to look.

The truly radical option here is to step way outside of the box and craft an alternative way to demonstrate your understanding to the faculty member. If you are constantly failing at writing papers for a class but love to make movies, ask the instructor if you can create a short film in place of the final paper. Perhaps a computer animation of the motion of molecules in a particular atom might be an acceptable outcome in a science class? You will never know if some alternative assessment might be possible if you don’t ask. Worst case is they will say “no” and you are back where you started. Best case is that they say “yes,” you wow the professor with what you show them and they see you as a motivated, creative individual whom they are happy to support in future endeavors.

Failing to Learn is the Only Real Failure

All of these suggestions are predicated on one thing – you need to accept failure as a positive experience that helps you grow. If you can examine your shortcomings with some objectivity, you will begin to position yourself to not only overcome them, but to develop lifelong habits of addressing your failings that will make you much more successful in the long run. As Dale Carnegie once said, “Develop success from failures. Discouragement and failure are two of the surest stepping stones to success.”

Managing your digital footprint…

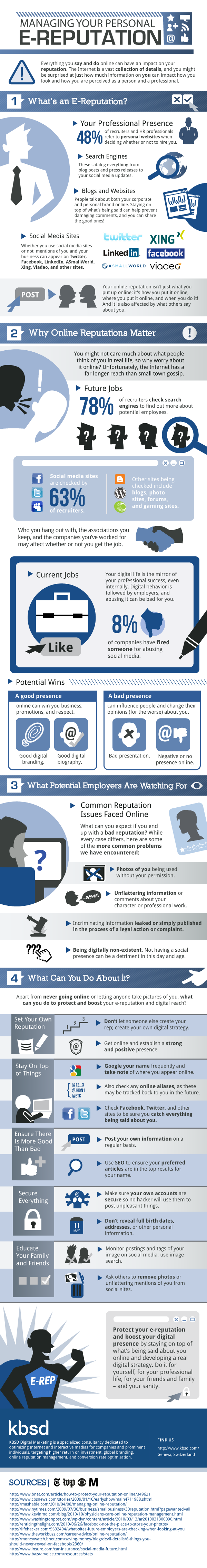

“Everything you say and do online can have an impact on your reputation. The Internet is a vast collection of details, and you might be surprised at just how much information on you can impact how you look and how you are perceived as a person and a professional.”

The infographic is split into 4 sections:

- What is an e-reputation?

- Why online reputations matter

- What potential employers are watching for

- What can you do about it?

I’ve included the final section below, but please please look at the previous ones too (click the image for the full infographic) as the information is well presented and well worth a couple of minutes of your time – if for nothing else so you can be sure you’re doing it right.

“Protect your e-reputation and boost your digital presence by staying on top of what’s being said about you online and developing a real digital strategy. Do it for yourself, for your professional life, for your friends and family – and your sanity.”

More thoughts on effective school technology leadership by @WiscPrincipal

After reading this post by @WiscPrincipal I felt it was important to share it with my followers or readers.

Effective school technology implementation does not occur if there is not effective leadership in place to make it happen. It takes a lot of vision, passion, resources, and coordination, vision, to bring technology (or any new resource or practice) into an organization to make a positive impact on learning and teaching. The school leader is the key player in these areas. Leithwood and Riehl (2003) highlight the importance of school leadership by noting that it is second only to instruction from teachers when it comes to impacting student learning.

I’ll echo Todd Hurst’s thoughts that effective school technology leadership does not differ greatly from good school leadership. Leaders set a vision, share the vision, outline expectations, make goals, and then monitor performance toward that vision (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003). The work of Anderson and Baxter (2005) and Flanagan and Jacobsen (2003) also speak to the importance of the leader having a vision about the use of school technology.

The school leader must have a good understanding of best instructional practices and pay attention to their effect on student learning. The use of technology can be considered a best instructional practice, but tech use can’t be “business as usual with computers” (Bosco, 2003; p. 15). Flanagan and Jacobson (2003) share that, “Merely installing computers and networks in schools is insufficient for educational reform” (p. 125). We need to move past the focus on acquisition of resources, and put work into using those resources to have an impact on learning (Bosco, 2003). This type of instructional shift is where leadership really matters.

The provision of staff development has been identified as an important school leadership factor by Leithwood and Riehl (2003), and is also noted as key for the implementation of effective school technology programs. Bosco (2003) shares that professional development is essential for schools to move beyond the mere presence of computers, to effectively using them as a teaching and learning tool. Flanagan and Jacobsen (2003) show how student technology use progresses from productivity, to foundational knowledge, to the desired level of using technology for communication, problem solving, and decision making. Staff members will need to make these progressions themselves before they will be able to help students do the same. Professional development is the means to make this happen. Not only should school leaders make staff development available, they can also help these changes occur by modeling appropriate use of technology themselves (Anderson & Dexter, 2005).

Resource acquisition and alignment were identified as indicators of effective school leaders by Leithwood and Riehl (2003), and these skills are also important for school technology leaders. Bosco (2003) states that “creative leadership can find ways around the limitations of funding” (p. 18). I don’t sense an impending Golden Age for education where we have abundant money and time, so school leaders need to find ways to advocate and acquire needed resources for their students and staff.

The ability to develop community and collaborative efforts are key skills for school leaders (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003), and is also identified as a needed competency for effective technology leadership (Flanagan & Jacobsen, 2003). Building community and involving a variety of stakeholders can help secure resources, but these are also essential steps for understanding the variety of needs within a school community. Having this understanding will enable school leaders to address the digital divide found among students of different backgrounds.

Anderson and Dexter (2003) suggest that more research is needed to see how technology leadership fits with general school leadership. Their work found that there were lower levels of technology leadership in the elementary schools, and I’m curious to know why that is. Bosco (2003) shares “The strongest objection to ICT in schools is ideological not empirical” (p. 17). This statement leads me to think about the importance of political and persuasive skills for school leaders. Bosco (2003) also suggests that future research should investigate how technology can lead to more instructional time in addition to how it might effect student engagement. I also wonder about links between principal evaluation data and technology use in schools. In this era of increased educator and school accountability, educator evaluation processes across the country are starting to utilize more quantitative data, rooted in student achievement, to evaluate teachers and principals. It would be interesting to look at this numeric data in comparison to technology implementation.

Anderson, R.E. & Dexter, S. (2005, February). School technology leadership: An empirical investigation of prevalence and effect. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41, (1), 49-82.

Bosco, J. (2003, February). Toward a balanced appraisal of educational technology in U.S. schools and a recognition of seven leadership challenges. Paper presented at the Annual K-12 School Networking Conference of the Consortium for School Networking, Arlington, VA.

Flanagan, L. & Jacobsen, M. (2003). Technology leadership for the twenty-first century principal. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(2), 124-142.

Leithwood, K.A. & Riehl, C. (2003, January). What We Know about Successful School Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.dcbsimpson.com/randd-leithwood-successful-leadership.pdf

A+ Schools Infuse Arts and Other ‘Essentials’ (Edweek repost)

A+ Schools Infuse Arts and Other ‘Essentials’

This is a great article that speaks to the fact that we all need to explore our creative side.

As a group of Oklahoma principals toured Millwood Arts Academy on a recent morning, they snapped photos of student work displayed in hallways, stepped briefly into classrooms, queried the school’s leader, and compared notes.

They were gathered here to observe firsthand a public magnet school that’s seen as a leading example of the educational approach espoused by the Oklahoma A+ Schools network, which has grown from 14 schools a decade ago to nearly 70 today.

A key ingredient, and perhaps the best-known feature, is the network’s strong emphasis on the arts, both in their own right and infused across the curriculum.

“I took a million pictures today and emailed them to all my teachers,” said Principal Leah J. Anderson of Gatewood Elementary School, also in Oklahoma City.

Ms. Anderson said she was struck by the diverse ways students demonstrate their learning, such as a visual representation of the food chain displayed in one hallway.

“It’s not just a page out of the textbook,” she said. “They created it themselves.”

The Oklahoma network has drawn national attention, including praise from U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and mention in a 2011 arts education report from the President’s Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

The A+ approach was not born in Oklahoma, however. It was imported from North Carolina, which launched the first A+ network in 1995 and currently has 40 active member schools. It has since expanded not only to Oklahoma but also to Arkansas, which now counts about a dozen A+ schools. Advocates are gearing up to start a Louisiana network.

Schools participating in the A+ network in Oklahoma and other states commit to a set of eight A+ essentials.

Arts

Taught daily. Inclusive of drama, dance, music, visual arts, and writing. Integrated across curriculum. Valued as “essential to learning.”

Curriculum

Curriculum mapping reflects alignment. Development of “essential questions.” Create and use interdisciplinary thematic units. Cross-curricular integration.

Experiential Learning

Grounded in arts-based instruction. A creative process. Includes differentiated instruction. Provides multifaceted assessment opportunities.

Multiple Intelligences

Multiple-learning pathways used within planning and assessment. Understood by students and parents. Used to create “balanced learning opportunities.”

Enriched Assessment

Ongoing. Designed for learning. Used as documentation. A “reflective” practice. Helps meet school system requirements. Used by teachers and students to self-assess.

Collaboration

Intentional. Occurs within and outside school. Involves all teachers (including arts teachers), as well as students, families, and community. Features “broad-based leadership.”

Infrastructure

Supports A+ philosophy by addressing logistics such as schedules that support planning time. Provides appropriate space for arts. Creates a “shared vision.” Provides professional development. Continual “team building.”

Climate

Teachers “can manage the arts in their classrooms.” Stress is reduced. Teachers treated as professionals. Morale improves. Excitement about the program grows.

The networks are guided by eight core principles, or “essentials,” as they’re called, including a heavy dose of the arts, teacher collaboration, experiential learning, and exploration of “multiple intelligences” among students. At the same time, each state has some differences in emphasis.

Oklahoma’s network describes its mission as “nurturing creativity in every learner.”

The nearly 20 educators who toured Millwood Academy this month—part of a larger group attending a leadership retreat for the state network—covered the gamut from those brand new to the A+ approach to others with years of experience.

“The continual plea from people seeking to do things like this is, ‘Show me, demonstrate,’ ” said Jean Hendrickson, the executive director of Oklahoma A+ Schools, which is part of the University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond.

“[This] is one of the handful of A+ schools we can count on to actively, any day of the week, demonstrate this model in action,” she said at Millwood. “What we want is for the others in our network to have their feet on the ground in a place like this.”

The network faces continual challenges, such as attracting sufficient state aid and coping with the inevitable turnover of school staff, which can strain the degree of fidelity to the A+ essentials.

This fall, 16 member schools in Oklahoma have new principals, more turnover than ever. Some of them lack prior experience with A+, including Consuela M. Franklin, who just took the reins at Owen Elementary School in Tulsa.

“I inherited an A+ school, and so my quest today is to actually learn more, the overall philosophy,” she said. “What it looks like. What it sounds like. How do you know it when you see it?”

Desire to Change

The Oklahoma A+ network has a diverse mix of schools in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Some serve predominantly low-income families. Most are public, though a few are private. And they include traditional public schools, as well as magnets and charters.

The network is supported by both public and private dollars, with all professional development and other supports free to participating schools. But state funding was cut back sharply during the recent economic downturn. An annual line item in the state budget for the network that at its height provided $670,000 was zeroed out in 2011. In the latest budget, it was restored, but only at $125,000.

Schools are drawn to A+ for diverse reasons, said Ms. Hendrickson, who was a principal for 17 years before becoming the network’s leader. But it all boils down to one thing: a desire to change.

“What they want to change ranges broadly,” she said. “It can be they want better test scores. It could be richer activity-based, project-based-learning ideas. It could be taking their success to the next level. It could be more arts.”

As part of the application process, a school must gain the support of 85 percent or more of its faculty members before a review by A+ staff and outside experts. The review is focused mainly on gauging the school’s commitment and capacity to effectively implement the A+ essentials.

The level of fidelity to the approach varies across schools, Ms. Hendrickson said, adding that even within the same school, it may shift over time. “Schools are not static places,” she said.

“Over time, [A+ schools] tend toward one end or the other of our engagement spectrum, whether the informational end, ‘Thank you, we got what we wanted,’ or the transformational end, where, ‘It drives what we do,’ ” she said. “So we have different levels of engagement and different categories of affiliation.”

One teacher at the A+ retreat confided that with a recent leadership switch at her school, the commitment level has declined.

“It’s not the same if you don’t have a leader who is completely active and passionate about it,” she said. “So it has changed, but we’re hanging in there.”

The tightest alignment comes with “demonstration schools.” Those schools, including Millwood Arts Academy, have “made a really strong commitment to the eight A+ essentials, and they are our best partners to help others see what it looks like,” said Ms. Hendrickson.

Millwood is a grades 3-8 magnet that primarily serves African-American students from low-income families. Unlike most Oklahoma A+ schools, it has selective admissions criteria. Admission decisions primarily are reflective of strong student interest in the arts and parents’ embrace of the school’s philosophy, said Christine Harrison, the principal of both that school and Millwood Freshman Academy, which is in the same building and is also an A+ school.

Speaking to her visitors this month, who saw classes for both academies, she sang the praises of the network: “A+ is our driving force.”

Ms. Harrison, who describes her schools as “dripping in the arts,” also emphasized the power of the other A+ essentials, including the intentional collaboration.

“We have teachers collaborating without me having to say ‘collaborate,’ ” she said. “You cannot be isolated in an A+ school.”

‘Shared Experience’

Following the trip to Millwood, the visiting educators spent time sharing ideas and exploring best practices. At one point, the principals sat down in small groups for an intensive, problem-solving exercise. Each leader identified a particular challenge and worked on strategies to cope.

“We provide ongoing professional development and networking opportunities, with a strong research eye on the methods we’re using, the outcomes we’re getting,” said Ms. Hendrickson.

Sandra L. Kent, the principal of Jane Phillips Elementary in Bartlesville, Okla., gives high marks to the professional development, especially the five-day workshop for schools first joining.

“We had a really powerful shared experience,” she said. “That’s one thing, as an A+ school, when you all go and live together for a week.”

Ms. Kent said A+ is often misunderstood as being an “arts program.” The arts dimension gets significant attention “because not a lot of other people talk about it as being so important.” But other elements are also important, she said, such as the call for collaboration and the pursuit of multiple learning pathways that attend to students’ “multiple intelligences.”

Another ingredient is enriched assessment strategies that aim to better capture what students know and are able to do.

One aspect that has helped get A+ schools noticed is the research base.

“They have a very strong evaluation component,” said Sandra S. Ruppert, the executive director of the Washington-based Arts Education Partnership. “They have made the investments, documented their strategies. They can look at the correlation with test scores, but also a whole host of other outcomes. … It is what gives that work greater credibility.”

Both the North Carolina and Oklahoma networks have been the subject of extensive study.

In 2010, Oklahoma A+ Schools issued a five-volume report on data collected by researchers from 2002 to 2007. It found that participating schools, on average, “consistently outperform their counterparts within their district and state on the [Oklahoma] Academic Performance Index,” a measure that relies heavily on student-achievement data.

The study also found other benefits, including better student attendance, decreased disciplinary problems, and more parent and community engagement. But it found the level of fidelity to the A+ essentials uneven, with those schools that adhered most closely seeing the strongest outcomes.

Meanwhile, a separate, more limited study in Oklahoma City compared achievement among students in A+ schools with a matched cohort of students. It found that, on average, students across the seven A+ schools “significantly outperformed” a comparable group of district peers in reading and math, based on 2005 test data. However, not all individual schools outperformed the average, and the study did not measure growth in student achievement over time.

Tapping Into Creativity

Amid growing interest in A+, neighboring Arkansas is ramping up its network, after stalling for a few years. Just recently, several charter schools in the high-profile KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program) network signed on.

“People think KIPP: structure, discipline, rigor. Arts infusion? What the heck do they have in common?” said Scott A. Shirey, the executive director of KIPP Delta Public Schools, which runs schools in Helena and Blytheville, Ark. “But I think it was what we needed to bring our schools to the next level, … to tap into the creativity of teachers and students.”

Mr. Shirey said he values the ongoing support in the A+ network.

“It’s not, ‘We’ll train you for one week, and you’re done,’ ” he said.

Back in Oklahoma, Ms. Kent, the elementary principal, welcomed the fall leadership retreat as a way to get “refreshed and renewed and refocused.”

She said it can be tough to maintain support for an arts-infused approach as schools face the pressure for improved test scores and other demands. In Oklahoma, recent changes include a new teacher-evaluation system, new letter grades for schools, the advent of the Common Core State Standards, and a new 3rd grade retention policy for struggling readers.

“Yes, it’s very difficult with the policy changes to get other people to trust you and trust the [A+] process,” said Ms. Kent, who previously led another A+ school. Her current school is in its second year of transitioning to the A+ essentials.

“Until you really produce the results, people have a hard time going there,” she said.

But Ms. Kent said she’s convinced her school’s journey as part of the network will serve students well.

Schools can’t escape the push for strong test scores, said Ms. Harrison from Millwood Arts Academy. “Let’s face it, that’s a big part of how we’re graded,” she told the visiting educators. “But the A+ Schools way helps you look good on that paper.”

The tour of Millwood was eye-opening for Ms. Franklin, the new principal at Owen Elementary, who came away impressed by this example of A+ in action. She said “evidence was everywhere” of student engagement and learning.

“It was colorful, it was lively, it was audible,” she said. “I am motivated to take it back to my school.”