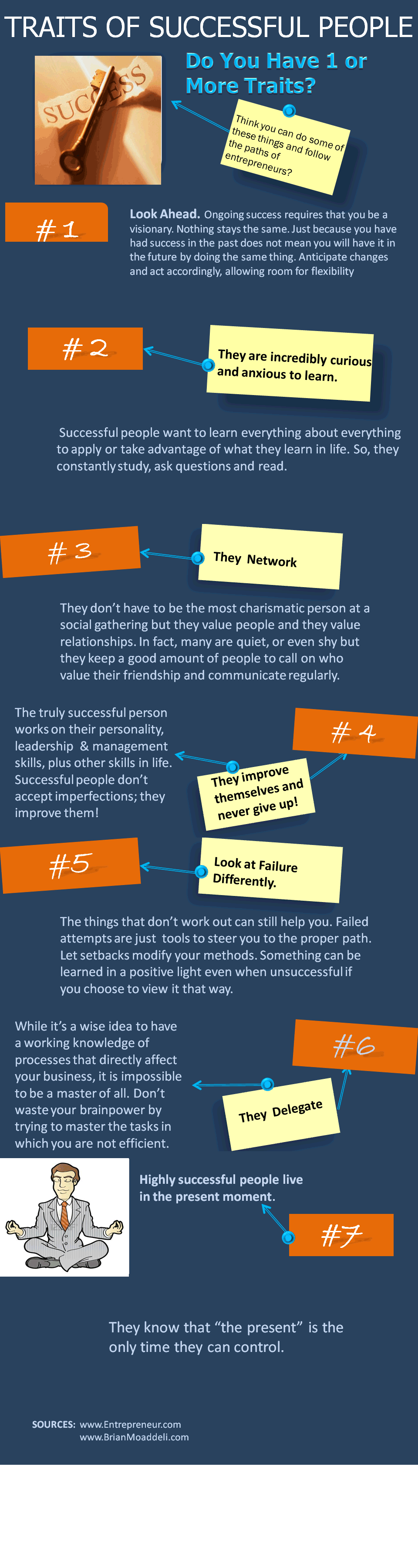

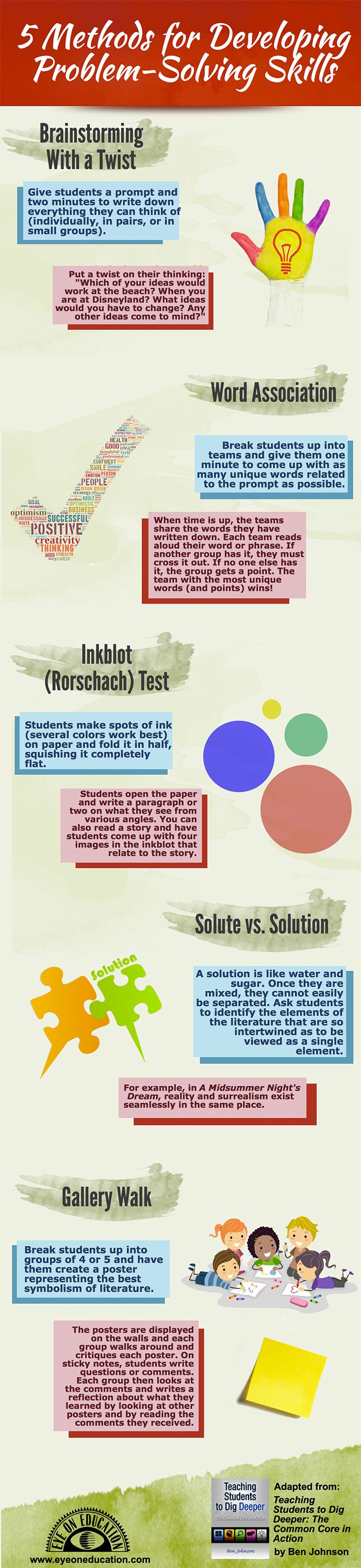

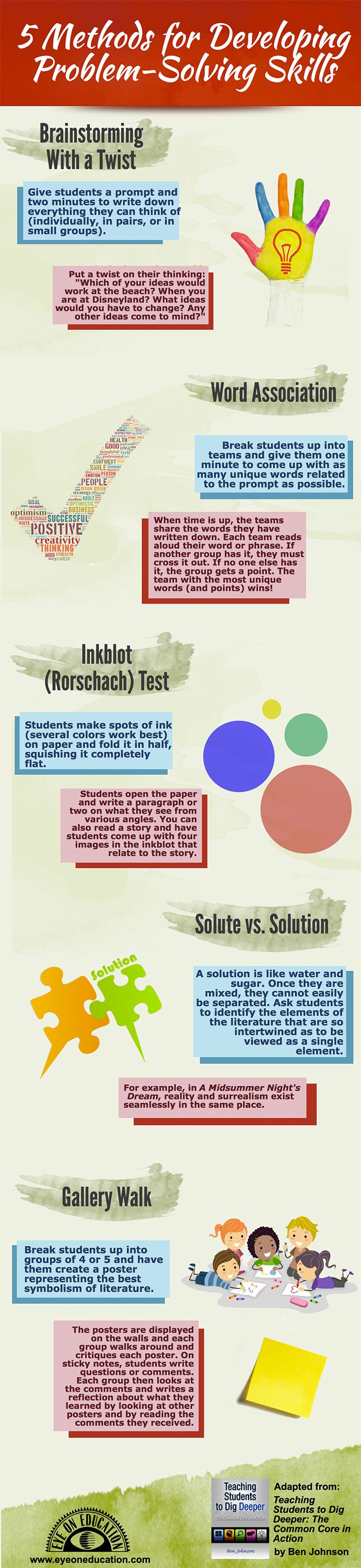

5 Methods for Developing Problem Solving Skills

Marvell Robinson was in kindergarten when a classmate reportedly poured an anthill on him at the playground. After that, the gibes reportedly became sharper: “Why are you that color?” one boy taunted at the swing set, leaving Marvell scared and speechless. The slow build of racial bullying would push his mother, Vanessa Robinson, to pull him from his public school and homeschool him instead.

Marvell is one of an estimated 220,000 African American children currently being homeschooled, according to the National Home Education Research Institute. Black families have become one of the fastest-growing demographics in homeschooling, with black students making up an estimated 10 percent of the homeschooling population. (For comparison’s sake, they make up 16 percent of all public-school students nationwide, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.)

And while white homeschooling families traditionally cite religious or moral disagreements with public schools in their decision to pull them out of traditional classroom settings, studies indicate black families are more likely to cite the culture of low expectations for African American students or dissatisfaction with how their children—especially boys—are treated in schools.

Marvell, now 7 and in the second grade, was the only black student in both his kindergarten and first-grade classes, and one of only a few black students in his San Diego elementary school, according to his mother. And Marvell’s Asperger syndrome—a high-functioning form of autism that makes social interaction difficult—only added to the curiosity and cruelty with which his fellow classmates approached him, Robinson added. She was concerned the school wasn’t doing enough about it. “I just thought maybe I could do a better job myself,” she said.

“They said, ‘kids will be kids,’ and the only solution was for Marvell to be monitored—like he had done something wrong,” Robinson said. “In the end, I don’t think that anyone should have to monitor my kid” because of other kids’ behavior.

Robinson allowed Marvell to finish first grade there and began homeschooling him when he started second grade in September. Robinson adjusted her nursing schedule to include 12-hour shifts on the weekends so she could take on educating Marvell during the week. Her husband, a sous chef at a restaurant in downtown San Diego, continues to work full-time and participates in lessons when he can.

And while her primary motivation was giving Marvell individualized attention, Robinson was unable to separate her worries about racial bullying from the decision. “If he hadn’t been bullied I would have really looked into transferring schools, or going back to where I grew up in Kansas,” she said. “At least in Kansas it was more racially diverse. I assumed that’s how the schools would be in San Diego, but I was wrong.”

Robinson likely joins hundreds of other African American parents who’ve decided to homeschool their children because of dissatisfaction with the traditional campuses. Indeed, Joyce Burges at National Black Home Educators has watched her membership grow “exponentially” in the 15 years since the organization was founded, a trend also reflected in Marvell’s home state of California. While Burges’s national conferences in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, used to attract only around 50 people, they now attract upwards of 400, she said—a noteworthy number for the first organization for black homeschoolers in a sea of predominantly white organizations.

Research conducted by Marie-Josée Cérol—known professionally as Ama Mazama—also offers insight into the growing trend. A faculty member in the African American Studies department at Temple University in Philadelphia, Mazama began homeschooling her three children 12 years ago and realized quickly that there was little research on black homeschoolers.

“Whenever there are mentions of African American homeschoolers, it’s assumed that we homeschool for the same reasons as European-American homeschoolers, but this isn’t really the case,” she said. “Because of the unique circumstances of black people in this country, there is really a new story to be told.”

In a 2012 report published in the Journal of Black Studies, Mazama surveyed black homeschooling families from around the country and found that most chose to educate their children at home at least in part to avoid school-related racism. Mazama calls this rationale “racial protectionism” and said it is a response to the inability of schools to meet the needs of black students. “We have all heard that the American education system is not the best and is falling behind in terms of international standards,” she said. “But this is compounded for black children, who are treated as though they are not as intelligent and cannot perform as well, and therefore the standards for them should be lower.”

Mazama said schools also rob black children of the opportunity to learn about their own culture because of a “Euro-centric” world-history curriculum. “Typically, the curriculum begins African American history with slavery and ends it with the Civil Rights Movement,” she said. “You have to listen to yourself simply being talked about as a descendent of slaves, which is not empowering. There is more to African history than that.” Mazama’s studies show that black parents who choose to homeschool often teach a comprehensive view of African history by incorporating more detailed descriptions of ancient African civilizations and accounts of successful African people throughout history. This allows children to “build their sense of racial pride and self esteem,” she said.

Meanwhile, Cheryl Fields-Smith, an associate professor in the department of Educational Theory and Practice at the University of Georgia, has in her own studies found similar motivations among black homeschoolers. “The schools want little black boys to behave like little white girls, and that’s just never going to happen. They are different,” she said. “I think black families who are in a position to homeschool can use homeschooling to avoid the issues of their children being labeled ‘trouble makers’ and the suggestion that their children need special-education services because they learn and behave differently.”

What it means to be “in a position to homeschool” has long been a question in the homeschooling community. According to Mazama, regardless of race, homeschooling families tend to be wealthier and better educated because they must have the economic ability to have one parent stay home full time. Home education, she added, is “not a middle-class phenomenon.”

However, both Mazama and Fields-Smith say this is beginning to change; barriers that in the past might have left homeschooling out of the question for many working-class families are being lifted. Greater access to public-education resources is making homeschooling more appealing, too. Mazama pointed to the availability of subsidies ensuring homeschooled children have access to standard public-school nutritional offerings, for example, and public programs allowing homeschooled students to enroll in extracurricular activities and after-school sports as reasons why families are increasingly seeing homeschooling as a valid alternative to traditional education. In fact, Fields-Smith is in the process of writing a book on black, single homeschooling mothers because she sees “more and more families of less means” making the decision to sacrifice traditional career paths so that they can pull their children from school.

Rhonda McKnight would be an archetypical candidate for Fields-Smith’s book. As a single mother, she works about 45 hours per week as a contractor for the state of Georgia—often at odd hours and during the weekend—so she can homeschool her 8-year-old son, Micah. “It’s not easy,” McKnight said. “It’s extremely difficult to balance everything.” While a common criticism of homeschooling is a potential lack of socialization for children, Mazama said the growing number of homeschooling groups solves this problem. McKnight for her part joined a homeschooling collective that, in addition to providing Micah time with other children, also helps her manage her workload. The group gathers on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays to engage in extracurricular and hands-on learning activities that can’t easily be done in the home, giving McKnight some time to herself—and, of course, some time to work.

Micah, who like Marvell is autistic, didn’t learn well in a classroom with 25 students. McKnight also felt as though his teacher was misinterpreting the symptoms of his disability as behavioral problems and accusing him of “behavior that was not typical to him.” “I don’t know how racially motivated it was at the time,” McKnight said. “But even black teachers are taught certain things they are not even aware of. Our culture tends towards labeling our boys.”

The poor education, according to McKnight, left Micah significantly behind in several subjects, which means she’s now trying to pack as much into his schedule as possible to get him back on track. “He doesn’t really get a day off—not right now, because he’s just behind. I feel like he doesn’t really have time to relax,” McKnight said, explaining she wasn’t aware just how behind he was until she started to homeschool him. Most devastating, she said, was when she realized her son was reading well below his expected third-grade level: “I felt like I had totally failed him, and the school had totally failed him, and the only thing I could do was work with him one-on-one to get him caught up.”

To get Micah up to par in his academics, McKnight has employed a customized mix of purchased homeschool lesson plans and learning materials she developed herself—all on top of what he learns at the collective. When Micah is home, McKnight said her days are “totally dedicated to him.” They work for at least an hour on each of the core subjects, studying within the grade level that best suits him in each area. On days he returns from the collective, McKnight reads with him for two or three hours with the goal of getting him to a third-grade level by the end of the year. Lessons even continue on Saturdays and Sundays. He’s at his father’s place every other weekend, where he continues his reading schedule, and on the weekends that he’s home McKnight takes him on educational field trips—Atlanta’s many museums are frequent destinations.

It’s this ability to shape everyday activities and lessons to meet the personal needs of each child that Fields-Smith finds so promising about homeschooling—especially for black families. “There is no one way to homeschool,” she said, noting all of the families that she consulted for her study were “catering to their children and customizing their education for them” instead of using a single stock homeschooling curriculum.

Still, Mazama and Fields-Smith acknowledge that homeschooling is controversial, particularly in the black community. “For African Americans there is a sense of betrayal when you leave public schools in particular,” Mazama said. “Because the struggle to get into those schools was so harsh and so long, there is this sense of loyalty to the public schools. People say, ‘We fought to get into these schools, and now you are just going to leave?’”

For Paula Penn-Nabrit, an African American scholar and writer who homeschooled her children in the 1990s, this struggle hits very close to home. Her husband’s uncle, James Nabrit, argued Brown v. Board of Education in front of the Supreme Court alongside Thurgood Marshall; he later served as the president of Howard University. When Penn-Nabrit decided to pull her three sons from public school, it angered many of her black friends. “A lot of people felt that because my family was intimately involved in the effort to integrate schools, that for me to pull my children out of schools was a betrayal of all that work,” she said. “But it really wasn’t. The case had nothing to do with what I, as a parent, decide I want for my child. That decision meant the state can’t decide to give me less than, but I can decide I want more than.”

In 2003, Penn-Nabrit published a book, Morning by Morning: How We Home-Schooled Our African-American Sons to the Ivy League, in an effort to help others repeat her successes with homeschooling. Her older twin sons, Damon and Charles, both attended Princeton, and her youngest son, Evan, went to Amherst College and then to the University of Pennsylvania.* The book, according to Penn-Nabrit, received “a lot of open hostility”—with several people accusing her of racism—because it detailed accounts of the discrimination her sons allegedly faced in public school and emphasized an Afrocentric approach to education.

Upon deciding to homeschool their sons, Penn-Nabrit and her husband, both of whom have degrees in the humanities, elected to teach them the subject areas they knew well.** For the remaining science and math courses, however, they hired black, mostly male, graduate students from the Ohio State University to take over—in large part so that the boys had exposure to successful people who looked like them.*** After all, according to the Department of Education, less than 2 percent of current classroom teachers nationwide are African American males; until their homeschooling, Penn-Nabrit’s children had never had a black man as a teacher.

“Most black people go to school and never have a teacher that looks like them, and this is particularly true for black boys,” she said. Similar concerns, she noted, led to the creation of single-sex schools—a particularly apt comparison for Penn-Nabrit, who attended Wellesley. “If women benefit from having a period of isolation from the larger group, that could be applicable to black boys as well.”

Mazama, meanwhile, said that rooting children in their heritage in an educational setting allows them to do better emotionally and socially. “If anything, homeschooled black children would be much stronger because they would not have been devastated at an early age by racism,” she said. She explained that the absence of these early destructive experiences, combined with a heritage-focused curriculum, ultimately allows children to recognize and deal constructively with racism—”not by denying it, but by confronting it because they are comfortable with who they are.”

“That’s the way I teach my own children,” she continued. “I have seen this work.”

Back in San Diego, Vanessa Robinson has also seen it work. Now that she’s been homeschooling Marvell for five months, she notices that he is better adjusted and has moved farther along academically than he did in public school.

“He’s a completely different person,” she said, reporting that his confidence is higher compared to where it was in public school, allowing him to make friends in his neighborhood and learn more quickly. Robinson said that, while she bought a set of lesson plans with a suggested timeline, Marvell now moves so quickly that she has to add lessons together from an array of instructional programs just to keep up. And when he finds something he loves, she lets him dive deep. “Right now, Marvell says he wants to work for NASA, so we’re really focusing on getting in depth into science and space,” she said. His new interest is a thrilling prospect for Robinson, a registered nurse with a background in science.

“I just want my son to be a free thinker and to question everything,” she said. “I wish that when I was growing up, I could have done that.”

* This post previously stated that both of Paula Penn-Nabrit’s sons graduated from Princeton with honors. We regret the error.

** This post previously stated that Penn-Nabrit’s husband had an advanced degree in the humanities. We regret the error.

*** This post previously stated that the graduate students Penn-Nabrit hired to instruct her sons attended the University of Ohio. We regret the error.

This story was produced in collaboration with The Hechinger Report.

via Mindshift

Excerpt from Thinking Through Project-Based Learning: Guiding Deeper Inquiry, published by Corwin, 2013.

When students engage in quality projects, they develop knowledge, skills, and dispositions that serve them in the moment and in the long term. Unfortunately, not all projects live up to their potential. Sometimes the problem lies in the design process. It’s easy to jump directly into planning the activities students will engage in without addressing important elements that will affect the overall quality of the project.

With more intentional planning, we can design projects that get at the universal themes that have explicit value to our students and to others. We can design projects to be rigorous, so students’ actions mirror the efforts of accomplished adults. They will feel the burn as they learn and build up their fitness for learning challenges to come.

There are several ways to start designing projects. One is to select among learning objectives described in the curriculum and textbooks that guide your teaching and to plan learning experiences based on these. Another is to “back in” to the standards, starting with a compelling idea and then mapping it to objectives to ensure there is a fit with what students are expected to learn. The second method can be more generative, as any overarching and enduring concept is likely to support underlying objectives in the core subject matter and in associated disciplines, too. Either way you begin, the first step is to identify a project-worthy idea.

We have condensed the project design process into six steps. After outlining the steps briefly below, we offer examples that show how one might use these steps to develop a germ of an idea into a project plan that emphasizes inquiry. Read the steps and examples all the way through before digging in to your own plan.

Ask yourself: What important and enduring concepts are fundamental to the subjects I teach? Identify four or five BIG concepts for each subject.

Now, think: Why do these topics or concepts matter? What should students remember about this topic in 5 years? For a lifetime? Think beyond school and ask: In what ways are they important and enduring? What is their relevance in different people’s lives? In different parts of the world? Explore each concept, rejecting and adding ideas until you arrive at a short list of meaningful topics.

Look back to three or four concepts you explored and think about real-life contexts. Who engages in these topics? Who are the people for whom these topics are central to their work? See if you can list five to seven professions for each concept.

With that done, now think: What are the interdisciplinary connections? In what ways might the topic extend beyond my subject matter? For example, if your subject specialty was math and you imagined an entrepreneur taking a product to market, the central work might involve investment, expense, and profit analyses. The project might also involve supply chains and transportation (geography), writing a prospectus for a venture capitalist (language arts), and designing a marketing campaign (language arts, graphic design, technology).

As you begin to imagine these topics in the context of a project, ask yourself, what might you ask of students? How might you push past rote learning into investigation, analysis, and synthesis? Consider how you can engage critical thinking in a project by asking students to:

Now, step back and write a project sketch—or two or three. For each, give an overview of the project. Describe the scenario and the activities students are likely to engage in. Anyone reading it should be able to tell what students will learn by doing the project. The process of writing will help you refine your ideas. There are dozens of project sketches in this book (and all are included in the Project Library in the Appendix). Use them as a guide.

Three small but useful elements are left, and together with the project sketch, they provide a framework for the project. Write a title, entry event, and driving question for your project.

Project title. A good title goes a long way toward anchoring the project in the minds of your school community. A short and memorable title is best.

Teachers at Birkdale School in New Zealand take their projects seriously. They not only provide them with proper names but also fly a special flag in the school’s entry when a new project begins. You might not need to go this far, but a good title conveys a sense of importance and helps make a project memorable. Let these project titles inspire you.

Entry event. Plan to start off the project with a “grabber,” a mysterious letter, jarring “news,” a provocative video, or other attention-getting event. As we discussed in Chapter 4, make sure it is novel (to make students alert) and has emotional significance (to make them care). Read these examples and imagine how your students might respond. Then plan an entry event for your project.

Driving question. Kick off your project with a research question students will feel compelled to investigate. Imagine a driving question that leads to more questions, which, in their answering, contribute to greater understanding. Good questions grab student interest (they are provocative, intriguing, or urgent), are open ended (you can’t Google your way to an answer), and connect to key learning goals.

Consider how to write a good question based on these “remodeled” examples (Larmer, 2009):

Workshop your project idea, especially at steps 5 and 6. Colleagues, students, parents, and subject matter experts will ask questions that will clarify your thinking and contribute ideas you might not have considered.

For more about the book, check out Suzie Boss’s ISTE presentation.