Untangling your organization’s decision making

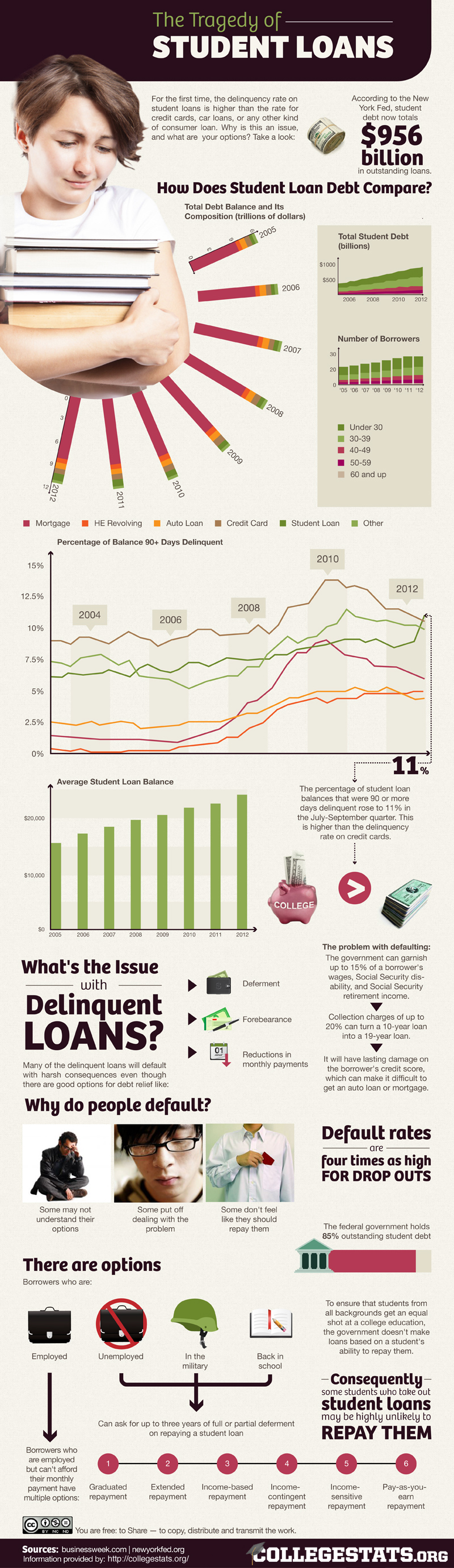

Now for the bad news. In many large global companies, growing organizational complexity, anchored in strong product, functional, and regional axes, has clouded accountabilities. That means leaders are less able to delegate decisions cleanly, and the number of decision makers has risen. The reduced cost of communications brought on by the digital age has compounded matters by bringing more people into the flow via email, Slack, and internal knowledge-sharing platforms, without clarifying decision-making authority. The result is too many meetings and email threads with too little high-quality dialogue as executives ricochet between boredom and disengagement, paralysis, and anxiety (Exhibit 1). All this is a recipe for poor decisions: 72 percent of senior-executive respondents to a McKinsey survey said they thought bad strategic decisions either were about as frequent as good ones or were the prevailing norm in their organization.

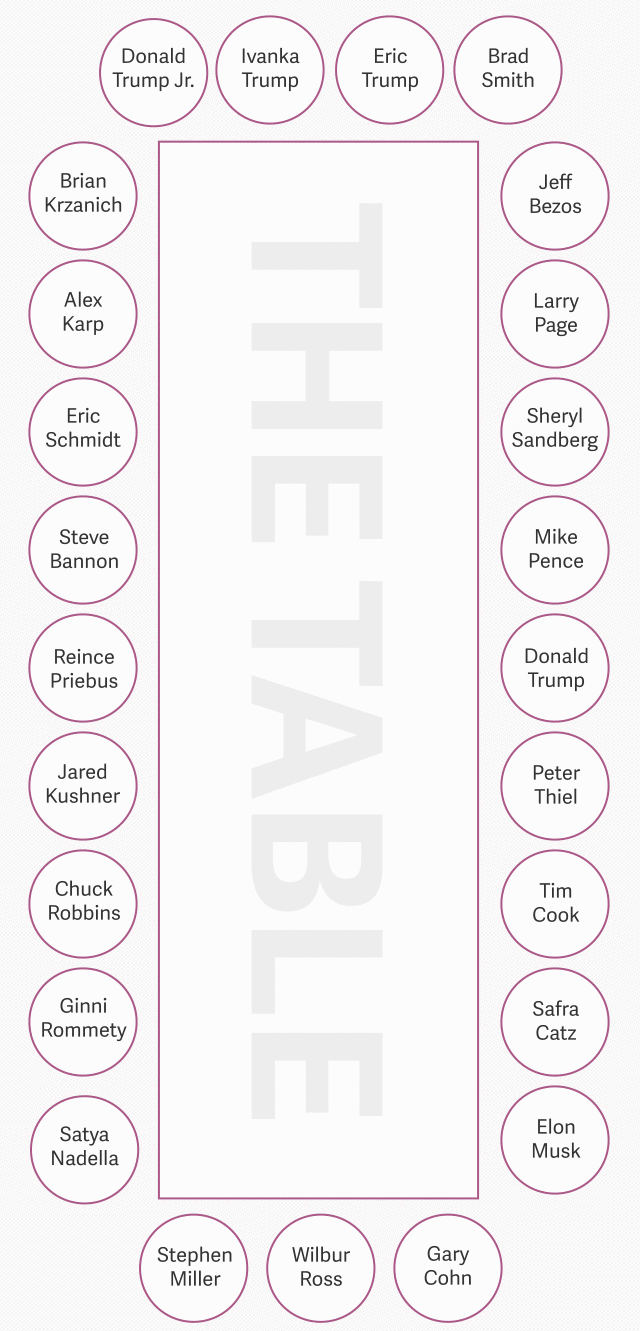

The ultimate solution for many organizations looking to untangle their decision making is to become flatter and more agile, with decision authority and accountability going hand in hand. High-flying technology companies such as Google and Spotify are frequently the poster children for this approach, but it has also been adapted by more traditional ones such as ING (for more, see our recent McKinsey Quarterly interview “ING’s agile transformation”). As we’ve described elsewhere, agile organization models get decision making into the right hands, are faster in reacting to (or anticipating) shifts in the business environment, and often become magnets for top talent, who prefer working at companies with fewer layers of management and greater empowerment.

As we’ve worked with organizations seeking to become more agile, we’ve found that it’s possible to accelerate the improvement of decision making through the simple steps of categorizing the type of decision that’s being made and tailoring your approach accordingly. In our work, we’ve observed four types of decisions (Exhibit 2):

- Big-bet decisions. These infrequent and high-risk decisions have the potential to shape the future of the company.

- Cross-cutting decisions. In these frequent and high-risk decisions, a series of small, interconnected decisions are made by different groups as part of a collaborative, end-to-end decision process.

- Delegated decisions. These frequent and low-risk decisions are effectively handled by an individual or working team, with limited input from others.

- Ad hoc decisions. The organization’s infrequent, low-stakes decisions are deliberately ignored in this article, in order to sharpen our focus on the other three areas, where organizational ambiguity is most likely to undermine decision-making effectiveness.

These decision categories often get overlooked, in our experience, because organizational complexity, murky accountabilities, and information overload have conspired to create messy decision-making processes in many companies. In this article, we’ll describe how to vary your decision-making methods according to the circumstances. We’ll also offer some tools that individuals can use to pinpoint problems in the moment and to take corrective action that should improve both the decision in question and, over time, the organization’s decision-making norms.

Before we begin, we should emphasize that even though the examples we describe focus on enterprise-level decisions, the application of this framework will depend on the reader’s perspective and location in the organization. For example, what might be a delegated decision for the enterprise as a whole could be a big-bet decision for an individual business unit. Regardless, any fundamental change in decision-making culture needs to involve the senior leaders in the organization or business unit. The top team will decide what decisions are big bets, where to appoint process leaders for cross-cutting decisions, and to whom to delegate. Senior executives also serve the critical functions of role-modeling a culture of collaboration and of making sure junior leaders take ownership of the delegated decisions.

Big bets

Bet-the-company decisions—from major acquisitions to game-changing capital investments—are inherently the most risky. Efforts to mitigate the impact of cognitive biases on decision making have, rightly, often focused on big bets. And that’s not the only special attention big bets need. In our experience, steps such as these are invaluable for big bets:

- Appoint an executive sponsor. Each initiative should have a sponsor, who will work with a project lead to frame the important decisions for senior leaders to weigh in on—starting with a clear, one-sentence problem statement.

- Break things down, and connect them up. Large, complex decisions often have multiple parts; you should explicitly break them down into bite-size chunks, with decision meetings at each stage. Big bets also frequently have interdependencies with other decisions. To avoid unintended consequences, step back to connect the dots.

- Deploy a standard decision-making approach. The most important way to get big-bet decisions right is to have the right kind of interaction and discussion, including quality debate, competing scenarios, and devil’s advocates. Critical requirements are to create a clear agenda that focuses on debating the solution (instead of endlessly elaborating the problem), to require robust prework, and to assemble the right people, with diverse perspectives.

- Move faster without losing commitment. Fast-but-good decision making also requires bringing the available facts to the table and committing to the outcome of the decision. Executives have to get comfortable living with imperfect data and being clear about what “good enough” looks like. Then, once a decision is made, they have to be willing to commit to it and take a gamble, even if they were opposed during the debate. Make sure, at the conclusion of every meeting, that it is clear who will communicate the decision and who owns the actions to begin carrying it out.

An example of a company that does much of this really well is a semiconductor company that believes so much in the importance of getting big bets right that it built a whole management system around decision making. The company never has more than one person accountable for decisions, and it has a standard set of facts that need to be brought into any meeting where a decision is to be made (such as a problem statement, recommendation, net present value, risks, and alternatives). If this information isn’t provided, then a discussion is not even entertained. The CEO leads by example, and to date, the company has a very good track record of investment performance and industry-changing moves.

It’s also important to develop tracking and feedback mechanisms to judge the success of decisions and, as needed, to course correct for both the decision and the decision-making process. One technique a regional energy provider uses is to create a one-page self-evaluation tool that allows each member of the team to assess how effectively decisions are being made and how well the team is adhering to its norms. Members of key decision-making bodies complete such evaluations at regular intervals (after every fifth or tenth meeting). Decision makers also agree, before leaving a meeting where a decision has been made, how they will track project success, and they set a follow-up date to review progress against expectations.

Big-bet decisions often are easy to recognize, but not always (Exhibit 3). Sometimes a series of decisions that might appear small in isolation represent a big bet when taken as a whole. A global technology company we know missed several opportunities that it could have seized through big-bet investments, because it was making technology-development decisions independently across each of its product lines, which reduced its ability to recognize far-reaching shifts in the industry. The solution can be as simple as a mechanism for periodically categorizing important decisions that are being made across the organization, looking for patterns, and then deciding whether it’s worthwhile to convene a big-bet-style process with executive sponsorship. None of this is possible, though, if companies aren’t in the habit of isolating major bets and paying them special attention.

Cross-cutting decisions

Far more frequent than big-bet decisions are cross-cutting ones—think pricing, sales, and operations planning processes or new-product launches—that demand input from a wide range of constituents. Collaborative efforts such as these are not actually single-point decisions, but instead comprise a series of decisions made over time by different groups as part of an end-to-end process. The challenge is not the decisions themselves but rather the choreography needed to bring multiple parties together to provide the right input, at the right time, without breeding bureaucracy that slows down the process and can diminish the decision quality. This is why the common advice to focus on “who has the decision” (or, “the D”) isn’t the right starting point; you should worry more about where the key points of collaboration and coordination are.

It’s easy to err by having too little or too much choreography. For an example of the former, consider the global pension fund that found itself in a major cash crunch because of uncoordinated decision making and limited transparency across its various business units. A perfect storm erupted when different business units’ decisions simultaneously increased the demand for cash while reducing its supply. In contrast, a specialty-chemicals company experienced the pain of excess choreography when it opened membership on each of its six governance committees to all senior leaders without clarifying the actual decision makers. All participants felt they had a right (and the need) to express an opinion on everything, even where they had little knowledge or expertise. The purpose of the meetings morphed into information sharing and unstructured debate, which stymied productive action (Exhibit 4).

Whichever end of the spectrum a company is on with cross-cutting decisions, the solution is likely to be similar: defining roles and decision rights along each step of the process. That’s what the specialty-chemicals company did. Similarly, the pension fund identified its CFO as the key decision maker in a host of cash-focused decisions, and then it mapped out the decision rights and steps in each of the contributing processes. For most companies seeking enhanced coordination, priorities include:

- Map out the decision-making process, and then pressure-test it. Identify decisions that involve a cross-cutting group of leaders, and work with the stakeholders of each to agree on what the main steps in the process entail. Lay out a simple, plain-English playbook for the process to define the calendar, cadence, handoffs, and decisions. Too often, companies find themselves building complex process diagrams that are rarely read or used beyond the team that created them. Keep it simple.

- Run water through the pipes. Then work through a set of real-life scenarios to pressure-test the system in collaboration with the people who will be running the process. We call this process “running water through the pipes,” because the first several times you do it, you will find where the “leaks” are. Then you can improve the process, train people to work within (and, when necessary, around) it, and confront, when the stakes are relatively low, leadership tensions or stresses in organizational dynamics.

- Establish governance and decision-making bodies. Limit the number of decision-making bodies, and clarify for each its mandate, standing membership, roles (decision makers or critical “informers”), decision-making protocols, key points of collaboration, and standing agenda. Emphasize to the members that committees are not meetings but decision-making bodies, and they can make decisions outside of their standard meeting times. Encourage them to be flexible about when and where they make decisions, and to focus always on accelerating action.

- Create shared objectives, metrics, and collaboration targets. These will help the persons involved feel responsible not just for their individual contributions in the process, but also for the process’s overall effectiveness. Team members should be encouraged to regularly seek improvements in the underlying process that is giving rise to their decisions.

Getting effective at cross-cutting decision making can be a great way to tackle other organizational problems, such as siloed working (Exhibit 5). Take, for example, a global finance company with a matrix of operations across markets and regions that struggled with cross-business-unit decision making. Product launches often cannibalized the products of other market groups. When the revenue shifts associated with one such decision caught the attention of senior management, company leaders formalized a new council for senior executives to come together and make several types of cross-cutting decisions, which yielded significant benefits.

Delegated decisions

Delegated decisions are far narrower in scope than big-bet decisions or cross-cutting ones. They are frequent and relatively routine elements of day-to-day management, typically in areas such as hiring, marketing, and purchasing. The value at stake for delegated decisions is in the multiplier effect they can have because of the frequency of their occurrence across the organization. Placing the responsibility for these decisions in the hands of those closest to the work typically delivers faster, better, and more efficiently executed decisions, while also enhancing engagement and accountability at all levels of the organization.

In today’s world, there is the added complexity that many decisions (or parts of them) can be “delegated” to smart algorithms enabled by artificial intelligence. Identifying the parts of your decisions that can be entrusted to intelligent machines will speed up decisions and create greater consistency and transparency, but it requires setting clear thresholds for when those systems should escalate to a person, as well as being clear with people about how to leverage the tools effectively.

It’s essential to establish clarity around roles and responsibilities in order to craft a smooth-running system of delegated decision making (Exhibit 6). A renewable-energy company we know took this task seriously when undergoing a major reorganization that streamlined its senior management and drove decisions further down in the organization. The company developed a 30-minute “role card” conversation for each manager to have with his or her direct reports. As part of this conversation, managers explicitly laid out the decision rights and accountability metrics for each direct report. This approach allowed the company’s leaders to decentralize their decision making while also ensuring that accountability and transparency were in place. Such role clarity enables easier navigation, speeds up decision making, and makes it more customer focused. Companies may find it useful to take some of the following steps to reorganize decision-making power and establish transparency in their organization:

- Delegate more decisions. To start delegating decisions today, make a list of the top 20 regularly occurring decisions. Take the first decision and ask three questions: (1) Is this a reversible decision? (2) Does one of my direct reports have the capability to make this decision? (3) Can I hold that person accountable for making the decision? If the answer to these questions is yes, then delegate the decision. Continue down your list of decisions until you are only making decisions for which there is one shot to get it right and you alone possess the capabilities or accountability. The role-modeling of senior leaders is invaluable, but they may be reluctant. Reassure them (and yourself) by creating transparency through good performance dashboards, scorecards, and key performance indicators (KPIs), and by linking metrics back to individual performance reviews.

- Avoid overlap of decision rights. Doubling up decision responsibility across management levels or dimensions of the reporting matrix only leads to confusion and stalemates. Employees perform better when they have explicit authority and receive the necessary training to tackle problems on their own. Although it may feel awkward, leaders should be explicit with their teams about when decisions are being fully delegated and when the leaders want input but need to maintain final decision rights.

- Establish a clear escalation path. Set thresholds for decisions that require approval (for example, spending above a certain amount), and lay out a specific protocol for the rare occasion when a decision must be kicked up the ladder. This helps mitigate risk and keeps things moving briskly.

- Don’t let people abdicate. One of the key challenges in delegating decisions is actually getting people to take ownership of the decisions. People will often succumb to escalating decisions to avoid personal risk; leaders need to play a strong role in encouraging personal ownership, even (and especially) when a bad call is made.

This last point deserves elaboration: although greater efficiency comes with delegated decision making, companies can never completely eliminate mistakes, and it’s inevitable that a decision here or there will end badly. What executives must avoid in this situation is succumbing to the temptation to yank back control (Exhibit 7). One CEO at a Fortune 100 company learned this lesson the hard way. For many years, her company had worked under a decentralized decision-making framework where business-unit leaders could sign off on many large and small deals, including M&A. Financial underperformance and the looming risk of going out of business during a severe market downturn led the CEO to pull back control and centralize virtually all decision making. The result was better cost control at the expense of swift decision making. After several big M&A deals came and went because the organization was too slow to act, the CEO decided she had to decentralize decisions again. This time, she reinforced the decentralized system with greater leadership accountability and transparency.

Instead of pulling back decision power after a slipup, hold people accountable for the decision, and coach them to avoid repeating the misstep. Similarly, in all but the rarest of cases, leaders should resist weighing in on a decision kicked up to them during a logjam. From the start, senior leaders should collectively agree on escalation protocols and stick with them to create consistency throughout the organization. This means, when necessary, that leaders must vigilantly reinforce the structure by sending decisions back with clear guidance on where the leader expects the decision to be made and by whom. If signs of congestion or dysfunction appear, leaders should reexamine the decision-making structure to make sure alignment, processes, and accountability are optimally arranged.

None of this is rocket science. Indeed, the first decision-making step Peter Drucker advanced in “The effective decision,” a 1967 Harvard Business Review article, was “classifying the problem.” Yet we’re struck, again and again, by how few large organizations have simple systems in place to make sure decisions are categorized so that they can be made by the right people in the right way at the right time. Interestingly, Drucker’s classification system focused on how generic or exceptional the problem was, as opposed to questions about the decision’s magnitude, potential for delegation, or cross-cutting nature. That’s not because Drucker was blind to these issues; in other writing, he strongly advocated decentralizing and delegating decision making to the degree possible. We’d argue, though, that today’s organizational complexity and rapid-fire digital communications have created considerably more ambiguity about decision-making authority than was prevalent 50 years ago. Organizations haven’t kept up. That’s why the path to better decision making need not be long and complicated. It’s simply a matter of untangling the crossed web of accountability, one decision at a time.

By Aaron De Smet, Gerald Lackey, and Leigh M. Weiss

Image Credit:

Image Credit: