In his piece, he attacked the logic of teaching around multiple intelligences and pointed to some of the research that shows that tailoring learning opportunities to common assumptions around visual, auditory, and other such supposed learning styles are not good ways of teaching different students.

A problem with Loveless’s argument is that many of my fellow “disruptors” and I who think that it is important to disrupt the education system think this way not under the mindset that it will—or should—help with multiple intelligences or learning styles, but instead because of a simpler and more rigorously tested notion that is far less ideological than Loveless assumes.

Today’s factory-model education system, which was built to standardize the way we teach, falls short in educating successfully each child for the simple reason that just because two children are the same age, it does not mean they learn at the same pace or should follow the same pathway. Each child has different learning needs at different times.

Although academics, including cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, and education researchers, have waged fierce debates about what these different needs are—some talk about multiple intelligences and learning styles whereas others point to research that undermines these notions—what no one disputes is that each student learns at a different pace. Some students learn quickly. Others learn more slowly. And each student’s pace tends to vary based on the subject or even concept one is learning. The reason for these differences, in short, is twofold.

First, everyone has a different aptitude—or what cognitive scientists refer to as “working memory” capacity, meaning the ability to absorb and work actively with a given amount of information from a variety of sources, including visual and auditory. Second, everyone has different levels of background knowledge—or what cognitive scientists refer to as “long-term memory.” What this means is that people bring different experiences or prior knowledge into any learning experience, which impacts how they will learn a concept. If a teacher assumes that everyone in a class is familiar with an example from history that is only ancillary to the point of a particular lesson, for example, but uses that example to illustrate a particular point, then the students who are unfamiliar with the example or who have misconceptions about that example, may just miss the point of the lesson or develop misconceptions about the point of the lesson itself. This isn’t under dispute.

There is also widespread agreement that, as a result, targeting learning just above a student’s level such that it is not too easy or hard is critical to helping students be successful (Daniel Willingham, who Loveless cites in his discussion debunking the learning-style theory, writes extensively about this in his book Why Don’t Students Like School—in the first chapter). If Loveless had kept up with our writing (not that I blame him for not) or read Disrupting Class with a bit more of a nuanced eye, he would have seen that we didn’t pin our argument on multiple intelligences or learning styles per se—we were quite up front that we are not experts in the learning sciences by any means. Instead, we asserted broadly that students had varying learning needs and used learning styles as a device to illustrate the point. Mea culpa on using that example, as I’ve written more extensively here, but at the same time, it doesn’t refute the fundamental point of our argument that customization—or personalization—is needed if we are to help every child reach his or her fullest potential.

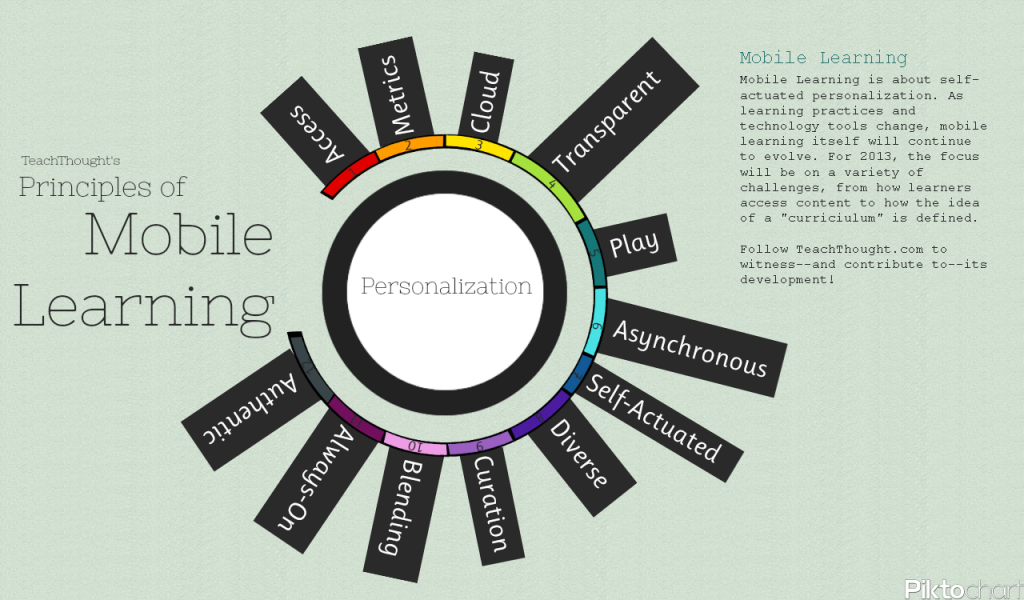

Understanding this helps us understand the logic of personalizing learning and moving away from the current system that mandates the amount of time students spend in class, but does not expect each child to master learning. Because our education system is built to standardize, not personalize, transforming it through disruptive innovation is critical.

This seems to play into one of Loveless’s core worries though, as he seems to have a love for some of the assumptions embedded in the factory model of education. As he wrote, “Moreover, individualized instructional programs, whether delivered exclusively online or through ‘blended’ regimes, are antithetical to the goal that all students learn a common body of knowledge and skills at approximately the same time.” The challenge, of course, with his argument is that today students do not in fact learn or master a common body of knowledge and skills at approximately the same time; they are merely taught them—which is far different from truly learning them.

Why is Loveless concerned about students learning the same thing at the same time? First, because learning some things in common, he says, are important. I agree. Learning some things in common—of course not all things, but a strong foundation—is important. Again, although I am no expert, the research suggests that a strong foundation of knowledge is critical for future learning and meaningful participation in and contribution to society (but it’s also not sufficient, which is why developing deeper skills and dispositions are so important—a false either-or from which we need to move away). This isn’t antithetical to blended or student-centered learning; if Loveless thinks it is, I recommend he visit one of the KIPP LA elementary schools. What he sees might surprise.

Second, Loveless assumes that because students may learn these things at different times in a blended-learning world, that it will exacerbate the achievement gap—a legitimate worry. We need more research here, but the evidence seems to suggest that the achievement gap is exacerbated in the factory-model system when a student does not master a concept, develops holes in her learning, and the teacher just moves on to the next concept the next day. Instead, what we’ve seen in Chugach, Alaska and elsewhere, is that when we move to a competency-based learning system concerned with rigor—in which students move on to new concepts only upon mastery (and there exists the notion of a minimum pace so students who are falling behind get more attention and gaps don’t grow too big)—that students who would typically be left behind and see their gaps grow bigger and bigger, instead experience a sea change when misconceptions are corrected, they master foundational knowledge and skills, and they can then accelerate much faster than anyone would have expected.

Different students also struggle at different points. Who struggles and where is often unpredictable ahead of time—in other words, “the smart kids” group and “the slow kids” group aren’t fixed. Will competency-based learning exacerbate some gaps? Certainly. The most talented students—who we under-serve and hold back today—will be able to accelerate even faster. The hope though is that these gaps will have less to do with race and wealth than they do today, but we don’t know for sure. We do know though that the status quo factory-model system—in my mind the opposite of a student-centered one—is failing along this dimension.

I’ve also heard Loveless attack personalized learning, one of the two components of what I think of as making up a student-centered education system (the other being competency-based education). Loveless looked up studies that purported to be implementing “personalized” learning and found that the approaches weren’t necessarily effective.

The challenge though is in assuming once again that everyone means the same thing by the term or did the same sorts of interventions; simply looking up personalized learning in the peer-reviewed research is too simplistic.

There are lots of notions and differing definitions of what personalized learning is, but when I, and many other disruptors use the phrase, we mean learning that is tailored to an individual student’s particular needs—in other words, it is customized or individualized to help each individual succeed. The power of personalized learning, understood in this way, is intuitive. When students receive one-on-one help from a tutor instead of mass-group instruction, the results are generally far superior. This makes sense, given that tutors can do everything from adjusting if they are going too fast or too slow to rephrasing something a different way or providing a different example or approach to make a topic come to life for a student.

But you don’t have to take our word for it. Studies show the power of this kind of personalized learning for maximizing student success. Benjamin Bloom’s classic “2 Sigma Problem” study, published in 1984, measured the effects of students learning with a tutor to deliver personal, just-in-time, customized help. The striking finding was that by the end of three weeks, the average student under tutoring was about two standard deviations above the average of the control class. That means that the average tutored student scored higher than 98 percent of the students in the control class.

Furthermore, 90 percent of the tutored students attained the level of summative achievement reached by only the highest 20 percent of the students under conventional instructional conditions. A more recent meta-analysis by Kurt VanLehn that revisits Bloom’s conclusion suggests that the effect size of human tutoring seems to be more around 0.79 standard deviations than the widely publicized 2 standard deviation figure. But even with this revision, the impact is hugely significant. The problem is that having a human tutor for each student is prohibitively expensive; so to educate large numbers of students in the early 1900s, we adopted the factory model of education we have today. The logic behind blended learning is that we can gain the benefits of mass customization—many of the effects of a personal tutor in other words—without the costs.

Now, of course, as we implement blended learning, we may learn new things about how learning works. The opportunity to collect empirical data in near real time will be far greater, so we can test out different approaches for different students and see what works, for whom, and under what circumstances. And as we do so, perhaps we’ll learn that learning styles—not the simplistic notion we have today, but, as Jose Ferreira, CEO of Knewton wrote, “that different ways of learning certain concepts are more or less productive for certain students”—do indeed exist.

But we don’t have to believe that will happen for us to believe in personalized, competency-based, blended, or student-centered learning. Of course, perhaps we do need a better vocabulary to express what we mean.

Michael Horn is Executive Director of Education at The Clayton Christensen Institute, the co-author of “Disrupting Class.” He’s a graduate of Yale University and Harvard Business School. This post first appeared on Forbes.com and Wired Academic; Image attribution flickr user flickeringbrad