Learning to “Learn” from Failure….

Yesterday’s post on Education Unbound focused on how teachers can better support student learning by embracing, encouraging and supporting failure in the classroom. This might seem shocking to students who don’t want their instructors to be rooting for them to fail, but we are not talking about catastrophic, epic failure, but rather the kinds of small setbacks that encourage learning. What does that mean and how can you, as a student “fail” and still be successful in your educational goals?

Learning from Your Mistakes

We all make mistakes. I once decided that I would be better served by writing on an exam that the professor’s questions about the history of Native American cultures were irrelevant and proceeded to write a long treatise on the current state of indigenous affairs in the U.S. The “D” I received on that exam is a fair indication that I made a rather significant mistake. But did I learn from my mistake? Absolutely. I learned to play the education game a little better, and I learned that I have a passion for Native American affairs that I hadn’t previously realized. I later turned much of the content of that essay into a portion of a course on “Toxic Literacies” that I taught to incoming freshman.

That was, however, a hard-on-the-GPA lesson to learn. I am not advocating radical/stupid failure just to make a point, but rather acknowledging that you will make mistakes and that you should consciously learn from them. When you find yourself on the wrong side of success in the classroom, what should you do to remedy the situation and turn it to your advantage? Here are some strategies for ensuring that your failures make you a success.

Embrace Metacognition

Metacognition is the process of thinking about your thinking. That may sound convoluted, but it makes sense if you take a step back and think about it for a moment. Rather than just accept that you got something wrong, think about why you got it wrong. Take an academic failure for example and ask yourself these questions:

- Was this a mistake you make repeatedly? If so, is that due to some knowledge or information deficiency you have, that you might be able to remedy?

- Did you get it wrong because it is the first time you have ever seen a problem like this? Would practice with similar problems or tasks help build the skills you need?

- Did you not make a serious effort to solve the problem, complete the assignment, or study the material? If not, why not? Be honest with yourself. That is the only way to really uncover why the failure happened.

- Was there a problem with the test, task, or problem that confused you or made the process of succeeding unnecessarily difficult? If so, do you understand the underlying concepts or skills and can you demonstrate them on other tasks?

Thinking clearly and honestly about why you failed at something is the first step in learning from it. If you are unwilling to take a good hard look at your own actions and culpability in your failure, you are unlikely to learn from it. Avoid the temptation to blame others for your shortcomings, you can’t control them, but you can do things to make yourself better. Once you have examined why you think you failed, you are ready to take the next step in learning from the experience – ask the professor for help.

Ask for Help

Contrary to what some students believe, faculty members are there to help you learn. Not just in the lecture hall or lab, but in their offices, the academic quad, or campus coffee shops. More importantly, they want to help you learn. Most of them sit in their office hours and rarely see any students except the ones who are already doing well in their classes. The ones they want to see, however, are the ones who need their help the most.

Once you have a handle on why you are having problems in a class, and if those problems can be overcome by gaining additional clarification from the instructor, or through some focused tutoring on the topic. Contact the professor to schedule an appointment to talk about yourdeficiencies and how he or she can help you overcome them. It is important to realize that, regardless of any perceived lack of clarity on the part of the faculty member, it is your job to learn the material and succeed. Do not blame them for your failure, regardless of what you think the cause may be.

Ask well-targeted questions that help you address the specific issues that you addressed when you thought through your reasons for failing. Talk about studying strategies, alternative sources for the course information, tutoring, or ask for help filling in gaps in your knowledge. Remember, the professor is there to help you, and you should be thankful for their time and consideration. By doing this you are not only getting help with the immediate problem, but also learning how to become and independent learner who seeks help and interacts with those who can assist them. This is also an excellent way to establish a relationship with faculty members who you may consider asking for professional references in the future.

Explore Alternative Paths to Success

This is the one unconventional piece of advice in this post. If you realize that you are having problems because of a failure to make a concerted effort, or because you are having problems understanding core concepts, and asking the instructor for assistance has not helped or isn’t working, consider going outside the normal channels for assistance.

One realistic possibility is that you might have a specific problem learning some types of information. You might consider visiting your student support services office if you are encountering problems with a specific type of learning. They can help diagnose your particular disability and suggest ways of being successful with it.

If you feel that the presentation of the information simply is not a good match for the way you learn best, consider other sources of learning. There is a wealth of information available online and you can find an alternative presentation of almost any course content in online texts, videos, or even interactive tutorials. You just have to look.

The truly radical option here is to step way outside of the box and craft an alternative way to demonstrate your understanding to the faculty member. If you are constantly failing at writing papers for a class but love to make movies, ask the instructor if you can create a short film in place of the final paper. Perhaps a computer animation of the motion of molecules in a particular atom might be an acceptable outcome in a science class? You will never know if some alternative assessment might be possible if you don’t ask. Worst case is they will say “no” and you are back where you started. Best case is that they say “yes,” you wow the professor with what you show them and they see you as a motivated, creative individual whom they are happy to support in future endeavors.

Failing to Learn is the Only Real Failure

All of these suggestions are predicated on one thing – you need to accept failure as a positive experience that helps you grow. If you can examine your shortcomings with some objectivity, you will begin to position yourself to not only overcome them, but to develop lifelong habits of addressing your failings that will make you much more successful in the long run. As Dale Carnegie once said, “Develop success from failures. Discouragement and failure are two of the surest stepping stones to success.”

Numbers Can Lie: What TIMSS and PISA Truly Tell Us, if Anything?

“America’s Woeful Public Schools: TIMSS Sheds Light on the Need for Systemic Reform”[1]

“Competitors Still Beat U.S. in Tests”[2]

“U.S. students continue to trail Asian students in math, reading, science”[3]

These are a few of the thousands of headlines generated by the release of the 2011 TIMSS and PIRLS results today. Although the results are hardly surprising or news worthy, judging from the headlines, we can expect another global wave of handwringing, soul searching, and calls for reform. But before we do, we should ask how meaningful these scores and rankings are.

“Numbers don’t lie,” many may say but what truth do they tell? Look at the following numbers:

Table 1: Scores and Attitudes of 8th Graders in TIMSS 2011

| Country | Math Scores | Confidence (%) (4th Grade) | Value Math (%) |

| Korea | 613 | 03 (11) | 14 |

| Singapore | 611 | 14 (21) | 43 |

| Chinese Taipei | 609 | 07 (20) | 13 |

| Hong Kong | 586 | 07 (24) | 26 |

| Japan | 570 | 02 (09) | 13 |

| United States | 509 | 24 (40) | 51 |

| England | 507 | 16 (33) | 48 |

| Australia | 505 | 17 (38) | 46 |

These are the scores of 8th graders and percentage of them saying they are confident in math and value math. Top scoring Korea has only 3% of students feeling confident in their math and 14% valuing math, in contrast is Australia with much lower scores but significantly higher percentage of students feeling confident in math and valuing math. In fact, the top 5 East Asian countries in math scores have way fewer students reporting confidence in math and valuing math than the U.S., England, and Australia, all scored significantly lower.

It gives me a headache to understand these numbers: Do they mean that even if the Korean students do not think math is important, they study it anyway? and they have a very effective education that can make people who do not value math to be outstanding in it? Or since these are 8th graders, do they mean that after learning math for 8 years, the students feel the math they have been learning is not important in life? In the case of the United States, do they mean that American students value math but have poor math learning experiences that lead to low math achievement? Or could it be that their 8 years of math learning convinced them, at least a much larger proportion than in Korea, that math is important?

The same questions can be asked about confidence. Do the numbers mean that Korean students lack of confidence makes them study harder so they achieve better in math than their American or Australian counterparts? Or could they mean that the way math is taught in Korea made them lose confidence in math?

The data show that as students progress toward higher grades, they become less confident in their math learning. More fourth graders than eighth graders have confidence in math, for example. Does this mean the more they learn, the less confident they become?

Or perhaps these numbers are not related at all. But the TIMSS report suggests that within countries students with higher scores are more likely to have a more positive attitude towards math, that is, a positive correlation. A negative correlation is found between countries and has been a pattern as Tom Loveless discovered in previous TIMSS. So somehow math scores, attitudes, and confidence are related. Perhaps whatever in an education system or culture that boosts math scores leads to less positive attitude and lower confidence at the same time. In this case, one needs to ask what is more important: scores, or confidence and positive attitude?

There can be other interpretations but whatever the interpretation is, these numbers show that results of TIMSS, or other international assessments such as the PISA, are a lot more complex than what the headlines attempt to suggest: Asians are great, America sucks, so do Australia and England. The TIMSS and PISA scores are perhaps worth much less than politicians and the media make of them, as the rest of this paper shows.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: A Long History of Bad Performance on International Tests

According to historical data, American education has always been bad and actually improving over the years. In the 1960s, when the First International Mathematics Study (FIMS) and the First International Science Study (FISS)[4] was conducted, U.S. students ranked bottom in virtually all categories:

11th out of 12 (8th grade -13 year old math)

12th out 12 (12th grade math for math students)

10th out 12 (12th grade math for non-math students)

7th out 19 (14 year-old science)

14th out of 19 (12th grade science)

In the 1980s, when the Second International Mathematics Study (SIMS) and Second International Science Study (SISS)[5] were conducted, U.S. students inched up a little bit, but not much:

10th out of 20 (8th grade-Arithmetic)

12th out of 20 (8th grade-Algebra)

16th out of 20 (8th grade-Geometry)

18th out of 20 (8th grade-Measurement)

8th out of 20 (8th grade-Statistics)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Number Systems)

14th out of 15 (12th grade-Algebra)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Geometry)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Calculus)

14th out of 17 (14 year-old Science)

14th out of 14 (12th grade-Biology)

122h out of 14 (12th grade-Chemistry)

10th out of 14 (12th grade-Physics)

In the 1990s, in the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)[6], American test performance was not the best but again improved:

28th out 41 (but only 20 countries performed significantly better) (8th grade math)

17th out 41 (but only 9 countries performed significantly better) (8th grade science)

In 2003, in TIMSS[7] (now changed into Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), U.S. students were not great, but again improved:

15th out of 45 (only 9 countries significantly better) (8th grade math)

9th out of 45 (only 7 countries significantly better) (8th grade science)

In 2007, U.S. improved again in TIMMS[8], although still not the top ranking country:

9th out of 47 (only 5 countries significant better) (8th grade math)

10th out of 47 (only 8 countries significantly better) (8th grade science)

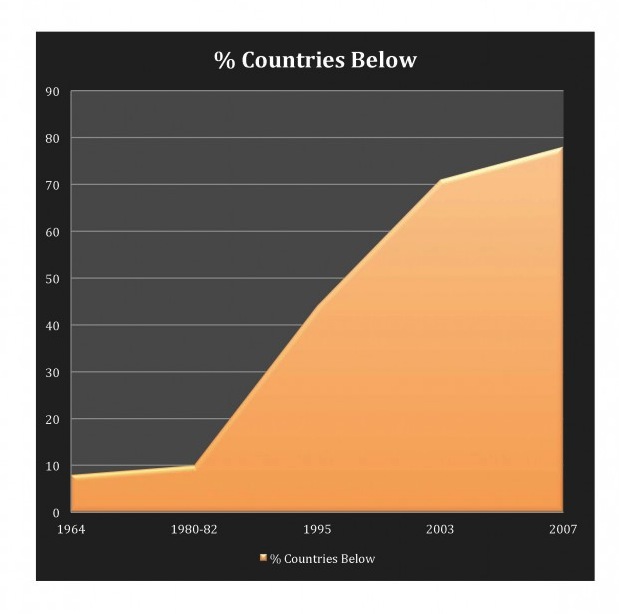

Over the half century, American students performance in international math and science tests has improved from the bottom to above international average. The following figure shows the upward trend of American students’ performance in math. Because 8th grade seems to be the only group that has been tested every time since the 1960s, the graph only includes data for 8th grade math[9].

All the studies mentioned above have been coordinated by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). There is another international study, one that has gained more momentum and popularity than the ones organized by IEA. This is the Programme for International Student Assessment, better known as PISA, organized by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA was first introduced in 2000 and tests 15 year olds in math, literacy, and science. It is conducted every three years. Because PISA is fairly new, so there is not a clear trend to show whether the U.S. is doing better or worse, but it is clear that U.S. students are not among the best[10]:

PISA Reading Literacy

15th out of 30 countries in 2000

17th out of 77 countries in 2009

PISA Math

24th out of 29 countries in 2003

31st out of 74 countries in 2009

PISA Sciences

21st out of 30 countries in 2003

23rd out of 74 countries in 2009

There are other studies and statistics, but this long list should be sufficient to prove that American students have been awful test takers for over half a century. Some has taken this mean American education has been awful in comparison to others. This interpretation has been common and backed up by media reports, scholarly books, and documentary films, for example:

1950s-1960s: Worse than the Soviet Union (1958, Life Magazine cover story Crisis in Education)[11]

1980s-1990s: Worse than Japan and others (A Nation at Risk[12], Learning Gap: Why Our Schools Are Failing And What We Can Learn From Japanese And Chinese Education[13])

2000s–: Worse than China and India (2 Million Minutes[14] (documentary film) Surpassing Shanghai)[15]

The Numbers Don’t Lie, but What Truth Do They Tell

Numbers can be used to tell stories of the past or the future. We can ask how we arrived at a certain number or what it means for the future. Asking about its past invites us to consider what we did or did not do to achieve a certain state indicated by the number. Asking about its future implications forces us to question if a certain number is desirable or meaningful. The latter must precede the former because unless the state measured by certain numbers has truly significant implications for a desirable future, the question about how we got there is practically a waste of time.

In the case of statistics from international educational assessments, the question about the future has rarely been explored. It has been assumed that these numbers indicate nations’ capacity to build a better future. And thus we must dive in urgently to learn about why others are getting better numbers than us. This assumption, however, may be wrong.

The Numbers’ Future

“Our future depends on the strength of our education system. But that system is crumbling,” reads a full-page ad in the New York Times. Dominating the ad is a graphic that shows “national security,” “jobs,” and the “economy” resting upon a cracking base of education. This ad is part of the “innovative, multitactical” Don’t Forget Ed campaign the College Board sponsored.

It is apparent America’s national security, jobs, and economy has been resting upon a base that has been crumbling and cracking for over half a century, according to the numbers. So one would logically expect the U.S. to have fallen through the cracks and hit rock bottom in national security, jobs, and economy by now. But facts seem to suggest otherwise:

The Soviet Union, America’s archrival in national security during the Cold War, which supposedly had better education than the U.S., disappeared and the U.S. remains the dominant military power in the world.

Japan, which was expected to take over the U.S. because of its superior education in the 1980s, has lost its #2 status in terms of size of economy. Its GDP is about 1/3 of America’s. Its per capita GDP is about $10,000 less than that in the U.S.

The U.S. is the 6th wealthiest country in the world in 2011 in terms of per capita GDP[16]. It is still the largest economy in the world.

The U.S. ranked 5th out of 142 countries in Global Competitiveness in 2012 and 4th in 2011[17].

The U.S. ranked 2nd out 82 countries in Global Creativity, behind only Sweden[18] in 2011.

The U.S. ranked 1st in the number of patents filled or granted by major international patent offices in 2008, with 14,399 filings, compared to 473 filings from China[19], which supposedly has a superior education[20].

Obviously America’s poor education told by the numbers has not ruined its national security and economy. These numbers have failed to tell the story of the future.

The Numbers’ Past

The past stories of numbers lie the lessons to be learned. The problem is that there are different ways to achieve the same number, although a set of factors have been identified to explain why American students perform worse than other countries or what made some other countries achieve better numbers. As a result, the most of the factors become debatable and debated myths, half-truths, or “duh!”

Time. American students spend less time studying. President Obama noted that on average U.S. students attend class about a month less than children in other advanced countries[21] in 2010. His Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said students in China and India attend school 25 to 30 percent longer than in the U.S.[22] A 1994 report of the National Education Commission on Time and Learning established by U.S. Congress observed “Students in other post-industrial democracies receive twice as much instruction in core academic areas during high school.”[23] However a study by the Center for Public Education says “students in China and India are not required to spend more time in school than most U.S. students.”[24]

Engagement and Commitment. American students, schools, parents, and governments don’t take school-based learning as seriously as other top performing countries. Not only students in other countries spend more time in school, “the formidable learning advantage Japanese and German schools provide to their students is complemented by equally impressive out-of-school learning,” noted the National Education Commission on Time and Learning in 1994[25]. “Compared with other societies, young people in Shanghai may be much more immersed in learning in the broadest sense of the term. The logical conclusion is that they learn more…” writes an OECD report explaining Shanghai’s outstanding PISA scores[26]. But the same report immediately notes “what they learn and how they learn are subjects of constant debate.”

Curriculum, Standards, Gateways, and Tests. The U.S. does not have a better (more focus, rigor, and coherence) common curriculum with high standards across the nation and an instructional system with clearly marked transition points. “…standards in the best-performing nations share the following three characteristics [focus, rigor, and coherence] that are not commonly found in U.S. standards,” says a report that calls for international benchmarking by the National Governors’ Association[27]. “Virtually all high-performing countries have a system of gateways marking the key transition points…At each of these major gateways, there is some form of external national assessment,” writes Marc Tucker in Surpassing Shanghai: An Agenda for American Education Built on the World’s Leading Systems (Tucker, 2011, p. 174). But Ontario, a top PISA performer does not, admits Tucker and schools in Finland, a much admired high performer on the PISA, “is a “standardized testing-free zone,”[28] writes Diane Ravitch.

Teachers and Teacher Education. American teachers are not as smart to begin with and are less well prepared than their counterparts in high performing countries. For example, while 100% of teachers in top performing countries –Singapore, Finland and South Korea — are recruited form the top third college graduates, only 23% are from the top third in the U.S., according to a study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Co[29]. Teachers in these top performing countries are also better trained, supported, and motivated before, during, and after taking the teaching job. This is one of the “duhs.”

Inequity and poverty. There is more social economic disparity among U.S. students and higher levels of poverty in the U.S. than other countries. “U.S. students in schools with 10% or less poverty are number one country in the world,” says a report of the National Association of Secondary School Principals[30]. The report establishes a direct connection between PISA performance and poverty and says the U.S. has the largest number of students living in poverty. But others disagree. “The U.S. looks about average compared with other wealthy nations on most measures of family background,” says the report from the National Governor’s Association, “Moreover, America’s most affluent15-year-olds ranked only 23rd in math and 17th in science on the 2006 PISA assessment when compared with affluent students in other industrialized nations.”[31]

There are of course other suggestions from access to natural resources[32] to cultural homogeneity and from sampling bias to parenting styles. Regardless, how each country achieved their international scores is not nearly as straightforward as the numbers themselves, making international learning a very difficult task.

The task becomes perhaps even more difficult, when the issues of economic, cultural, societal, and political contexts are considered. What’s more, learning from others may become not so desirable for the U.S. considering the fact that the test scores have not significantly affected America’s national security and economy. Moreover in the final analysis, since countries that have shown better numbers in tests have not performed necessarily better than the U.S., the U.S. education may have something to offer others.

The Numbers Don’t Lie, but Some Are Missing: Two Paradigms of Education

The fact the U.S. as a nation is still standing despite of its abysmal standing on international academic tests for over half a century begs two questions:

Is education as important to a nation’s national security and economy as important as believed?

If it is, are the numbers telling the truth about the quality of education in the U.S. and other nations?

If the answer to the first question is “no,” we need to disconnect the automatic association between test scores and education. In other words, the numbers don’t really measure education, at least not the entire picture of the education needed to produce citizens to build strong and prosperous economies.

In my latest book World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students[33], I identified two paradigms of education: employee-oriented and entrepreneur-oriented. The employee-oriented paradigm aims to transmit a prescribed set of content (the curriculum and standards) deemed to be useful for future life by external authorities, while the entrepreneur-oriented aims to cultivate individual talents and enhance individual strengths. The employee-oriented paradigm produces homogenous, compliant, and standardized workers for mass employment while the entrepreneurial-oriented education encourages individuality, diversity, and creativity.

Although in general, all mainstream education systems in the world currently follows the employee-oriented paradigm, some may not be as effectively and successfully as others. The international test scores may be an indicator of how successful and effective the employee-oriented education has been executed. In other words, these numbers are measures of how successful the prescribed content has been transmitted to all students. But the prescribed content does not have much to do with an already industrialized country such as the U.S., whose economy relies on innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship. As a result, although American schools have not been as effective and successful in transmitting knowledge as the test scores indicate, they have somehow produced more creative entrepreneurs, who have kept the country’s economy going. Moreover, it is possible that on the way to produce those high test scores, other education systems may have discouraged the cultivation of the creative and entrepreneurial spirit and capacity.

Unfortunately there are few numbers that directly provide the same kind of comparison as TIMSS and PISA on measures of creativity and entrepreneurship, making it difficult to forcefully prove that American education indeed produce more creative and entrepreneurial talents. A piece of data I have found from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor study suggests a significant negative relationship between PISA performance and indicators of entrepreneurship. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, or GEM, is an annual assessment of entrepreneurial activities, aspirations, and attitudes of individuals in more than 50 countries. Initiated in 1999, about the same time that PISA began, GEM has become the world’s largest entrepreneurship study. Thirty-nine countries that participated in the 2011 GEM also participated in the 2009 PISA, and 23 out of the 54 countries in GEM are considered “innovation-driven” economies, which means developed countries.

Comparing the two sets of data shows clearly countries that score high on PISA do not have levels of entrepreneurship that match their stellar scores. More importantly, it seems that countries with higher PISA scores have fewer people confident in their entrepreneurial capabilities. Out of the innovation-driven economies, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan are among the best PISA performers, but their scores on the measure of perceived capabilities or confidence in one’s ability to start a new business are the lowest. The correlation coefficients between scores on the 2009 PISA in math, reading, and science and 2011 GEM in “perceived entrepreneurial capability” in the 23 developed countries are all statistically significant[34].

Anecdotally, Vivek Wadhwa, president of Academics and Innovation at Singularity University, Fellow at Stanford Law School and Director of Research at Pratt School of Engineering at Duke University, wrote in Business Week in response to the latest PISA rankings:

The independence and social skills American children develop give them a huge advantage when they join the workforce. They learn to experiment, challenge norms, and take risks. They can think for themselves, and they can innovate. This is why America remains the world leader in innovation; why Chinese and Indians invest their life savings to send their children to expensive U.S. schools when they can. India and China are changing, and as the next generations of students become like American ones, they too are beginning to innovate. So far, their education systems have held them back.[35]

But there again are no numbers to prove these. However, other countries, particularly the high scoring Asian countries have all been reforming their education systems to be more like that in the U.S., as I have discussed in my book Catching Up or Leading the Way: American Education in the Age of Globalization[36].

Conclusions

I have put forth a lot of numbers of different sorts from a variety of sources. Taken together, these numbers suggest to me the following:

So far all international test scores measure the extent to which an education system effectively transmits prescribed content.

In this regard, the U.S. education system is a failure and has been one for a long time.

But the successful transmission of prescribed content contributes little to economies that require creative and entrepreneurial individual talents and in fact can damage the creative and entrepreneurial spirit. Thus high test scores of a nation can come at the cost of entrepreneurial and creative capacity.

While the U.S. has failed to produce homogenous, compliant, and standardized employees, it has preserved a certain level of creativity and entrepreneurship. In other words, while the U.S. is still pursuing an employee-oriented education model, it is much less successful in stifling creativity and suppressing entrepreneurship.

The U.S. success in creativity and entrepreneurship is merely an accidental by product of a less successful employee-oriented education, which is far from sufficient to meet the coming challenges brought about by globalization and technological changes. Thus in a sense, the U.S. education is in turmoil, inadequate, and obsolete, but it has to move toward more entrepreneur-oriented instead of more employee-oriented.

[1] http://dropoutnation.net/2012/12/11/americas-woeful-public-schools-timms-sheds-light-on-the-need-for-systemic-reform/

[2] http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324339204578171753215198868.html

[3] http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/us-students-continue-to-trail-asian-students-in-math-reading-science/2012/12/10/4c95be68-40b9-11e2-ae43-cf491b837f7b_story.html

[4] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs92/92011.pdf

[5] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs92/92011.pdf

[6] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs99/1999081.pdf

[7] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results03.asp

[8] http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results07.asp

[9] Since SIMS scores were reported in sub domains, I chose the lowest performance area for the U.S. students: Measurement.

[10] Data source: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/

[11] http://goo.gl/pAgnQ

[12] http://datacenter.spps.org/uploads/SOTW_A_Nation_at_Risk_1983.pdf

[13] http://books.google.com/books/about/Learning_Gap.html?id=HIfBn5W6LMcC

[14] http://www.2mminutes.com/

[15] http://www.amazon.com/Surpassing-Shanghai-American-Education-Leading/dp/1612501036

[16] Data source: International Monetary Fund: http://goo.gl/r7SFQ

[17] http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GCR_Report_2011-12.pdf

[18] Data source: http://www.theatlanticcities.com/jobs-and-economy/2011/10/global-creativity-index/229/

[19] Data Source: Chinese Innovation is a Paper Tiger http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904800304576472034085730262.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

[20] Students from Shanghai China scored 1st on the PISA in all three subjects (math, reading, and sciences) in the last round of PISA released in 2010.

[21] http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/39378576/ns/today-parenting/#.UEPqb2ie7sc

[22] http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Organizing-a-school/Time-in-school-How-does-the-US-compare

[23] http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/PrisonersOfTime/Lessons.html

[24] http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Organizing-a-school/Time-in-school-How-does-the-US-compare

[25] http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/PrisonersOfTime/Lessons.html

[26] http://www.oecd.org/countries/hongkongchina/46581016.pdf

[27] http://www.corestandards.org/assets/0812BENCHMARKING.pdf

[28] http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/mar/08/schools-we-can-envy/?pagination=false

[29] http://mckinseyonsociety.com/closing-the-talent-gap/

[30] http://nasspblogs.org/principaldifference/2010/12/pisa_its_poverty_not_stupid_1.html

[31] http://www.corestandards.org/assets/0812BENCHMARKING.pdf

[32] http://www.oecd.org/education/preschoolandschool/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/49881940.pdf

[33] http://zhaolearning.com/world-class-learners-my-new-book/

[34] http://zhaolearning.com/2012/08/16/doublethink-the-creativity-testing-conflict/

[35] http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/jan2011/tc20110112_006501.htm

[36] http://zhaolearning.com/2009/11/14/3/

This is a repost from the blog of Dr. Yong Zhao.

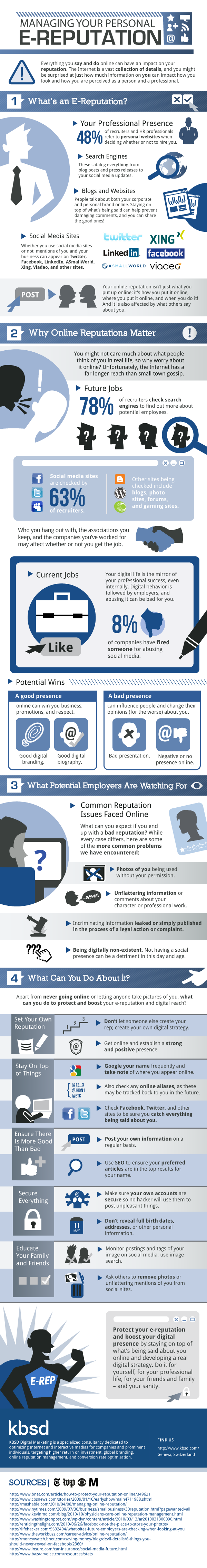

Managing your digital footprint…

“Everything you say and do online can have an impact on your reputation. The Internet is a vast collection of details, and you might be surprised at just how much information on you can impact how you look and how you are perceived as a person and a professional.”

The infographic is split into 4 sections:

- What is an e-reputation?

- Why online reputations matter

- What potential employers are watching for

- What can you do about it?

I’ve included the final section below, but please please look at the previous ones too (click the image for the full infographic) as the information is well presented and well worth a couple of minutes of your time – if for nothing else so you can be sure you’re doing it right.

“Protect your e-reputation and boost your digital presence by staying on top of what’s being said about you online and developing a real digital strategy. Do it for yourself, for your professional life, for your friends and family – and your sanity.”

More thoughts on effective school technology leadership by @WiscPrincipal

After reading this post by @WiscPrincipal I felt it was important to share it with my followers or readers.

Effective school technology implementation does not occur if there is not effective leadership in place to make it happen. It takes a lot of vision, passion, resources, and coordination, vision, to bring technology (or any new resource or practice) into an organization to make a positive impact on learning and teaching. The school leader is the key player in these areas. Leithwood and Riehl (2003) highlight the importance of school leadership by noting that it is second only to instruction from teachers when it comes to impacting student learning.

I’ll echo Todd Hurst’s thoughts that effective school technology leadership does not differ greatly from good school leadership. Leaders set a vision, share the vision, outline expectations, make goals, and then monitor performance toward that vision (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003). The work of Anderson and Baxter (2005) and Flanagan and Jacobsen (2003) also speak to the importance of the leader having a vision about the use of school technology.

The school leader must have a good understanding of best instructional practices and pay attention to their effect on student learning. The use of technology can be considered a best instructional practice, but tech use can’t be “business as usual with computers” (Bosco, 2003; p. 15). Flanagan and Jacobson (2003) share that, “Merely installing computers and networks in schools is insufficient for educational reform” (p. 125). We need to move past the focus on acquisition of resources, and put work into using those resources to have an impact on learning (Bosco, 2003). This type of instructional shift is where leadership really matters.

The provision of staff development has been identified as an important school leadership factor by Leithwood and Riehl (2003), and is also noted as key for the implementation of effective school technology programs. Bosco (2003) shares that professional development is essential for schools to move beyond the mere presence of computers, to effectively using them as a teaching and learning tool. Flanagan and Jacobsen (2003) show how student technology use progresses from productivity, to foundational knowledge, to the desired level of using technology for communication, problem solving, and decision making. Staff members will need to make these progressions themselves before they will be able to help students do the same. Professional development is the means to make this happen. Not only should school leaders make staff development available, they can also help these changes occur by modeling appropriate use of technology themselves (Anderson & Dexter, 2005).

Resource acquisition and alignment were identified as indicators of effective school leaders by Leithwood and Riehl (2003), and these skills are also important for school technology leaders. Bosco (2003) states that “creative leadership can find ways around the limitations of funding” (p. 18). I don’t sense an impending Golden Age for education where we have abundant money and time, so school leaders need to find ways to advocate and acquire needed resources for their students and staff.

The ability to develop community and collaborative efforts are key skills for school leaders (Leithwood & Riehl, 2003), and is also identified as a needed competency for effective technology leadership (Flanagan & Jacobsen, 2003). Building community and involving a variety of stakeholders can help secure resources, but these are also essential steps for understanding the variety of needs within a school community. Having this understanding will enable school leaders to address the digital divide found among students of different backgrounds.

Anderson and Dexter (2003) suggest that more research is needed to see how technology leadership fits with general school leadership. Their work found that there were lower levels of technology leadership in the elementary schools, and I’m curious to know why that is. Bosco (2003) shares “The strongest objection to ICT in schools is ideological not empirical” (p. 17). This statement leads me to think about the importance of political and persuasive skills for school leaders. Bosco (2003) also suggests that future research should investigate how technology can lead to more instructional time in addition to how it might effect student engagement. I also wonder about links between principal evaluation data and technology use in schools. In this era of increased educator and school accountability, educator evaluation processes across the country are starting to utilize more quantitative data, rooted in student achievement, to evaluate teachers and principals. It would be interesting to look at this numeric data in comparison to technology implementation.

Anderson, R.E. & Dexter, S. (2005, February). School technology leadership: An empirical investigation of prevalence and effect. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41, (1), 49-82.

Bosco, J. (2003, February). Toward a balanced appraisal of educational technology in U.S. schools and a recognition of seven leadership challenges. Paper presented at the Annual K-12 School Networking Conference of the Consortium for School Networking, Arlington, VA.

Flanagan, L. & Jacobsen, M. (2003). Technology leadership for the twenty-first century principal. Journal of Educational Administration, 41(2), 124-142.

Leithwood, K.A. & Riehl, C. (2003, January). What We Know about Successful School Leadership. Retrieved from http://www.dcbsimpson.com/randd-leithwood-successful-leadership.pdf

A+ Schools Infuse Arts and Other ‘Essentials’ (Edweek repost)

A+ Schools Infuse Arts and Other ‘Essentials’

This is a great article that speaks to the fact that we all need to explore our creative side.

As a group of Oklahoma principals toured Millwood Arts Academy on a recent morning, they snapped photos of student work displayed in hallways, stepped briefly into classrooms, queried the school’s leader, and compared notes.

They were gathered here to observe firsthand a public magnet school that’s seen as a leading example of the educational approach espoused by the Oklahoma A+ Schools network, which has grown from 14 schools a decade ago to nearly 70 today.

A key ingredient, and perhaps the best-known feature, is the network’s strong emphasis on the arts, both in their own right and infused across the curriculum.

“I took a million pictures today and emailed them to all my teachers,” said Principal Leah J. Anderson of Gatewood Elementary School, also in Oklahoma City.

Ms. Anderson said she was struck by the diverse ways students demonstrate their learning, such as a visual representation of the food chain displayed in one hallway.

“It’s not just a page out of the textbook,” she said. “They created it themselves.”

The Oklahoma network has drawn national attention, including praise from U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and mention in a 2011 arts education report from the President’s Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

The A+ approach was not born in Oklahoma, however. It was imported from North Carolina, which launched the first A+ network in 1995 and currently has 40 active member schools. It has since expanded not only to Oklahoma but also to Arkansas, which now counts about a dozen A+ schools. Advocates are gearing up to start a Louisiana network.

Schools participating in the A+ network in Oklahoma and other states commit to a set of eight A+ essentials.

Arts

Taught daily. Inclusive of drama, dance, music, visual arts, and writing. Integrated across curriculum. Valued as “essential to learning.”

Curriculum

Curriculum mapping reflects alignment. Development of “essential questions.” Create and use interdisciplinary thematic units. Cross-curricular integration.

Experiential Learning

Grounded in arts-based instruction. A creative process. Includes differentiated instruction. Provides multifaceted assessment opportunities.

Multiple Intelligences

Multiple-learning pathways used within planning and assessment. Understood by students and parents. Used to create “balanced learning opportunities.”

Enriched Assessment

Ongoing. Designed for learning. Used as documentation. A “reflective” practice. Helps meet school system requirements. Used by teachers and students to self-assess.

Collaboration

Intentional. Occurs within and outside school. Involves all teachers (including arts teachers), as well as students, families, and community. Features “broad-based leadership.”

Infrastructure

Supports A+ philosophy by addressing logistics such as schedules that support planning time. Provides appropriate space for arts. Creates a “shared vision.” Provides professional development. Continual “team building.”

Climate

Teachers “can manage the arts in their classrooms.” Stress is reduced. Teachers treated as professionals. Morale improves. Excitement about the program grows.

The networks are guided by eight core principles, or “essentials,” as they’re called, including a heavy dose of the arts, teacher collaboration, experiential learning, and exploration of “multiple intelligences” among students. At the same time, each state has some differences in emphasis.

Oklahoma’s network describes its mission as “nurturing creativity in every learner.”

The nearly 20 educators who toured Millwood Academy this month—part of a larger group attending a leadership retreat for the state network—covered the gamut from those brand new to the A+ approach to others with years of experience.

“The continual plea from people seeking to do things like this is, ‘Show me, demonstrate,’ ” said Jean Hendrickson, the executive director of Oklahoma A+ Schools, which is part of the University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond.

“[This] is one of the handful of A+ schools we can count on to actively, any day of the week, demonstrate this model in action,” she said at Millwood. “What we want is for the others in our network to have their feet on the ground in a place like this.”

The network faces continual challenges, such as attracting sufficient state aid and coping with the inevitable turnover of school staff, which can strain the degree of fidelity to the A+ essentials.

This fall, 16 member schools in Oklahoma have new principals, more turnover than ever. Some of them lack prior experience with A+, including Consuela M. Franklin, who just took the reins at Owen Elementary School in Tulsa.

“I inherited an A+ school, and so my quest today is to actually learn more, the overall philosophy,” she said. “What it looks like. What it sounds like. How do you know it when you see it?”

Desire to Change

The Oklahoma A+ network has a diverse mix of schools in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Some serve predominantly low-income families. Most are public, though a few are private. And they include traditional public schools, as well as magnets and charters.

The network is supported by both public and private dollars, with all professional development and other supports free to participating schools. But state funding was cut back sharply during the recent economic downturn. An annual line item in the state budget for the network that at its height provided $670,000 was zeroed out in 2011. In the latest budget, it was restored, but only at $125,000.

Schools are drawn to A+ for diverse reasons, said Ms. Hendrickson, who was a principal for 17 years before becoming the network’s leader. But it all boils down to one thing: a desire to change.

“What they want to change ranges broadly,” she said. “It can be they want better test scores. It could be richer activity-based, project-based-learning ideas. It could be taking their success to the next level. It could be more arts.”

As part of the application process, a school must gain the support of 85 percent or more of its faculty members before a review by A+ staff and outside experts. The review is focused mainly on gauging the school’s commitment and capacity to effectively implement the A+ essentials.

The level of fidelity to the approach varies across schools, Ms. Hendrickson said, adding that even within the same school, it may shift over time. “Schools are not static places,” she said.

“Over time, [A+ schools] tend toward one end or the other of our engagement spectrum, whether the informational end, ‘Thank you, we got what we wanted,’ or the transformational end, where, ‘It drives what we do,’ ” she said. “So we have different levels of engagement and different categories of affiliation.”

One teacher at the A+ retreat confided that with a recent leadership switch at her school, the commitment level has declined.

“It’s not the same if you don’t have a leader who is completely active and passionate about it,” she said. “So it has changed, but we’re hanging in there.”

The tightest alignment comes with “demonstration schools.” Those schools, including Millwood Arts Academy, have “made a really strong commitment to the eight A+ essentials, and they are our best partners to help others see what it looks like,” said Ms. Hendrickson.

Millwood is a grades 3-8 magnet that primarily serves African-American students from low-income families. Unlike most Oklahoma A+ schools, it has selective admissions criteria. Admission decisions primarily are reflective of strong student interest in the arts and parents’ embrace of the school’s philosophy, said Christine Harrison, the principal of both that school and Millwood Freshman Academy, which is in the same building and is also an A+ school.

Speaking to her visitors this month, who saw classes for both academies, she sang the praises of the network: “A+ is our driving force.”

Ms. Harrison, who describes her schools as “dripping in the arts,” also emphasized the power of the other A+ essentials, including the intentional collaboration.

“We have teachers collaborating without me having to say ‘collaborate,’ ” she said. “You cannot be isolated in an A+ school.”

‘Shared Experience’

Following the trip to Millwood, the visiting educators spent time sharing ideas and exploring best practices. At one point, the principals sat down in small groups for an intensive, problem-solving exercise. Each leader identified a particular challenge and worked on strategies to cope.

“We provide ongoing professional development and networking opportunities, with a strong research eye on the methods we’re using, the outcomes we’re getting,” said Ms. Hendrickson.

Sandra L. Kent, the principal of Jane Phillips Elementary in Bartlesville, Okla., gives high marks to the professional development, especially the five-day workshop for schools first joining.

“We had a really powerful shared experience,” she said. “That’s one thing, as an A+ school, when you all go and live together for a week.”

Ms. Kent said A+ is often misunderstood as being an “arts program.” The arts dimension gets significant attention “because not a lot of other people talk about it as being so important.” But other elements are also important, she said, such as the call for collaboration and the pursuit of multiple learning pathways that attend to students’ “multiple intelligences.”

Another ingredient is enriched assessment strategies that aim to better capture what students know and are able to do.

One aspect that has helped get A+ schools noticed is the research base.

“They have a very strong evaluation component,” said Sandra S. Ruppert, the executive director of the Washington-based Arts Education Partnership. “They have made the investments, documented their strategies. They can look at the correlation with test scores, but also a whole host of other outcomes. … It is what gives that work greater credibility.”

Both the North Carolina and Oklahoma networks have been the subject of extensive study.

In 2010, Oklahoma A+ Schools issued a five-volume report on data collected by researchers from 2002 to 2007. It found that participating schools, on average, “consistently outperform their counterparts within their district and state on the [Oklahoma] Academic Performance Index,” a measure that relies heavily on student-achievement data.

The study also found other benefits, including better student attendance, decreased disciplinary problems, and more parent and community engagement. But it found the level of fidelity to the A+ essentials uneven, with those schools that adhered most closely seeing the strongest outcomes.

Meanwhile, a separate, more limited study in Oklahoma City compared achievement among students in A+ schools with a matched cohort of students. It found that, on average, students across the seven A+ schools “significantly outperformed” a comparable group of district peers in reading and math, based on 2005 test data. However, not all individual schools outperformed the average, and the study did not measure growth in student achievement over time.

Tapping Into Creativity

Amid growing interest in A+, neighboring Arkansas is ramping up its network, after stalling for a few years. Just recently, several charter schools in the high-profile KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program) network signed on.

“People think KIPP: structure, discipline, rigor. Arts infusion? What the heck do they have in common?” said Scott A. Shirey, the executive director of KIPP Delta Public Schools, which runs schools in Helena and Blytheville, Ark. “But I think it was what we needed to bring our schools to the next level, … to tap into the creativity of teachers and students.”

Mr. Shirey said he values the ongoing support in the A+ network.

“It’s not, ‘We’ll train you for one week, and you’re done,’ ” he said.

Back in Oklahoma, Ms. Kent, the elementary principal, welcomed the fall leadership retreat as a way to get “refreshed and renewed and refocused.”

She said it can be tough to maintain support for an arts-infused approach as schools face the pressure for improved test scores and other demands. In Oklahoma, recent changes include a new teacher-evaluation system, new letter grades for schools, the advent of the Common Core State Standards, and a new 3rd grade retention policy for struggling readers.

“Yes, it’s very difficult with the policy changes to get other people to trust you and trust the [A+] process,” said Ms. Kent, who previously led another A+ school. Her current school is in its second year of transitioning to the A+ essentials.

“Until you really produce the results, people have a hard time going there,” she said.

But Ms. Kent said she’s convinced her school’s journey as part of the network will serve students well.

Schools can’t escape the push for strong test scores, said Ms. Harrison from Millwood Arts Academy. “Let’s face it, that’s a big part of how we’re graded,” she told the visiting educators. “But the A+ Schools way helps you look good on that paper.”

The tour of Millwood was eye-opening for Ms. Franklin, the new principal at Owen Elementary, who came away impressed by this example of A+ in action. She said “evidence was everywhere” of student engagement and learning.

“It was colorful, it was lively, it was audible,” she said. “I am motivated to take it back to my school.”

Technology in kids’ bedrooms lead to poorer health, study suggests

Many children go to bed with one or more screens in their bedrooms, and doing so is damaging their well-being, according to a new study from the University of Alberta.

“If you want your kids to sleep better and live a healthier lifestyle, get the technology out of the bedroom,” Paul Veugelers, a professor in the school of public health and co-author of the study, said in a release.

Researchers examined data from a survey of nearly 3,400 Grade 5 students in Alberta that detailed their evening sleep habits and access to screens. Half of the kids had a television, DVD player or video game console in their bedroom. Just over one-fifth – 21 per cent – had a computer, while 17 per cent had a cellphone. All three types of screens were found in the bedrooms of 5 per cent of kids.

The more screens kids have at bed time, the worse it is for their health, the research suggests. Access to one gizmo made it 1.47 times more likely for a kid to be overweight compared with a child with no tech. Kids with three devices were 2.57 times more likely to be overweight.

Kids who stay up watching television on the sly for a little while may not seem to be doing anything all that harmful, but that’s not true, according to the study, which found that just one extra hour of sleep reduced the chances of being overweight by 28 per cent and cut the odds of being obese by 30 per cent.

The more sleep kids get, the more likely they are to engage in more physical activity – perhaps because they’re not completely zonked come recess – and make better choices of what to eat, according to the study, published in the journal Pediatric Obesity.

A study published earlier this month in the Canadian Medical Association Journal found a link between poor sleep in adolescents and increased body mass index, high levels of cholesterol and hypertension.

20 of the Coolest Augmented Reality Experiments in Education so far

Augmented reality is exactly what the name implies — a medium through which the known world fuses with current technology to create a uniquely blended interactive experience. While still more or less a nascent entity in the frequently Luddite education industry, more and more teachers, researchers, and developers contribute their ideas and inventions towards the cause of more interactive learning environments. Many of these result in some of the most creative, engaging experiences imaginable, and as adherence grows, so too will students of all ages.

- Second Life:Because it involves a Stephenson-esque reality where anything can happen, Second Life proved an incredibly valuable tool for educators hoping to reach a broad audience — or offering even more ways to learn for their own bands of students. Listing the numerous ways in which they utilized the virtual world means an entire article on its own, but a quick search will dredge up the online classes, demonstrations, discussions, lectures, presentations, debates, and other educational benefits.

- Augmented Reality Development Lab:Affiliated with such itty-bitty, insignificant companies as Google, Microsoft, and Logitech, the Augmented Reality Development Lab run by Digital Tech Frontier seeks to draw up projects that entertain as well as educate. The very core goal of the ARDL — which classrooms can purchase in kits at various price levels — involves creating interactive, three-dimensional objects for studying purposes.

- Reliving the Revolution:Karen Schrier harnessed GPS and Pocket PCs to bring the Battle of Lexington to her students through the Reliving the Revolution game, an AR experiment exploring some of the mysteries still shrouding the event — like who shot first! Players assume different historical roles and walk through everything on a real-life map of the Massachusetts city.

- PhysicsPlayground:One of the many, many engines behind PC games received a second life as an engaging strategy for illustrating the intricate ins and outs of physics, in a project known as PhysicsPlayground. It offers up an immersive, three-dimensional environment for experimenting, offering up a safer, more diverse space to better understand how the universe drives itself.

- MITAR Games:Developed by MIT’s Teacher Education Program and The Education Arcade, MITAR Games blend real-life locations with virtual individuals and scenarios for an educational experience that research proves entirely valid. Environmental Detectives, its first offering, sends users off on a mystery to discover the source of a devastating toxic spill.

- New Horizon:Some Japanese students and adults learning and reviewing English lessons enjoy the first generation of augmented reality textbooks, courtesy of publisher Tokyo Shoseki, for the New Horizon class. As a smartphone app, it takes advantage of built-in cameras to present animated character conversations when aligned with certain sections of pages.

- Occupational Safety Scaffolding:Professor Ron Dotson’s Construction Safety students receive a thorough education in establishing safe scaffolding space through three-dimensional demonstrations incorporating the real and the digital alike. A simple application of AR, to be certain, but one undoubtedly possessing the potential to save lives and limbs alike.

- FETCH! Lunch Rush:Education-conscious parents who want L’il Muffin and Junior to learn outside the classroom might want to consider downloading PBS Kids’ intriguing iPhone and iPod Touch app. Keep them entertained in the car or on the couch with a fun little game for ages six through eight meant to help them build basic math skills visually.

- Field trips:Augmented reality museums guide students and self-learners of all ages through interactive digital media centered around a specific theme — maybe even challenge them to play games along the way. HistoriQuest, for example, started life as the Civil War Augmented Reality Project and presented a heady blend of mystery gaming and very real stories.

- School in the Park Augmented Reality Experience:Third graders participating in the 12-year-old School in the Park program engage with AR via smartphones as they explore Balboa Park, the San Diego History Center, and the world-class San Diego Zoo. Not only do they receive exposure to numerous educational digital media resources, teachers also train them in creating their very own augmented reality experiences!

- QR Code scavenger hunts:Smartphones equipped with a QR code reader make for optimal tools when sending students on scavenger hunts across the classroom or school. The Daring Librarian, Gwyneth Anne Bronwynn, sends kids on an augmented reality, animated voyage through the library to figure out where to find everything and whom to ask for assistance.

- Mentira:Mentira takes place in Albuquerque and fuses fact and fiction, fantasy characters and real people, for the world’s first AR Spanish language learning game. It intentionally mimics the structure of a historical murder mystery novel and allows for far deeper, more effective engagement with native speakers than many classroom lessons.

- Driver’s ed:Toyota teamed up with Saatchi & Saatchi to deliver the world’s cleanest and safest test-drive via augmented reality. While the method has yet to catch on in the majority of driver’s education classes, it definitely makes for an impressive, effective alternative to keeping and maintaining a fleet of cars.

- Geotagging:Classrooms with smartphone access blend Google Earth and web albums such as Picasa or Instagram for a firsthand experience in geotagging and receiving a visual education about the world around them. More collaborative classrooms — like those hked together with Skype or another VOIP client – could use this as a way to nurture cross-cultural, geopolitical understanding.

- Dow Day:Jim Mathews’ augmented reality documentary and smartphone app brought University of Madison-Wisconsin students, faculty, staff, and visitors to the year 1967. As they traveled campus, participants’ smartphones called up actual footage of Vietnam War protests corresponding with their current locations.

- SciMorph:Using a webcam and printed target, young kids in need of some science (although, really, everyone is in need of some science) interact with the cute critter SciMorph, who teaches them about gravity, sound, and microbial structures. Each lesson involves exploring a specific zone within the game and opens users up to questions, quizzes, and talks.

- Imaginary Worlds:With PSPs in hand, Mansel Primary School students embarked on an artistic voyage, where downloaded images and QR codes merge and provide challenges to draw up personalized environments. The journey also pits them against monsters and requires a final write-up about how the immersive experience left an educational impact.

- Sky Map and Star Walk:Available on Android and iWhatever devices, these deceptively simple applications pack a megaton punch of education via an innovative augmented reality approach. Both involve pointing the gadget to the sky and seeing the names of the currently visible stars, planets, and constellations pop up, along with additional astronomical information.

- Handheld Augmented Reality Project:Harvard, MIT, and University of Wisconsin at Madison teamed up with a grant from the U.S. Department of Education and nurtured science and math skills to junior high kids using GPS navigators and Dell Axims. Moving through the school meant moving through a synched virtual environment, with each area presenting new challenges they must tackle before pressing forward.

- Project Glass:One of the most ambitious augmented reality initiatives comes straight from Google, who believes its Project Glass holds potential far beyond the classroom. Notoriously, it requires a pair of glasses versus the usual smartphones and laptops, and current experiments involve placing users in first-person extreme athletic experiences, snapping photos, and more.

Will the Common Core Accelerate or SLOW Innovation?

Some friends are working on a paper on the topic of common standards and innovation. The primary question is how and whether the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) will accelerate or slow innovation. The answer is that common standards are a big boon to innovation for four reasons:

1. CCSS and the shift to digital are coincident and complementary . Online assessment of the CCSS will respond for the need for better and cheaper assessments and will, in turn, accelerate shift to digital. First generation online assessment starting in 2015 will be step function improvement in most states. Administration of online assessments is one more reason for schools and districts to boost student access to technology and that will push thousands of schools to develop or adopt innovative blended models

2. CCSS are producing in big investment in digital content. I’ve suggested that common standards are like the iPhone for Edu, have brought up the rear in 30 states with low standards and launched an avalanche of innovation, including adaptive learning platforms like i-Ready and fully-digital, Common Core-aligned curriculums like the Pearson 1:1 launched at Huntsville in August.

The Compass Learning team added, “Just in the past 12 months, the team has developed and released hundreds of new learning activities, quizzes, and writing prompts to address the deeper, more rigorous Common Core State Standards.”

Foundations are making a big investment in innovative CCSS content including EduCurious,Khan Academy, ST Math, and MadCap.

MasteryConnect and LearnZillion are some of the scrappy startups banking on CCSS (as noted in a review of Bob Rothman’s Common Core book). Every week we see new engaging Common Core-aligned content, apps, and platforms — including lots of open educational resources (OER). The improved ability to share resources across state lines is a huge benefit.

3. Data standards will help. Common tagging strategies and data protocols will power new apps. As Frank Catalano’s recent blog pointed out, it’s still pretty confusing how all the data initiatives fit together (or don’t).

The Shared Learning Collaborative announced a new CEO yesterday.Iwan Streichenberger will lead the rollout of SLC technology to pilot districts next year.

In a recent paper DLN paper “Data Backpacks,” my co-authors and I argued that a thick gradebook of data should follow a student from grade to grade and school to school. The SLC will make that data — and more — available by teacher query through multiple apps. That kind of plumbing will lead to an ecosystem of innovation.

As several of these ecosystems blossom in the second half of this decade, they will mark the beginning of big data learning — and that should change everything.

4. Common Core is boosting equity. The most important benefit of the Common Core is real college and career readiness standards for all students. We can finally say that nearly every state is committed to preparing every student for viable life options. That commitment is likely to drive innovations in:

Competency-based learning that provides the time for kids that need it and acceleration opportunities for those that are ready

Funding that provides more opportunity and support for struggling students; and

School models that inspire lots of reading, writing, and problem solving.

Some critics complain about the cost of adoption, but the CCSS will save, not cost billions.

Some critics fear that CCSS and tests will constrict innovation. Anti-testing folks chime in on this one. But common expectations for reading, writing, and problem solving skills will make young people college eligible and give them a shot at family wage employment is not asking too much and leaves plenty of room for innovative school models.

Some critics blame the feds for being too supportive of the CCSS, but Race to the Top (RttT) produced more policy innovation in the six months leading up to the grants than any previous initiative.

There are some CCSS supporters that worry four or five states doing their own thing and six or eight states developing their own tests is a bad thing, but both will prove to be sources of innovation. Test vendors like ACT will continue to push the state testing consortia.

CCSS assessment in 2015 will be the pivotal event of this decade. Adoption of common standards will provide a significant boost to innovations in learning.