You’re Not Stuck In Traffic You Are Traffic

This started with a drivetime conversation about contemporary design with Joi Ito. We were stuck in traffic, and in our conversation, a question emerged about designers: This new generation of designers that work with complex adaptive systems. Why are they so much more humble than their predecessors who designed, you know, stuff?

The answer is another question, a hypothesis. The hypothesis is that most designers that are deliberately working with complex adaptive systems cannot help but be humbled by them. Maybe those who really design systems-interacting-with-systems approach their relationships to said systems with the daunting complexity of influence, rather than the hubris of definition or control.

The designers of complex adaptive systems are not strictly designing systems themselves. They are hintingthose systems towards anticipated outcomes, from an array of existing interrelated systems. These are designers that do not understand themselves to be in the center of the system. Rather, they understand themselves to be participants, shaping the systems that interact with other forces, ideas, events and other designers. This essay is an exploration of what it means to participate.

‘

‘

Mies understood that the geometry of his building would be perfect until people got involved’

If in 2016 this seems intuitive, recall that it is at odds with the heroic sensibility – and role – of the modern designer. Or the Modernist designer, in any case, in whose shadows many designers continue to toil. On the pre-eminent Modernist architect Mies Van der Rohe (director of the Bauhaus, among other legendary distinctions), Andrew Dolkart wrote: [1]

Mies understood that the geometry of his building would be perfect until people got involved. Once people moved in, they would be putting ornamental things along the window sills, they would be hanging all different kinds of curtains, and it would destroy the geometry. So there are no window sills; there is no place for you to put plants on the window. He supplied every single office with curtains, and all the curtains are exactly the same. And he supplied every window with venetian blinds, and the blinds open all the way, or they close all the way, or they stop halfway—those are the only places you can stop them, because he did not want venetian blinds everywhere or blinds set at angles.

The circumstances that led to such a position and practice – and the legacies that emerge from it – could be summarized in the question I have asked in every architecture review I’ve participated in: if tv shows have viewers, and cars have drivers, and books have readers, what word do architects use for the people who dwell in the buildings they make?

The Birth of the User

I haven’t met an architect with an answer to that yet and this isn’t really about architecture. Really. But in the meantime – in stark relief to the absence of the architectural term – the internet provided a model so useful that it sweeps across viewers, drivers, passengers, writers, readers, listeners, students, customers… bending all of these into the expressions of the user.

It’s hard to say exactly when the user was born, but it might be Don Norman at Apple in 1993 (referenced by Peter Merholz[2]):

“I invented the term [User Experience] because I thought Human Interface and usability were too narrow: I wanted to cover all aspects of the person’s experience with a system, including industrial design, graphics, the interface, the physical interaction, and the manual.”

In the 23 years since then, users have become the unit of measurement for entrepreneurial success. Like all units of measurement, it has acquired barnacle-like derivatives like MAU (monthly average users) and ARPU (average revenue per user.) If something has more users, it’s more successful than something with fewer users. If a user spends more time with something, it’s better than something they spend less time with.

To gain users – and to retain them – designers are drawing upon principles also set forth by Don Norman, in his 1986 “The Psychology of Everyday Things.” In the book, Norman proposes “User Centered Design” (UCD) which is still in active and successful use 20 years later by some of the largest global design consultancies.

Broadly, UCD optimizes around engagement with the needs, desires and shortcomings of the user (in stark opposition to, say, Mies van der Rohe) and explores design from the analysis and insight into what the User might need or want to do. Simply, it moves the center from the designer’s imagination of the system to the designer’s imagination of the user of the system.

Joe and Josephine, Henry Dreyfuss Associates 1974 (MIT Press) — you’ve never met them, but if you’re seated, you’re basically sitting in their chair.

Joe and Josephine, Henry Dreyfuss Associates 1974 (MIT Press) — you’ve never met them, but if you’re seated, you’re basically sitting in their chair.

In 2016, it’s nearly impossible to imagine a pre-user Miesian worldview generating anything successful. Placing human activity at the center of the design process – as opposed to a set of behaviors that must be controlled or accommodated – has become an instinctive and mandatory process. Aspects of this pre-date Norman’s “user,” e.g., Henry Dreyfuss’ “Joe and Josephine” (above) for whom all his products were designed. But where Joe and Josephine had anatomy, users have behavior, intention, desire.

It’s not the technical capacities of the internet; without UCD, Amazon couldn’t have put bookstores out of business, “ride-hailing” services couldn’t have broken the taxi industries in cities where they roll out, and digital music would never have broken the historical pricing and distribution practices of the record labels. Designers are appropriately proud of their roles in these disruptions; their insights into user desire and behavior are what made them possible.

But as designers construct these systems, what of the systems that interact with those systems? What about systems of local commerce and the civic engagement that is predicated upon it? Or the systems of unions that emerged after generations of labor struggles? Or the systems that provided compensation for some reasonable number of artists? When designers center around the user, where do the needs and desires of the other actors in the system go? The lens of the user obscures the view of the ecosystems it affects.

Robin Sloan recently addressed this in a post [3] about “Uber for food” startups like Sprig.

“[T]here’s more to any cafeteria than the serving line, and Sprig’s app offers no photograph of that other part. This is the Amazon move: absolute obfuscation of labor and logistics behind a friendly buy button. The experience for a Sprig customer is super convenient, almost magical; the experience for a chef or courier…? We don’t know. We don’t get to know. We’re just here to press the button.”

For users, this is what it means to be at the center: to be unaware of anything outside it. User-Centric Design means obscuring more than it surfaces. Sloan continues:

“I feel bad, truly, for Amazon and Sprig and their many peers—SpoonRocket, Postmates, Munchery, and the rest. They build these complicated systems and then they have to hide them, because the way they treat humans is at best mildly depressing and at worst burn-it-down dystopian.”

I have no idea what’s going on here but this is what I’m trying to say.

The user made perfect sense in the context in which it was originally defined: Human-Computer Interaction. UCD emphasized the practical and experiential aspects of the person at the keyboard, as opposed to the complex code and engineering behind it.

But we are no longer just using computers. We are using computers to use the world. The obscured and complex code and engineering now engages with people, resources, civics, communities and ecosystems.Should designers continue to privilege users above all others in the system? What would it mean to design for participants instead? For all the participants?

Designing for Participation.

Designing for participation is different than designing for use, in any case. Within architecture – which I refer to again precisely because participation is not native to the discipline – the idea emerged with increasing frequency as surfaces and materials took on greater dynamism. But perhaps the quintessential historical example is Cedric Price, who was working long before that dynamism was practical.

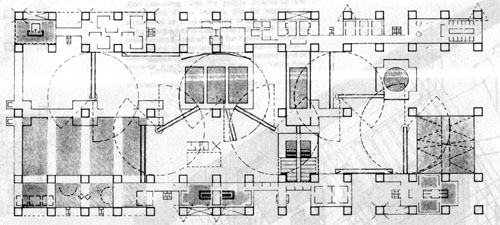

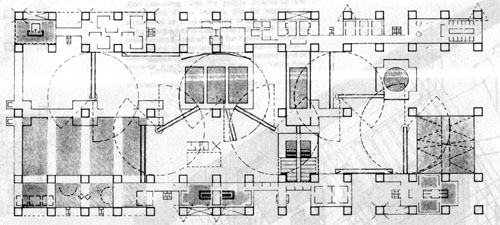

Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’ (1961) and if you’ve ever been to the Pompidou Center in Paris, you’re looking at what happens when this idea puts on a suit and gets a job.

Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’ (1961) and if you’ve ever been to the Pompidou Center in Paris, you’re looking at what happens when this idea puts on a suit and gets a job.

Price is well known for two projects: Fun Palace (1961) and Generator (1976) and though neither one was ever built, their genes can be isolated in the Centre George Pompidou and the so-called “smart home.” The Fun Palace (drawing, above) writes Stanley Matthews [4],

“…would challenge the very definition of architecture, for it was not even a conventional ‘building’ at all, but rather a kind of scaffold or framework, enclosing a socially interactive machine – a virtual architecture merging art and technology. In a sense, it was the realization of the long unfulfilled promise of Le Corbusier’s claims of a technologically informed architecture and the ‘machine for living’. It was not a museum, nor a school, theatre, or funfair, and yet it could be all of these things simultaneously or at different times. The Fun Palace was an environment continually interacting and responding to people.”

Designed in 1961, the Fun Palace in free exchange with many contemporaneous ideas, cybernetics not least of all. The Fun Palace was, writes Matthews, “like a swarm or meteorological system, its behaviour would be unstable, indeterminate, and unknowable in advance.”

This was wholly in line with the early cyberneticists like Gordon Pask (who noted in 1972, “now we’ve got the notion of a machine with an underspecified goal, the system that evolves…”)[5] But Price’s architecture was more than contemporary to cybernetics: it was infected by them. Pask himself organized the “Fun Palace Cybernetics Subcommittee.”

The Fun Palace was obviously quite radical as architecture, but far beyond its radical architectonic form (some of which was adopted by the Pompidou Center) was its more provocative proposal that the essential role for its designer was to create a context for participation.

This returns to the drivetime question about the designers of complex adaptive systems: Price was designing not for the uses he wished to see, but for all the uses he couldn’t imagine. This demands the ability to engage with the people in the building as participants, to see their desires and fears, and then to build contexts to address them. But it wasn’t strictly about interaction with the building; it was a fundamentally social engagement. As opposed to the “user” of a building who is interacting with a smart thermostat, the participants in a building are engaged with one another.

The social systems, however, are only one of many complex systems within which the Fun Palace is expressed. It stood outside any context of urban planning, or really any interaction with a broader system-based context (in which it is only a building, as opposed to a whole world.) It was designed for participants, but it denied that the building was participating in complex adaptive systems that were far greater than itself.

as best I know, this is pretty much what Cedric Price wanted to see happening in the Fun Palace

When the methodologies of design and science infect one another, however, design is not just a framework for participants, but something that is also, itself, participating. In the 2015 Hy-fi, a project for MoMA/PS1 by The Living (David Benjamin, above), it’s possible to see the various systems in active play. Analogous to Price’s Fun Palace, Hy-fi is a framework for participation, rather than a series of prescriptive uses.[6]

Hy-fi, however, is much more than the Price-like sensibilities that emphasize adaptability and context over structure and use. The materials used in Hy-fi are an innovative 100% organic material, manufactured from discarded corn stalks and bespoke “living root-like structures from mushrooms.” David Benjamin’s design of this material is inextricable from his design of the building. Hy-fi sits at one intersection between building and growing, rendering it as close to zero-carbon-emission development as anything we’ll find in New York City.

growing a building, 2015.

It’s not as simple as a kindness towards the planet, though indeed, it’s a love letter to earth. Here is a building that is composted, instead of demolished. Hy-fi rethinks what the building is and does, relative to its participation with the complex adaptive systems around it. From the MoMA summary:[7]

“The structure temporarily diverts the natural carbon cycle to produce a building that grows out of nothing but earth and returns to nothing but earth—with almost no waste, no energy needs, and no carbon emissions. This approach offers a new vision for society’s approach to physical objects and the built environment. It also offers a new definition of local materials, and a direct relationship to New York State agriculture and innovation culture, New York City artists and non-profits, and Queens community gardens.”

composting a building, 2015

composting a building, 2015

In other words, it’s not as simple as making sure that people are participating with the building (as Pask and Price conspired to do over 50 years ago.) Rather, the building is explicitly designed to participate in the built environment around it, as well as the natural environment beyond it, and further into local manufacturing, gardens and agriculture.

This is the designer working to highlight the active engagement with those systems. This is the alternative to the unexamined traditions of User-Centric Design, which renders these systems as either opaque or invisible.

Design as Participation.

To see this all the way through, designers can be reconsidered – in part through the various lenses of science – to become participants themselves.

Special participants, perhaps, but see above: the subject of the MoMA text is “the natural carbon cycle” that is diverted by the designer. The designer is one of many influences and directives in the system with their own hopes and plans. But mushrooms also have plans. The people who dance inside them have plans. And of course the natural carbon cycle has plans as well.

This recalls Ian Bogost’s take on Object Oriented Ontology (OOO), which he characterized succinctly in 2009[8]:

Ontology is the philosophical study of existence. Object-oriented ontology (“OOO” for short) puts things at the center of this study. Its proponents contend that nothing has special status, but that everything exists equally—plumbers, DVD players, cotton, bonobos, sandstone, and Harry Potter, for example. In particular, OOO rejects the claims that human experience rests at the center of philosophy, and that things can be understood by how they appear to us. In place of science alone, OOO uses speculation to characterize how objects exist and interact.

Some contemporary work suggests that we are not only designing for participation, but that design is a fundamentally participatory act, engaging systems that extend further than the constraints of individual (or even human) activity and imagination.

This is design as an activity that doesn’t place the designer or the user in the center.

Hans Haacke, ‘To the Population’ (Der Bevolkerung). Inside the Reichstag. This is Germany.

Hans Haacke, ‘To the Population’ (Der Bevolkerung). Inside the Reichstag. This is Germany.

Hans Haacke’s 2000 monument in the re-united German Reichstag – To the People, der Bevoelkerung – requested all the members of the German Parliament to collect soil from their various local regions, and deposit the dirt untouched, within the monument. What grows must be nurtured, collectively designated as the federal representation of Germany … on into the future, growing year by year. There are no brick-like constraints, as in Hy-fi. There is only a structural context for the complex – and wholly unpredictable – interaction of soil, seeds, water, and sunlight. Germany.

Maria Theresa Alves, ‘Seeds of Change’ ballast garden in Bristol. This is Bristol, which is to say: this is everywhere that Bristol went.

Maria Theresa Alves, ‘Seeds of Change’ ballast garden in Bristol. This is Bristol, which is to say: this is everywhere that Bristol went.

More recently, the Brazilian artist Maria Theresa Alves worked in Bristol England to identify “ballast seeds”: the seeds that were inadvertent stowaways in the colonial period, when sailors would load rocks for ballast in their ships. The rocks came from wherever they happened to land, to stabilize them on their way to wherever they were gong. In “Seeds of Change” (2015) she nurtured the reverse-colonizers of Bristol: marigolds from the Mediterranean, tassel flowers from the New World. These arrived quietly below the water line, silent migrants from centuries ago.

Alves happens to have started Brazil’s Green Party, which situates the work in a broader practice of participation. But in Bristol, she surfaces the complex systems that lie below deck, systems that are derivative effects of commerce, colonialism, and the dynamics of life at sea. It’s humbling to wander inside it, a reminder that it’s not always obvious who exactly colonizes whom.

The final work here is by the art and design collective Futurefarmers, started by Amy Franceschini in 1995. Famous to some for designing the logo for Twitter – itself an exercise in representing participatory engagement – much of their work centers around building infrastructure for participation. Some of the participation is between people, but much of it is with the complex natural systems that surround us. Their recent project “Flatbread Society: Land Grant 2014” is described by the Broad Art Museum[9] as:

“… a project that brings together farmers, oven builders, astronomers, artists, soil scientists, bakers, anthropologists, and others who share an interest in humankind’s long and complex relationship with grain.”

The work includes a flexible space for discussion and interaction (modeled after the trading floor of the Chicago grain exchanges) but more importantly, it also includes seeds that Futurefarmers have gathered from around the world, grains thought to be either extinct or useless. Further, there’s an oven. The grains are baked into flatbread together with anyone who cares to learn.

In the Flatbread Society work, like the work of Haacke and Alves, human activity can clearly be understood as only one of the systems that is in play. This is the inversion of User Centric Design. Rather than placing the human at the center of the work, the systems that surround us – systems we depend on – take the appropriate center stage in their complexity, mystery, in their unpredictability.

You’re Not Stuck In Traffic You Are Traffic

Small detail from Chris Burden’s ‘Metropolis II’ at LACMA. Every artist’s landscape captures a place, and a precise moment in time. This is America, and this precise moment is the 20th century.

Small detail from Chris Burden’s ‘Metropolis II’ at LACMA. Every artist’s landscape captures a place, and a precise moment in time. This is America, and this precise moment is the 20th century.

This started with a drivetime conversation about contemporary design with Joi Ito. We were stuck in traffic.

At the time, I remember thinking about David Foster Wallace, his essay and commencement address entitled “This is Water,” [10] and how he appealed to the students he was addressing:

“…I can spend time in the end-of-the-day traffic jam being angry and disgusted at all the huge, stupid, lane-blocking SUV’s and Hummers and V-12 pickup trucks burning their wasteful, selfish, forty-gallon tanks of gas, and I can dwell on the fact that the patriotic or religious bumper stickers always seem to be on the biggest, most disgustingly selfish vehicles driven by the ugliest, most inconsiderate and aggressive drivers, who are usually talking on cell phones as they cut people off in order to get just twenty stupid feet ahead in a traffic jam, and I can think about how our children’s children will despise us for wasting all the future’s fuel and probably screwing up the climate, and how spoiled and stupid and disgusting we all are, and how it all just sucks, and so on and so forth…

Look, if I choose to think this way, fine, lots of us do — except that thinking this way tends to be so easy and automatic it doesn’t have to be a choice. Thinking this way is my natural default-setting. It’s the automatic, unconscious way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the center of the world and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.”

There will always be designers to design the Hummers and the bumper stickers, and there will always be designers to design the web sites to propagate David Foster Wallace’s warnings and promises.

But a new generation of designers has emerged, concerned with designing strategies to subvert this “natural default-setting” in which each person understands themselves at the center of the world.

These designers do this by engaging with the complex adaptive systems that surround us, by revealing instead of obscuring, by building friction instead of hiding it, and by making clear that every one of us (designers included) are nothing more than participants in systems that have no center to begin with. These are designers of systems that participate – with us and with one another – systems that invite participation instead of demanding interaction.

We can build software to eat the world, or software to feed it. And if we are going to feed it, it will require a different approach to design, one which optimizes for a different type of growth, and one that draws upon –and rewards – the humility of the designers who participate within it.

–

EOM.

–

Many conversations led to this, most notably with Daisy Ginsberg as well as Kenyatta Cheese, Tricia Wang, Joe Riley, Karthik Dinakar, Joi Ito, and other friends, colleagues, participants.)