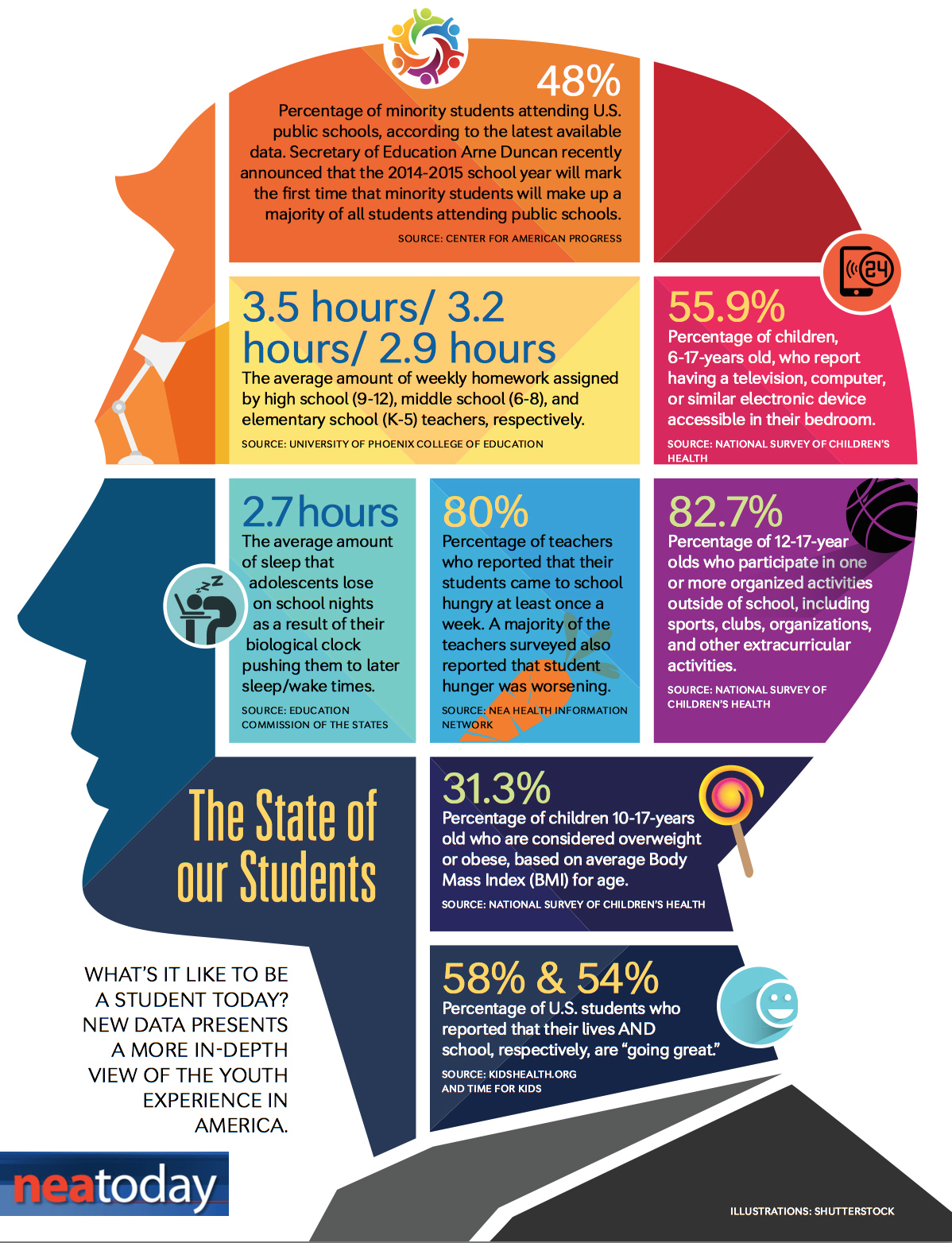

When students and teachers learn together about how their brains influence behavior, one expert says, discipline can become less of a confrontation and more of a partnership

It was the Friday morning before spring break, and Deanna Nibarger’s fifth-graders were noisily chatting and enjoying their breakfast of milk, granola bars and raisins when a woman’s voice crackled over the school intercom:

“Sit up straight and close your eyes,” the woman on the intercom said.

The room immediately went silent as the woman’s command was followed by a series of short, high-pitched “dings,” as if someone were hitting a key on a metal xylophone and letting the sound reverberate.

A trance settled over the class for nearly a minute. Then, the daily morning announcements resumed, and the class sprang back to life as everyone stood to say the Pledge of Allegiance.

Rarely do such moments of calm appear in elementary school classrooms, but it’s exactly this kind of focus that Crooked Creek Elementary School in Washington Township is looking to build in its students. The dings over the intercom are one example of ways teachers at the school have armed students with meditation-like practices to help increase focus and attention.

It might sound strange, but in a fast-paced classroom, teachers at Crooked Creek say just having their students close their eyes and listen for a minute can help them improve their ability to focus. It’s part of the school’s efforts to incorporate the tenets of the growing academic field known as “educational neuroscience” into the classroom.

The field of educational neuroscience is at the intersection of cognitive psychology, education and neuroscience, and some of its teachings suggest findings from brain research can be applied to classroom management and discipline techniques.

Some trend toward the area of “mindfulness,” such as attempting to sharpen students’ focus through meditation. Other facets of the field that Crooked Creek teachers employ in the classroom include taking short breaks from instruction to ward off boredom and teaching children explicitly about parts of the brain and how they respond to stress.

Crooked Creek has been working with teacher and college professor Lori Desautels to help infuse elements of educational neuroscience into the classroom.

Desautels isn’t just teaching brain science to the teachers. She’s also helping children understand how their own brains work to in an effort to help them learn to change their behavior.

The educational neuroscience field is in flux, and some of its teachings — especially ones that directly tie student learning outcomes to brain science — still leave neuroscientists skeptical. But that’s not at the core of what Desautels is doing in Indianapolis schools. Rather, it’s about using what experts know about the brain to build stronger relationships and classroom culture.

“We are in a new time in education,” said Desautels, who works with teachers and students in several Indianapolis schools. “We hear about reform every day in the paper. We read it, we hear it in the news, but what’s really at the crux of all of this is educational neuroscience. Students are learning about their own neuroanatomy, and they are loving it.”

A growing field

Researchers have been exploring how brain science and education work together for about 50 years, but Desautels said the field has recently morphed into something new that is taking off across the country and outside the U.S.

“It’s a brand-new discipline that is catching on fire right now,” Desautels said.

The idea is to introduce both teachers and students to a basic understanding of how the brain works. If teachers have an idea of what’s going on behind the bad behavior, they can more effectively reach their students because they know it might not just be a child choosing to be defiant or difficult. When students know how parts of their brains work, they might better understand why they might feel frustrated or aggressive. That can help them develop strategies to lower stress so they can work to improve behavior in the future.

“Neuroanatomy knowledge eases their stress because they know they are not alone and can have control over that,” Desautels said.

Deanna Nibarger leads her class in a “morning meeting” where they can check in with each other and build relationships as a class.

The exact relationship between the how the brain works and how kids learn — and how teachers should teach — isn’t fully fleshed out, said Lise Eliot, a neuroscience professor from Chicago Medical School and Rosalind Franklin University.

“The so-called ‘neuroscience of education”… it’s not ready for prime time yet,” Eliot said. “There are a lot of very good neuroscientists who are interested in translating our understanding to how our brain learns to better educational practices, but I would say that at this point, improvements in educational practice have come only from the behavioral level.”

And that’s mainly where Desautel’s work lies — in using new strategies and information to improve behavior. The methods are especially relevant as schools look to correct disparities in instances of school discipline. Indiana, like many places across the country, has acknowledgedracial differences in the way that suspensions, expulsions and other punishments are meted out.

Nibarger, the fifth-grade teacher from Crooked Creek, had a background in special education and behavior management before she ever met Desautels. The year she came to Washington Township just happened to be the first year Desautels piloted her approach with the Crooked Creek fifth-graders.

Since she started working with Desautels three years ago, she’s seen school culture begin to change, and she’s more sure of her own teaching. The very first year of the pilot, no students were suspended, and school office referrals decreased, she said.

Understanding what her kids’ brains might be going through during moments of stress or frustration has helped Nibarger make sense of a lot of disparate classroom management concepts she’d already learned.

“It has kind of affirmed a lot of what I already knew to be best practice,” she said. “When people asked me what I was doing for behavior, I didn’t have research or knowledge to do that. Now I know why I do what I do.”

Educational neuroscience, Desautels said, is the intersection of cognitive psychology, education and neuroscience. The element of it that encourages building relationships through better understanding of how emotions and stress impact the brain informs some of the philosophies behind discipline strategies becoming popular in the U.S, she said.

At Crooked Creek, Nibarger has taken the lessons to heart and uses them on a daily basis.

“If you were to come to room 18, we talk a lot about emotions being contagious.” Nibarger said. “We do morning meetings, and we talk through conflict. I teach the kids about neuroplasticity; their brains being able to change because of their experiences in life.”

Using brain knowledge to better behavior

One of the first things Desautels teaches students and teachers is “the 90-second rule,” which admittedly has a much larger following in psychological circles than neuroscientific ones.

“Our body rinses clear and clean of negative emotion in 90 seconds,” she said. “Why do we stay irritated for so long? We keep thinking about it, replaying it and generating more negative emotions.”

The premise is championed by Harvard-educated brain researcher Jill Bolte Taylor, who essentially says the chemicals that course through the brain during a stressful experience dissipate after 90 seconds. Eliot said she wasn’t familiar with the concept. But while emotional recovery time is likely different from person to person, the point, Desautels said, is to let kids know they can have a hand in controlling their emotions.

Things don’t always run smoothly in classrooms, between teachers and students or between kids themselves — conflict is inevitable. But rather than focusing on just being reactive, Desautels said, teachers and students can arm themselves with strategies early on so moments of stress don’t turn into meltdowns.

There are three key ways to de-escalate a conflict that are known to reduce stress as well: movement, time and breathing.

When kids can release energy by moving around, take some time away from the stressful moment or just breathe, Desautels said, they can calm down and actually think about what’s going on around them. Otherwise, they stay stressed out and might lash out more, she said.

The same goes for teachers — those strategies can ease their tension so they can respond constructively to a student. Desautels recommends asking these questions: What do you need? How can I help? What can we do to make this better?

“Consequences don’t need to be immediate,” Desautels said. “That, neurobiologically, is the worst thing we can do.”

When the brain is under stress, Desautels said, the part that controls problem-solving, logic, planning and organizing — known as the “prefrontal cortex” — isn’t getting enough blood and oxygen. Instead, all the blood is heading to the amygdala, the part of the brain responsible for emotion. That’s why feeling upset might make a child yell or hit before it makes them sit back and talk a problem through. Plus, the prefrontal cortex is one of the last parts of the brain to develop, so children are already more likely to respond emotionally to stress than adults.

“We have to prime the brain for discipline and learning before we can do anything else,” Desautels said. “Unless we teach the behaviors that we want to see, many times emotional regulation, which is what negative behavior is all about, it’s not there. And we just assume everybody is born having great ability to emotionally regulate.”

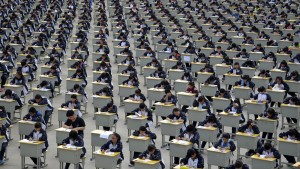

Fifth-graders at Crooked Creek Elementary School in Washington Township eat breakfast before their morning announcements.

Teaching neuroscience to kids isn’t quite as hard as it sounds — First, they’ll start with model that lets them learn each part of the brain and what it does.

In Nibarger’s class, it’s clear the teaching has taken hold. Her students use words and phrases like “neurons” and “brain trauma” in regular classroom conversation. On the day before spring break, she asked them to tell her what happens when you have “hidden anger.”

Almost immediately, one boy piped up. He said a lack of sleep can cause trauma in the brain that blocks synapses from firing, which mean the brain works more slowly. Another girl said keeping anger to yourself means you can’t connect well to your friends.

“If you don’t talk about it and get it out of your system, you get frustrated and isolated,” she said.

Aside from the three basic strategies of movement, time and breathing, Desautels encourages teachers to use “brain breaks” to keep kids from drifting off during class.

“The brain pays attention to novelty,” Desautels said. “It’s a good way to change up because the brain is lulled to sleep with routine.”

A brain break could be almost anything — kids can get up and balance on one foot or play coordination games that ask them to hold out both hands and switch between making an “L” with one hand and a Sign Language “I” with the other. Or, it can be chimes on the intercom to give children a moment of calm in the morning.

Using the brain breaks and attention exercises throughout the school day not only helps kids shake things up if they need to refocus, but they are strategies they can turn to in times of stress.

The approach isn’t magic — managing behavior can still be slow-going, Desautels said, especially if kids become aggressive and don’t yet trust their teachers.

One third-grade class she’s working in this year at Washington Township’s Greenbriar Elementary School is particularly challenging — many of the students come from low-income families, and some have parents in jail.

Sometimes, they’ll yell or swear or even knock over a desk. Desautels said that can be typical for students constantly living in a state of stress, but the class is making progress. She encourages teachers to carve out areas of their classrooms where kids can go to take a break and calm down. Teachers at the school are partnered with each other so they have extra hands if one needs to the leave the classroom with the student or contact a parent.

How to deal with frequently disruptive, or even violent, students is a question common to most all classroom management or discipline techniques. There isn’t an easy answer Desautels said — it takes time for teachers and students to build trust. Incorporating aspects of educational neuroscience can help ensure that when confrontation does happen, frustration and rash decisions aren’t king.

“For teachers who say it’s too gentle, I say absolutely not,” Desautels said. “What we have to do is set up those procedures and transitions and boundaries, and the hardest part is we have to stay connected emotionally to those students during the worst of conflicts.

And regardless of the particular field you’re in, Eliot said, that connection piece is paramount to success in the classroom.

“What we know about human brain function is that it can’t be divorced from social environment,” Eliot said. “The more teachers appreciate how crucial that is to have healthy positive, nurturing relationships and extensive bonding and connecting and mentoring of their students, the more successful they’ll be, the healthier their students will be and the better they’ll learn.”