What Makes You Unique?

What makes human beings unique is we are naturally curious, creative and social.

These are the innate human capacities that cannot be automated and this is what we must focus on developing in our own lives as self-directed learners to remain indispensable in a knowledge-based economy.

The unique human qualities that robots and software can’t easily replicate are sensory awareness, creativity, and social intelligence. So, this is what a 21st-century education needs to develop.

I think re-imagining learning and education in this new era should start with asking some big questions about how we can better harness human potential. We desperately need to help more people develop their innate talents and gifts in the service of the greater good.

Asking Yourself The Big Questions:

Let’s start by asking some big questions about the nature of education and how we can unleash creative talent and initiative in a global, knowledge-based civilization connected by the Internet.

Here are a few questions that I feel are important to think deeply about:

1. What does it mean to be well-educated in the 21st century?

2. How does one live a creative, purpose-driven life that matters?

3. How do we nurture curiosity and wonder in ourselves and our children?

4. How do we inspire self-motivated learners able to solve their own problems?

5. How do we empowered citizens who actively serve their communities?

It’s people like you and me — not just institutions — that need to reimagine the role of learning in our lives by spending more time following our curiosity, exploring, creating, sharing and experimenting with our ideas.

We must foster a lifelong learning mindset in ourselves and the people we care about to navigate the challenges of 21st century education that require us to be constantly learning, adapting and developing our skills.

A 21st Century Education:

In the thousands of hours I’ve spent studying the nature of learning and creativity, and how to connect these two capacities in a knowledge-based economy, there have been some thought-provoking authors who have stood out as shining lights.

What I want to do is share with you some of their most profound insights and quotes to illustrate the characteristics of 21st-century education and self-directed learning that I strongly believe we all need to develop:

1. We need to be creative problem solvers.

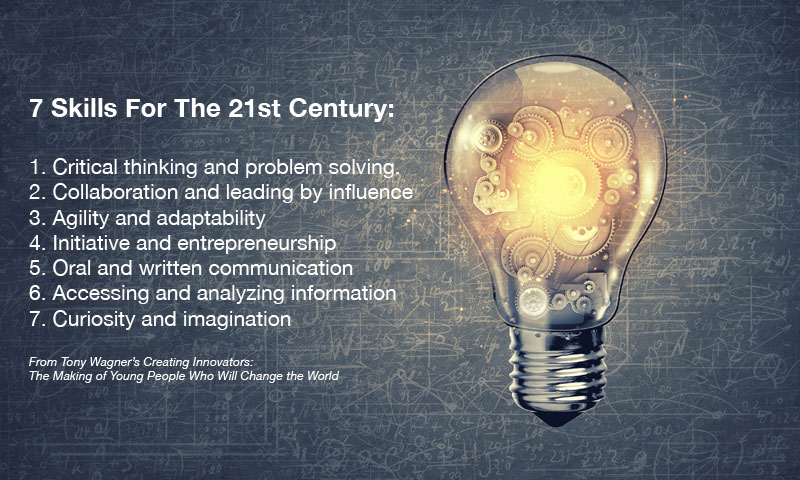

Play, passion and purpose. That’s what makes someone creative. Tony Wagner of the Harvard Innovation Lab makes a compelling case in his books that our current model of education is obsolete and irrelevant to most people’s lives and work.

Quotes from Tony Wagner, author of Creating Innovators: The Making of Young People Who Will Change the World:

“The world doesn’t care what you know. What the world cares about is what you do with what you know.”

“Students who only know how to perform well in today’s education system—get good grades and test scores, and earn degrees—will no longer be those who are most likely to succeed. Thriving in the twenty-first century will require real competencies, far more than academic credentials.”

“Now, adults need to be able to ask great questions, critically analyze information, form independent opinions, collaborate, and communicate effectively. These are the skills essential for both career and citizenship.”

“Education needs to help our youth discover their passions and purpose in life, develop the critical skills needed to be successful in pursuing their goals, be inspired on a daily basis to do their very best, and be active and informed citizens.”

“Most policy makers—and many school administrators—have absolutely no idea what kind of instruction is required to produce students who can think critically and creatively, communicate effectively, and collaborate versus merely score well on a test.”

“U.S. education is failing, in large part, because of the misguided belief that it’s imperative to test on a massive scale.”

“A recent report by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation concluded that “The United States has made the least progress of the 40 nations/regions [studied] in improvement in international competitiveness and innovation capacity over the last decade.”

“Our “leaders”—on both the left and the right side of the aisle—continue to claim that our schools are failing and in need of reform while, in reality, our education system is obsolete and needs reimagining.”

“With well-designed pedagogy, we can empower kids with critical skills and help them turn passions into decisive life advantages. The role of education is no longer to teach content, but to help our children learn—in a world that rewards the innovative and punishes the formulaic.”

“An overarching goal of education should be to immerse students in the beauty and inspiration of their surrounding world.”

2. We all need to adopt a growth mindset.

These are the best of times for those with a growth mindset because it gives you the flexibility to adapt and rise to any challenge. But these are the worst of times for those stuck in the rut of a fixed mindset and unable to change. Reading Carol Dweck‘s book Mindset and adopting a stronger growth mindset transformed my life.

Quotes from Carol Dweck, author of Mindset: The New Psychology of Success:

“Did I win? Did I lose? Those are the wrong questions. The correct question is: Did I make my best effort?” If so, he says, “You may be outscored but you will never lose.”

“We like to think of our champions and idols as superheroes who were born different from us. We don’t like to think of them as relatively ordinary people who made themselves extraordinary.”

“No matter what your ability is, effort is what ignites that ability and turns it into accomplishment.”

“I believe ability can get you to the top,” says coach John Wooden, “but it takes character to keep you there.… It’s so easy to … begin thinking you can just ‘turn it on’ automatically, without proper preparation. It takes real character to keep working as hard or even harder once you’re there. When you read about an athlete or team that wins over and over and over, remind yourself, ‘More than ability, they have character.’ ”

“After seven experiments with hundreds of children, we had some of the clearest findings I’ve ever seen: Praising children’s intelligence harms their motivation and it harms their performance. How can that be? Don’t children love to be praised? Yes, children love praise. And they especially love to be praised for their intelligence and talent. It really does give them a boost, a special glow—but only for the moment. The minute they hit a snag, their confidence goes out the window and their motivation hits rock bottom. If success means they’re smart, then failure means they’re dumb. That’s the fixed mindset.”

“Why waste time proving over and over how great you are, when you could be getting better? Why hide deficiencies instead of overcoming them? Why look for friends or partners who will just shore up your self-esteem instead of ones who will also challenge you to grow? And why seek out the tried and true, instead of experiences that will stretch you? The passion for stretching yourself and sticking to it, even (or especially) when it’s not going well, is the hallmark of the growth mindset. This is the mindset that allows people to thrive during some of the most challenging times in their lives.”

“Mindset change is not about picking up a few pointers here and there. It’s about seeing things in a new way. When people…change to a growth mindset, they change from a judge-and-be-judged framework to a learn-and-help-learn framework. Their commitment is to growth, and growth take plenty of time, effort, and mutual support.”

“Parents think they can hand children permanent confidence—like a gift—by praising their brains and talent. It doesn’t work, and in fact has the opposite effect. It makes children doubt themselves as soon as anything is hard or anything goes wrong. If parents want to give their children a gift, the best thing they can do is to teach their children to love challenges, be intrigued by mistakes, enjoy effort, and keep on learning. That way, their children don’t have to be slaves of praise. They will have a lifelong way to build and repair their own confidence.”

“Praise should deal, not with the child’s personality attributes, but with his efforts and achievements.”

“This is something I know for a fact: You have to work hardest for the things you love most.”

“John Wooden, the legendary basketball coach, says you aren’t a failure until you start to blame. What he means is that you can still be in the process of learning from your mistakes until you deny them.”

“As growth-minded leaders, they start with a belief in human potential and development—both their own and other people’s. Instead of using the company as a vehicle for their greatness, they use it as an engine of growth—for themselves, the employees, and the company as a whole.”

“Why waste time proving over and over how great you are, when you could be getting better?”

“Research shows that normal young children misbehave every three minutes.”

“If you don’t give anything, don’t expect anything. Success is not coming to you, you must come to it.”

“The students with growth mindset completely took charge of their learning and motivation.”

“Many growth-minded people didn’t even plan to go to the top. They got there as a result of doing what they love. It’s ironic: The top is where the fixed-mindset people hunger to be, but it’s where many growth-minded people arrive as a by-product of their enthusiasm for what they do.”

“When you enter a mindset, you enter a new world. In one world–the world of fixed traits–success is about proving you’re smart or talented. Validating yourself. In the other–the world of changing qualities–it’s about stretching yourself to learn something new. Developing yourself.”

3. We need to be self-motivated learners.

I strongly believe in the value of following your curiosity and finding what motivates you. In Drive, Daniel Pink brilliantly collects the psychology research into how high performers become self-motivated. It boils down to creating our own self-directed productivity systems that allow us to develop a higher degree of autonomy, mastery and purpose in our lives.

Quotes from Daniel Pink, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us:

“Control leads to compliance; autonomy leads to engagement.”

“While complying can be an effective strategy for physical survival, it’s a lousy one for personal fulfillment. Living a satisfying life requires more than simply meeting the demands of those in control. Yet in our offices and our classrooms we have way too much compliance and way too little engagement. The former might get you

through the day, but only the latter will get you through the night.”

“The problem with making an extrinsic reward the only destination that matters is that some people will choose the quickest route there, even if it means taking the low road. Indeed, most of the scandals and misbehavior that have seemed endemic to modern life involve shortcuts.”

“One source of frustration in the workplace is the frequent mismatch between what people must do and what people can do. When what they must do exceeds their capabilities, the result is anxiety. When what they must do falls short of their capabilities, the result is boredom. But when the match is just right, the results can be glorious. This is the essence of flow.”

“The monkeys solved the puzzle simply because they found it gratifying to solve puzzles. They enjoyed it. The joy of the task was its own reward.”

“Why reach for something you can never fully attain? But it’s also a source of allure. Why not reach for it? The joy is in the pursuit more than the realization. In the end, mastery attracts precisely because mastery eludes.”

“Goals that people set for themselves and that are devoted to attaining mastery are usually healthy. But goals imposed by others–sales targets, quarterly returns, standardized test scores, and so on–can sometimes have dangerous side effects.”

“We have three innate psychological needs—competence, autonomy, and relatedness. When those needs are satisfied, we’re motivated, productive, and happy.”

“Human beings have an innate inner drive to be autonomous, self-determined, and connected to one another. And when that drive is liberated, people achieve more and live richer lives.”

“For artists, scientists, inventors, schoolchildren, and the rest of us, intrinsic motivation—the drive do something because it is interesting, challenging, and absorbing—is essential for high levels of creativity.”

“Being a professional,” Julius Erving once said, “is doing the things you love to do, on the days you don’t feel like doing them.”

“Management isn’t about walking around and seeing if people are in their offices,” he told me. It’s about creating conditions for people to do their best work.”

4. We need to create systems to focus our minds and achieve full engagement in our work.

Nothing has made a greater impact in my life then learning to apply flow psychology to my learning and work. I am so grateful to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the Godfather of Flow research, who has taught me that I can prime my mind and body through meditation and flow practices to feel my best and perform my best consistently.

Quotes from Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, author of Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience:

“A joyful life is an individual creation that cannot be copied from a recipe.”

“Control of consciousness determines the quality of life.”

“These examples suggest what one needs to learn is to control attention. In principle any skill or discipline one can master on one’s own will serve: meditation and prayer if one is so inclined; exercise, aerobics, martial arts for those who prefer concentrating on physical skills. Any specialization or expertise that one finds enjoyable and where one can improve one’s knowledge over time. The important thing, however, is the attitude toward these disciplines. If one prays in order to be holy, or exercises to develop strong pectoral muscles, or learns to be knowledgeable, then a great deal of the benefit is lost. The important thing is to enjoy the activity for its own sake, and to know that what matters is not the result, but the control one is acquiring over one’s attention.”

“But it is impossible to enjoy a tennis game, a book, or a conversation unless attention is fully concentrated on the activity.”

“It is when we act freely, for the sake of the action itself rather than for ulterior motives, that we learn to become more than what we were. When we choose a goal and invest ourselves in it to the limits of concentration, whatever we do will be enjoyable. And once we have tasted this joy, we will redouble our efforts to taste it again. This is the way the self grows.”

“Most enjoyable activities are not natural; they demand an effort that initially one is reluctant to make. But once the interaction starts to provide feedback to the person’s skills, it usually begins to be intrinsically rewarding.”

“To overcome the anxieties and depressions of contemporary life, individuals must become independent of the social environment to the degree that they no longer respond exclusively in terms of its rewards and punishments. To achieve such autonomy, a person has to learn to provide rewards to herself. She has to develop the ability to find enjoyment and purpose regardless of external circumstances.”

“Contrary to what we usually believe, moments like these, the best moments in our lives, are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times—although such experiences can also be enjoyable, if we have worked hard to attain them. The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile. Optimal experience is thus something that we

make happen. For a child, it could be placing with trembling fingers the last block on a tower she has built, higher than any she has built so far; for a swimmer, it could be trying to beat his own record; for a violinist, mastering an intricate musical passage. For each person there are thousands of opportunities, challenges to expand ourselves.”

“Few things are sadder than encountering a person who knows exactly what he should do, yet cannot muster enough energy to do it. “He who desires but acts not,” wrote Blake with his accustomed vigor, “Breeds pestilence.”

“Of all the virtues we can learn no trait is more useful, more essential for survival, and more likely to improve the quality of life than the ability to transform adversity into an enjoyable challenge.”

5. We need to actively learn new things and rely less on formal education.

Few intellectuals offer analysis and insight as profoundly challenging to our worldview as social critic Ivan Illich. He saw how the materialization of human values and the debt-fueled status anxiety at the heart of modern Western consumer culture was a race to nowhere that would eventually lead to the breakdown of society.

Quotes from Ivan Illich, author of Deschooling Society:

“School is the advertising agency which makes you believe that you need the society as it is.”

“Man must choose whether to be rich in things or in the freedom to use them.”

“Most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting. Most people learn best by being “with it,” yet school makes them identify their personal, cognitive growth with elaborate planning and manipulation.”

“School has become the world religion of a modernized proletariat, and makes futile promises of salvation to the poor of the technological age.”

“In a consumer society there are inevitably two kinds of slaves: the prisoners of addiction and the prisoners of envy.”

“The re-establishment of an ecological balance depends on the ability of society to counteract the progressive materialization of values. The ecological balance cannot be re-established unless we recognize again that only persons have ends and only persons can work towards them.”

“Schools are designed on the assumption that there is a secret to everything in life; that the quality of life depends on knowing that secret; that secrets can be known only in orderly successions; and that only teachers can properly reveal these secrets. An individual with a schooled mind conceives of the world as a pyramid of classified packages accessible only to those who carry the proper tags.”

“School initiates young people into a world where everything can be measured, including their imaginations, and, indeed, man himself.”

“Neither revolution nor reformation can ultimately change a society, rather you must tell a new powerful tale, one so persuasive that it sweeps away the old myths and becomes the preferred story, one so inclusive that it gathers all the bits of our past and our present into a coherent whole, one that even shines some light into the future so that we can take the next step… If you want to change a society, then you have to tell an alternative story.”

“Effective health care depends on self-care; this fact is currently heralded as if it were a discovery.”

“We can only live changes: we cannot think our way to humanity. Every one of us, every group, must become the model of that which we desire to create.”

“We cannot go beyond the consumer society unless we first understand that obligatory public schools inevitably reproduce such a society, no matter what is taught in them.”

“I believe that a desirable future depends on our deliberately choosing a life of action over a life of consumption, on our engendering a lifestyle which will enable us to be spontaneous, independent, yet related to each other, rather than maintaining a lifestyle which only allows to make and unmake, produce and consume – a style of life which is merely a way station on the road to the depletion and pollution of the environment. The future depends more upon our choice of institutions which support a life of action than on our developing new ideologies and technologies.”

“In schools, including universities, most resources are spent to purchase the time and motivation of a limited number of people to take up predetermined problems in a ritually defined setting. The most radical alternative to school would be a network or service which gave each man the same opportunity to share his current concern with others motivated by the same concern.”

“Observations of the sickening effect of programmed environments show that people in them become indolent, impotent, narcissistic and apolitical. The political process breaks down, because people cease to be able to govern themselves; they demand to be managed.”

“Societies in which most people depend for most of their goods and services on the personal whim, kindness, or skill of another are called underdeveloped, while those in which living has been transformed into a process of ordering from an all-encompassing store catalogue are called advanced.”

“The public is indoctrinated to believe that skills are valuable and reliable only if they are the result of formal schooling.”

“School prepares people for the alienating institutionalization of life, by teaching the necessity of being taught. Once this lesson is learned, people loose their incentive to develop independently; they no longer find it attractive to relate to each other, and the surprises that life offers when it is not predetermined by institutional definition are closed.”

“A second major illusion on which the school system rests is that most learning is the result of teaching. Teaching, it is true, may contribute to certain kinds of learning under certain circumstances. But most people acquire most of their knowledge outside school, and in school only insofar as school, in a few rich countries, has become their place of confinement during an increasing part of their lives.”

6. We need to spend time each week exploring and exercising in natural environments.

The scientific research is unanimous, people that regularly unplug and spend time in nature are much healthier, happier and more creative. In Last Child In The Woods, Richard Louv explores how the sedentary lifestyles of children (and adults) are ruining their long-term physical and mental health.

Quotes from Richard Louv, author of Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder:

“An environment-based education movement–at all levels of education–will help students realize that school isn’t supposed to be a polite form of incarceration, but a portal to the wider world.”

“Unlike television, nature does not steal time; it amplifies it. Nature offers healing for a child living in a destructive family or neighborhood. It is often overlooked as a healing balm for the emotional hardships in a child’s life.”

“Passion is lifted from the earth itself by the muddy hands of the young; it travels along grass-stained sleeves to the heart. If we are going to save environmentalism and the environment, we must also save an endangered indicator species: the child in nature.”

“We have such a brief opportunity to pass on to our children our love of this Earth, and to tell our stories. These are the moments when the world is made whole. In my children’s memories, the adventures we’ve had together in nature will always exist.”

“An indoor (or backseat) childhood does reduce some dangers to children; but other risks are heightened, including risks to physical and psychological health, risk to children’s concept and perception of community, risk to self-confidence and the ability to discern true danger.”

“Studies of children in playgrounds with both green areas and manufactured play areas found that children engaged in more creative forms of play in the green areas.”

“Numerous studies document the benefits to students from school grounds that are ecologically diverse and include free play areas, habitats for wildlife, walking trails, and gardens.”

“Natural play strengthens children’s self-confidence and arouses their senses—their awareness of the world and all that moves in it, seen and unseen.”

“Nature is one of the best antidotes to fear.”

“This tree house became our galleon, our spaceship, our Fort Apache…Ours was a learning tree. Through it we learned to trust ourselves and our abilities.”

“Children need nature for the healthy development of their senses, and therefore, for learning and creativity.”

“Nature—the sublime, the harsh, and the beautiful—offers something that the street or gated community or computer game cannot. Nature presents the young with something so much greater than they are; it offers an environment where they can easily contemplate infinity and eternity.”

“Nature is a teacher. A teacher that is immensely old and extraordinarily wise. A teacher that can teach subjects that no human can teach. A teacher that will go at any pace.”

“Increasingly the evidence suggests that people benefit so much from contact with nature that land conservation can now be viewed as a public health strategy.”

“Stress reduction, greater physical health, a deeper sense of spirit, more creativity, a sense of play, even a safer life-these are the rewards that await a family when it invites more nature into children’s lives.”

“The physical exercise and emotional stretching that children enjoy in unorganized play is more varied and less time-bound than is found in organized sports. Playtime—especially unstructured, imaginative, exploratory play—is increasingly recognized as an essential component of wholesome child development.”

“If a child never sees the stars, never has meaningful encounters with other species, never experiences the richness of nature, what happens to that child?”

7. We need to develop our creative gifts and talents through play.

Work doesn’t have to suck. I’ve found that through playful creating and following my curiosity I’ve been able to develop my creative instincts where I can rely on them to support myself. Peter Gray makes the passionate argument that play should be at the center of 21st century education

.

Dr. Peter Gray, author of Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life:

“Children come into the world exquisitely designed, and strongly motivated, to educate themselves. They don’t need to be forced to learn; in fact, coercion undermines their natural desire to learn.”

“Today anyone who can get their hands on a computer with Internet access— even street kids in India— can access the world’s entire body of knowledge and ideas, all beautifully organized and available through easy-to-use search engines. For almost anything you want to do, you can find instructions and video on the Internet. For almost any idea you want to think about, you can find arguments and counterarguments on the Internet, and even join a discussion about it. This is far more conducive to intellectual development than the one-right-answer approach of the standard school system.”

“The idea that you have to go to school to learn anything or to become a critical thinker is patently ridiculous to any kid who knows how to access the Internet, and so it is becoming harder and harder to justify top-down schooling.”

“How did we come to the conclusion that the best way to educate students is to force them into a setting where they are bored, unhappy, and anxious.”

“We have forgotten that children are designed by nature to learn through self-directed play and exploration, and so, more and more, we deprive them of freedom to learn, subjecting them instead to the tedious and painfully slow learning methods devised by those who run the schools.”

“Everyone who has ever been to school knows that school is prison, but almost nobody beyond school age says it is. It’s not polite. We all tiptoe around the truth because admitting it would make us seem cruel and would point a finger at well-intentioned people doing what they believe to be essential. . . . A prison, according to the common, general definition, is any place of involuntary confinement and restriction of liberty. In school, as in adult prisons, the inmates are told exactly what they must do and are punished for failure to comply. Actually, students in school must spend more time doing exactly what they are told than is true of adults in penal institutions. Another difference, of course, is that we put adults in prison because they have committed a crime, while we put children in school because of their age.”

“Sadly, in many cases, the assumption that children are incompetent, irresponsible, and in need of constant direction and supervision becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The children themselves become convinced of their incompetence and irresponsibility, and may act accordingly. The surest way to foster any trait in a person is to treat that person as if he or she already has it.”

“Several experiments have shown that playing fast-paced action video games can quite markedly increase players’ scores on tests of visuospatial ability, including components of standard IQ tests.”

“Self-education through play and exploration requires enormous amounts of unscheduled time—time to do whatever one wants to do, without pressure, judgment, or intrusion from authority figures. That time is needed to make friends, play with ideas and materials, experience and overcome boredom, learn from one’s own mistakes, and develop passions.”

“If we love our children and want them to thrive, we must allow them more time and opportunity to play, not less. Yet policymakers and powerful philanthropists are continuing to push us in the opposite direction — toward more schooling, more testing, more adult direction of children, and less opportunity for free play.”

“By “true learning” and “deep knowledge,” I mean children’s incorporation of ideas and information into lasting ways of understanding and responding to the world around them. This is very different from superficial knowledge that is acquired solely for the purpose of passing a test and is forgotten shortly after the test is over.”

“Schooling that children are forced to endure—in which the subject matter is imposed by others and the “learning” is motivated by extrinsic rewards and punishments rather than by the children’s true interests—turns learning from a joyful activity into a chore, to be avoided whenever possible. Coercive schooling, which tragically is the norm in our society, suppresses curiosity and overrides children’s natural ways of learning. It also promotes anxiety, depression and feelings of helplessness that all too often reach pathological levels.”

“Repetition and memorization of imposed lessons are indeed tedious work for children, whose instincts urge them constantly to play and think freely, raise their own questions, and explore the world in their own ways. Children did not adapt well to forced schooling, and in many cases they rebelled. This was no surprise to the adults. By this point in history, the idea that children’s own preferences had any value had been pretty well forgotten. Brute force, long used to keep children on task in fields and factories, was transported into the classroom to make children learn.”

“It is nothing short of a miracle that the modern methods of instruction have not yet entirely strangled the holy curiosity of inquiry; for this delicate plant, aside from stimulation, stands mainly in need of freedom; without this it goes to wreck and ruin without fail. It is a very grave mistake to think that the enjoyment of seeing and searching can be promoted by means of coercion and a sense of duty.”

8. We need to recognize our inner genius and resist the conformity of mass culture.

When I read John Taylor Gatto‘s Weapons of Mass Instruction it became clear why I felt that school was a prison as a child. The damage that our one-size-fits-all education system does to many highly creative and energetic individuals is a tragedy that is our greatest waste of “natural resources”.

Quotes from John Taylor Gatto, author of Weapons of Mass Instruction:

“Whatever an education is, it should make you a unique individual, not a conformist; it should furnish you with an original spirit with which to tackle the big challenges; it should allow you to find values which will be your roadmap through life; it should make you spiritually rich, a person who loves whatever you are doing, wherever you are, whomever you are with; it should teach you what is important, how to live and how to die.”

“I’ve concluded that genius is as common as dirt. We suppress genius because we haven’t yet figured out how to manage a population of educated men and women. The solution, I think, is simple and glorious. Let them manage themselves.”

“Independent study, community service, adventures and experience, large doses of privacy and solitude, a thousand different apprenticeships — the one-day variety or longer — these are all powerful, cheap, and effective ways to start a real reform of schooling. But no large-scale reform is ever going to work to repair our damaged children and our damaged society until we force open the idea of “school” to include family as the main engine of education. If we use schooling to break children away from parents — and make no mistake, that has been the central function of schools since John Cotton announced it as the purpose of the Bay Colony schools in 1650 and Horace Mann announced it as the purpose of Massachusetts schools in 1850 — we’re going to continue to have the horror show we have right now.”

“In our secular society, school has become the replacement for church, and like church it requires that its teachings must be taken on faith.”

“This was once a land where every sane person knew how to build a shelter, grow food, and entertain one another. Now we have been rendered permanent children. It’s the architects of forced schooling who are responsible for that.”

“What’s gotten in the way of education in the United States is a theory of social engineering that says there is ONE RIGHT WAY to proceed with growing up.”

“Schools teach exactly what they are intended to teach and they do it well: how to be a good Egyptian and remain in your place in the pyramid.”

“Schools were designed by Horace Mann and Barnard Sears and Harper of the University of Chicago and Thorndyke of Columbia Teachers College and some other men to be instruments of the scientific management of a mass population. Schools are intended to produce through the application of formulae, formulaic human beings whose behavior can be predicted and controlled.”

“The old system where every child was locked away and set into nonstop, daily cut throat competition with every other child for silly prizes called grades is broken beyond repair. If it could be fixed it could have been fixed by now.”

“The lesson of report cards, grades, and tests is that children should not trust themselves or their parents but should instead rely on the evaluation of certified officials. People need to be told what they are worth.”

“School trains children to be employees and consumers; teach your own to be leaders and adventurers. School trains children to obey reflexively; teach your own to think critically and independently. Well-schooled kids have a low threshold for boredom; help your own to develop an inner life so that they’ll never be bored. Urge them to take on the serious material, the grown-up material, in history, literature, philosophy, music, art, economics, theology – all the stuff schoolteachers know well enough to avoid. Challenge your kids with plenty of solitude so that they can learn to enjoy their own company, to conduct inner dialogues. Well-schooled people are conditioned to dread being alone, and they seek constant companionship through the TV, the computer, the cell phone, and through shallow friendships quickly acquired and quickly abandoned. Your children should have a more meaningful life, and they can.”

“Bit by bit I began to devise guerrilla exercises to allow as many of the kids I taught as possible the raw material people always use to educate themselves: privacy, choice, freedom from surveillance, and as broad a range of situations and human associations as my limited power and resources could manage. In simpler terms, I tried to maneuver them into positions where they would have the chance to be their own teachers and make themselves the major text of their own education.”

“A few years back one of the schools at Harvard, perhaps the School of Government, issued some advice to its students on planning a career in the new international economy it believed was arriving. It warned sharply that academic classes and professional credentials would count for less and less when measured against real world training. Ten qualities were offered as essential to successfully adapting to the rapidly changing world of work. See how many of those you think are regularly taught in the schools of your city or state:

1) The ability to define problems without a guide.

2) The ability to ask hard questions which challenge prevailing assumptions.

3) The ability to work in teams without guidance.

4) The ability to work absolutely alone.

5) The ability to persuade others that your course is the right one.

6) The ability to discuss issues and techniques in public with an eye to reaching decisions about policy.

7) The ability to conceptualize and reorganize information into new patterns.

8) The ability to pull what you need quickly from masses of irrelevant data.

9) The ability to think inductively, deductively, and dialectically.

10) The ability to attack problems heuristically.”

“Close reading of tough-minded writing is still the best, cheapest, and quickest method known for learning to think for yourself… Reading, and rigorous discussion of that reading in a way that obliges you to formulate a position and support it against objections, is an operational definition of education… reading, analysis, and discussion is the way we develop reliable judgment, the principle way we come to penetrate covert movements behind the facade of public appearances.”

9. We need to risk failure and learn quickly from our mistakes.

Few people have done more than Sir Ken Robinson to wake people up about the short-sightedness of the current obsession with standardization and measurement. Our model of schooling is killing the most valuable resources we have: curiosity and creativity. He argues that creativity is just as important as literacy in a knowledge-based economy.

Sir Ken Robinson, author of Out Of Our Minds: Learning To Be Creative

“If you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original.”

“We stigmatize mistakes. And we’re now running national educational systems where mistakes are the worst thing you can make — and the result is that we are educating people out of their creative capacities.”

“The fact is that given the challenges we face, education doesn’t need to be reformed — it needs to be transformed. The key to this transformation is not to standardize education, but to personalize it, to build achievement on discovering the individual talents of each child, to put students in an environment where they want to learn and where they can naturally discover their true passions.”

“Ironically, Alfred Binet, one of the creators of the IQ test, intended the test to serve precisely the opposite function. In fact, he originally designed it (on commission from the French government) exclusively to identify children with special needs so they could get appropriate forms of schooling. He never intended it to identify degrees of intelligence or “mental worth.” In fact, Binet noted that the scale he created “does not permit the measure of intelligence, because intellectual qualities are not superposable, and therefore cannot be measured as linear surfaces are measured.” Nor did he ever intend it to suggest that a person could not become more intelligent over time. “Some recent thinkers,” he said, “[have affirmed] that an individual’s intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity that cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism; we must try to demonstrate that it is founded on nothing.”

“Creativity is as important now in education as literacy and we should treat it with the same status.”

“Imagination is the source of every form of human achievement. And it’s the one thing that I believe we are systematically jeopardizing in the way we educate our children and ourselves.”

“We have sold ourselves into a fast food model of education, and it’s impoverishing our spirit and our energies as much as fast food is depleting our physical bodies.”

“One problem with the systems of assessment that use letters and grades is that they are usually light on description and heavy on comparison. Students are sometimes given grades without really knowing what they mean, and teachers sometimes give grades without being completely sure why. A second problem is that a single letter or number cannot convey the complexities of the process that it is meant to summarize. And some outcomes cannot be adequately expressed in this way at all. As the noted educator Elliot Eisner once put it, “Not everything important is measurable and not everything measurable is important.”

“You create your own life by how you see the world and your place in it.”

“Although mindfulness does not remove the ups and downs of life, it changes how experiences like losing a job, getting a divorce, struggling at home or at school, births, marriages, illnesses, death and dying influence you and how you influence the experience. . . . In other words, mindfulness changes your relationship to life.”

“If you are considering earning your living from your Element, it’s important to bear in mind that you not only have to love what you do; you should also enjoy the culture and the tribes that go with it.”

“Very many people go through their whole lives having no real sense of what their talents may be, or if they have any to speak of.”

“Human resources are like natural resources; they’re often buried deep. You have to go looking for them; they’re not just lying around on the surface.”

“Education can be stifling, no question about it. One of the reasons is that education — and American education in particular, because of the standardization — is the opposite of three principles I have outlined: it does not emphasize diversity or individuality; it’s not about awakening the student, it’s about compliance; and it has a very linear view of life, which is simply not the case with life at all.”

“Nobody else can make anybody else learn anything. You cannot make them. Anymore than if you are a gardener you can make flowers grow, you don’t make the flowers grow. You don’t sit there and stick the petals on and put the leaves on and paint it. You don’t so that. The flower grows itself. Your job if you are any good at it is to provide the optimum conditions for it to do that, to allow it to grow itself.”

“You can’t be a creative thinker if you’re not stimulating your mind, just as you can’t be an Olympic athlete if you don’t train regularly.”

“Passion is the driver of achievement in all fields. Some people love doing things they don’t feel they’re good at. That may be because they underestimate their talents or haven’t yet put the work in to develop them.”

“I define creativity as the process of having original ideas that have value.”

“Many highly talented, brilliant, creative people think they’re not — because the thing they were good at at school wasn’t valued, or was actually stigmatized.”

“Curiosity is the engine of achievement.”

“To be creative you actually have to do something.”

10. We need to make ourselves indispensable by getting creative with our life and work.

Few people in the world understand the paradigm shift happening in today’s economy better than Seth Godin. His books are inspiring manifestos that call you to take control of your life and develop your creative talents and gifts to serve others. I’ve read nearly all his books but Linchpin remains my favorite and I re-read it every year.

Seth Godin, author of Linchpin: Are You Indispensable?

“The only people who get paid enough, get paid what they’re worth are people who don’t follow the instruction book, who create art, who are innovative, who work without a map. That option is now available to everyone so take it.”

“Perhaps your challenge isn’t finding a better project or a better boss. Perhaps you need to get in touch with what it means to feel passionate. People with passion look for ways to make things happen.”

“Treasure what it means to do a day’s work. It’s our one and only chance to do something productive today, and it’s certainly not available to someone merely because he is the high bidder. A day’s work is your chance to do art, to create a gift, to do something that matters. As your work gets better and your art becomes more important, competition for your gifts will increase and you’ll discover that you can be choosier about whom you give them to.”

“The only way to get what you’re worth is to stand out, to exert emotional labor, to be seen as indispensable, and to produce interactions that organizations and people care deeply about.”

“Art isn’t only a painting. Art is anything that’s creative, passionate, and personal. And great art resonates with the viewer, not only with the creator.

What makes someone an artist? I don’t think is has anything to do with a paintbrush. There are painters who follow the numbers, or paint billboards, or work in a small village in China, painting reproductions. These folks, while swell people, aren’t artists. On the other hand, Charlie Chaplin was an artist, beyond a doubt. So is Jonathan Ive, who designed the iPhone. You can be an artist who works with oil paints or marble, sure. But there are artists who work with numbers, business models, and customer conversations. Art is about intent and communication, not substances.

An artist is someone who uses bravery, insight, creativity, and boldness to challenge the status quo. And an artist takes it personally.

That’s why Bob Dylan is an artist, but an anonymous corporate hack who dreams up Pop 40 hits on the other side of the glass is merely a marketer. That’s why Tony Hsieh, founder of Zappos, is an artist, while a boiler room of telemarketers is simply a scam.

Tom Peters, corporate gadfly and writer, is an artist, even though his readers are businesspeople. He’s an artist because he takes a stand, he takes the work personally, and he doesn’t care if someone disagrees. His art is part of him, and he feels compelled to share it with you because it’s important, not because he expects you to pay him for it.

Art is a personal gift that changes the recipient. The medium doesn’t matter. The intent does.

Art is a personal act of courage, something one human does that creates change in another.”

“The tragedy is that society (your school, your boss, your government, your family) keeps drumming the genius part out. The problem is that our culture has engaged in a Faustian bargain, in which we trade our genius and artistry for apparent stability.”

“The problem with competition is that it takes away the requirement to set your own path, to invent your own method, to find a new way.”

“A brilliant author or businesswoman or senator or software engineer is brilliant only in tiny bursts. The rest of the time, they’re doing work that most any trained person could do.”

“The greatest shortage in our society is an instinct to produce. To create solutions and hustle them out the door. To touch the humanity inside and connect to the humans in the marketplace.”

“The competitive advantages the marketplace demands is someone more human, connected, and mature. Someone with passion and energy, capable of seeing things as they are and negotiating multiple priorities as she makes useful decisions without angst. Flexible in the face of change, resilient in the face of confusion. All of these attributes are choices, not talents, and all of them are available to you.”