How Edtech Tools Evolve Introduction: We’ve Heard This Before

CHAPTER THREE

How Edtech Tools Evolve

Introduction: We’ve Heard This Before

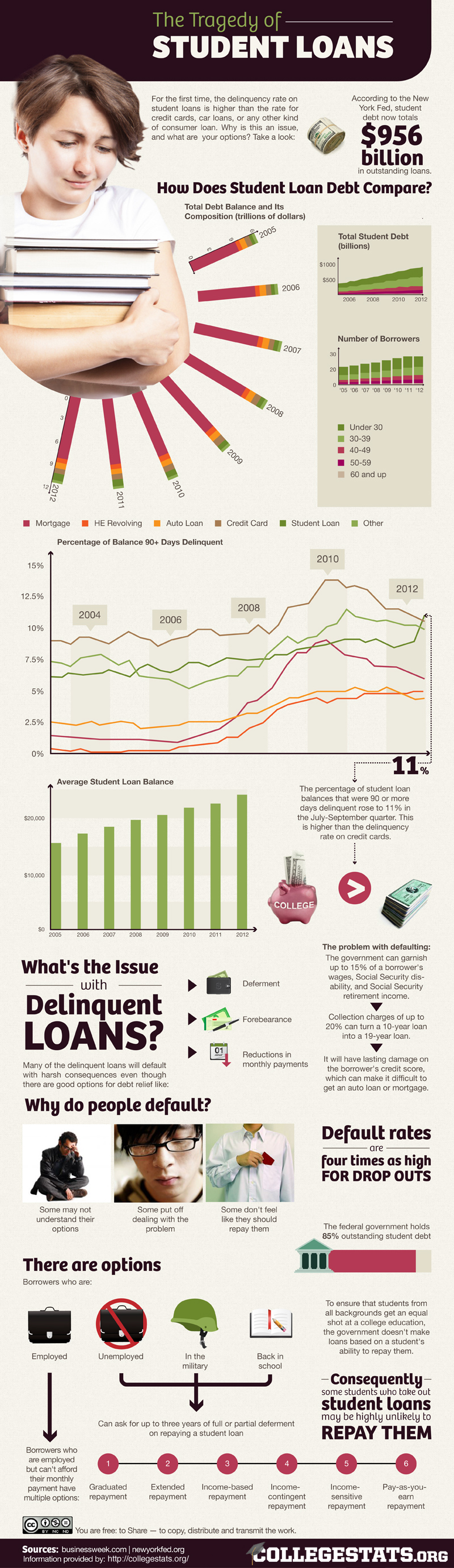

Great inventors have proclaimed technology’s potential to transform education before. In 1913, Thomas Edison asserted that “books will soon be obsolete in the public schools,” replaced by motion pictures. Nearly a century later, Steve Jobs, according to his biographer Walter Isaacson, believed print textbooks were “ripe for digital destruction.”

Not so fast. Over the decades, a parade of technologies—television, “teaching machines,” interactive whiteboards and desktop computers—seemed to have a far more muted impact on learning than futurists and entrepreneurs predicted. Even the trusty wood-pulp book still soldiers on: Roughly half of district IT leaders surveyed by the Consortium for School Networking believe that print materials will still be used regularlyby 2018.

“The pattern of hype leading to disappointment, leading to another cycle of overpromising with the next technology, has a long history to it,” notes Larry Cuban, an education professor at Stanford University who began his career as a high school history teacher in the 1950s.

And yet, puncturing this bleak scenario are shining examples of times when technology has made a difference. In North Carolina, educators at Mooresville Graded School District (hailed by The New York Times as the “de facto model of the digital school” in 2012) attribute a boost in test scores, attendance and graduation rates to the smart use of laptops and online software (earning itself the title). In rural Central California, Lindsay Unified School District’s ongoing efforts to refine its competency-based learning model has led to small bumps in test scores—but a dramatic drop in truancy, suspension and gang membership rates.

So what’s the difference? When can technology have a galvanizing effect, rather than amplify existing educational practices?

Kentaro Toyama, a professor at University of Michigan’s School of Information, has often observed the latter. How can new practices extend beyond just a single class or a hero teacher, but for a community, and on a sustained basis? What portion of the answer lies with technology—and what portion with how it’s used?

The pattern of hype leading to disappointment, leading to another cycle of overpromising with the next technology, has a long history to it.

—Larry Cuban, emeritus professor at Stanford University

This chapter of our year-long survey of the role of technology in education dives into technology’s contribution to that fragile equation. And arguably one of the most thoughtful perspectives on technology’s role in education comes from Ruben Puentedura, a former teacher and university media center director. His investigation into the role of technology in education in the late 1980s led to an observation that was simultaneously clear-eyed yet profound: Not every device or app can or should transform how teachers teach.

To wield technology well, Puentedura asserts, teachers must ask and answer: “What opportunities does new technology bring to the table that weren’t available before?” Puentedura codified his observations in a framework nicknamed “SAMR,” which offers an invaluable window into understanding the different ways that technology can support changes in instructional practices and learning outcomes.

Yet there is a non-negotiable requirement for technology to make a difference. It has to work without requiring herculean workarounds.

Sometimes the lynchpin requirements are technical. Electric cars were infeasible without lithium batteries and lightweight composites. Sometimes the requirements also involve structural issues. Digital readers and e-books first came to market in 1998, but it took nearly a decade to resolve problems around limited memory and storage, title selections, copyright, conflicting file formats and other technical issues before e-books captured significant consumer market share.

For educators to be able to count on technology, it has to work with the reliably of a lightswitch. And for decades, it has not. Justeight percent of all computers in U.S. public schools had internet access in 1995. A decade later, that figure jumped to 97 percent—yet only 15 percent of all public schools enjoyed wireless connection. Software incompatibility and technical problems, such as creating and managing accounts, proved problematic for educators. Nearly half of the educators surveyed in 2008 by the National Education Association reported feeling adequately prepared to integrate technology into instruction. Fewer than one-third used computers to plan lessons or teach.

In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will.

—Rudiger Dornbusch, MIT economics professor

Today, more than 77 percent of U.S. school districts offer bandwidth speeds of 100 kbps per student for accessing online resources. This, coupled with cloud computing services that allow apps, services and data to be accessed and shared on the web, have made technology much more feasible for use. The marketplace for online educational tools has also grown; Apple’s store now boasts more than 80,000 such apps. Interoperability standards are beginning to ease how data from different schools systems and instructional tools are stored and shared. From 2013 to 2015, U.S. K-12 schools purchased more than 23 million devices, according to Futuresource Consulting.

“In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will,” Rudiger Dornbusch, the late MIT economics professor, once said, “and then they happen faster than you thought they could.”

Today’s education technology has matured after decades of fits and starts. Improved bandwidth, cloud computing power and distribution channels such as app stores, among other infrastructural improvements, have helped developers make technologies more accessible, affordable and, most importantly, reliable for students and teachers to use.

Yet the question remains: What will technology do once it is in the hands of teachers and students? To better understand the interplay of new technologies and instructional practices, we’ll explore how edtech tools in three popular categories—math, English Language Arts and assessment—have evolved over time, how they reflect the pedagogical trends and then what this means in the context of Puentedura’s framework.

How are these products changing?

To better understand how instructional practices have transformed, we’ll explore how the capabilities of tools

Product Profiles: What Today’s Tools Offer

SAMR: Is Technology Making the Difference?

Case Studies: From Technology to Practice

Product Profiles: What Today’s Tools Offer

How have today’s technologies evolved to help children develop math and reading abilities—the two core competencies that typically reflect how well they’re learning in school? And how do new tools allow them to demonstrate what they know, aside from traditional paper-and-pencil tests?

Math

In Search of the Middle Ground

“Who gets to learn mathematics, and the nature of the mathematics that is learned, are matters of consequence.”

Alan Schoenfeld, UC Berkeley Math Professor

Is it more important for kids to memorize math formulas and compute—or understand concepts and create their own approaches to solving problems? Whether students use pencils or iPads, the question has long stirred impassioned discussion among parents, teachers, mathematicians and policymakers. In 2004 University of California, Berkeley math professor, Alan Schoenfeld, described this debate as “Math Wars” that have persisted throughout the 20th century.

Disagreements persist today between “traditionalists” who believe math instruction should focus on calculations and processes, versus “reformers” who want students to develop the logical and conceptual understanding behind math. The “New Math” movement of the 1950s, championed by professional mathematicians, attempted to introduce conceptual thinking, such as the ability to calculate in bases other than 10. (Below is a satirical song by pianist and mathematician Tom Lehrer.) The effort floundered, derided by parents, teachers and mathematicians who lampooned the instruction as overly abstract and conceptual.

A 2007 report from the National Mathematics Advisory Panel, assembled by the U.S. Department of Education, summed up these battles as a struggle over:

“How explicitly children must be taught skills based on formulas or algorithms (fixed, 2 step-by-step procedures for solving math problems) versus a more inquiry-based approach in which students are exposed to real-world problems that help them develop fluency in number sense, reasoning, and problem-solving skills. In this latter approach, computational skills and correct answers are not the primary goals of instruction.”

This polarization is “nonsensical,” Schoenfeld noted. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive. Why can’t math instruction embrace both procedural and conceptual knowledge?

The Common Core math standards, released in June 2010, is the latest attempt to find a middle ground. Originally adopted by 46 states, the standards aim to pursue “conceptual understanding, procedural skills and fluency, and application with equal intensity.” Yet some students, parents and teachers have heckled the standards for befuddling homework problems and tests. It seemed not even curriculum developers knew how to translate Common Core math principles into instructional materials. See one example of a math problem gone “viral.” Concerns about “fuzzy math” resurfaced, amplified through social media channels and YouTube.

Yet one fundamental difference between the math wars today and those of a half century ago is that today’s technology—in the form of Google or software such as Wolfram Alpha—can solve nearly any math problem with clicks and swipes. This ability will influence what teachers teach and how those subjects are taught.

“Math has been liberated from calculating,” proclaimes Conrad Wolfram, strategic director of Wolfram Research. Computers, he states, can allow students to “experience harder problems [and be] able to play with the math, interact with it, feel it. We want people who can feel the math instinctively.”

How Math Tools Evolved

From Drilling to Adapting

The earliest instructional math software didn’t offer much in the form of instruction. In 1965, Stanford University professor Patrick Suppes led one of the first studies on how a text-based computer program could help fourth-grade students achieve basic arithmetic fluency. The program displayed a problem and asked students to input an answer. Correct responses would lead to the next problem, while incorrect ones would prompt a “wrong” message and give students another chance to get the correct answer. If this second attempt was still incorrect, the program would show the correct answer, and repeat the problem to help reinforce the facts.

Credit: Number Munchers (left) and Math Blaster (right)

Decades later, many instructional math software would retain the same “drill-and-kill” approach. This trend was best reflected in the popularity of games such as Number Munchers and Math Blaster in late ’80s and throughout the ’90s, which also incorporated gaming elements such as points and rewards into their drill exercises.

Even so, during the 1960s, when enthusiasm for artificial intelligence was on the rise, university researchers began work on “intelligent tutoring systems” aimed at identifying a student’s knowledge gaps and surfacing relevant hints and practice problems. There were limitations, to be sure; researchers lacked enough fine-grain data for their algorithms to make useful inferences. Yet after decades of research, Carnegie Mellon University researchers released one of the first commercially available K-12 educational software programs, Cognitive Tutor. That was followed a year later with ALEKS, based on the work at researchers at University of California, Irvine. The products use different cognitive architecture models to attempt to deduce what a student knows and doesn’t. (To learn more about what happens inside these engines, check out our EdSurge report on adaptive learning edtech products.)

More recently other “adaptive” math tools use frequent assessments to try to pair appropriate content with learners. When a student answers a question incorrectly, such programs attempt to identify knowledge gaps and surface relevant instructional materials. Some tools, like KnowRe, will provide instructions on how to solve a problem. Others tools reinforce procedural concepts in videos that offer instruction ranging from step-by-step explanations (Khan Academy), to animations (BrainPOP), to real-world scenarios (Mathalicious).

Despite the ability of technology to deduce what students need and provide instruction, developers also recognize that educators must still retain their instructional role. DreamBox, which sells adaptive math software, recently added features to allow teachers more control over content assignment. “While we are still really focused on building student agency, we also want to ensure that we build teacher agency,” says Dreambox Chief Executive Officer and President Jessie Woolley-Wilson.

‘Seeing’ Math Beyond Symbols

Everyone uses visual pathways when we work on mathematics and we all need to develop the visual areas of our brains.

—Jo Boaler, education professor at Stanford University

Math is often represented by symbols (+ − x ÷), but technology today allows developers to eschew traditional notations to allow students to explore math in more visual and creative ways. There is supporting evidence: Researchers have observed Brazilian children street vendors performing complex arithmetic calculations through transactions (“street mathematics”) but struggling when presented with the same problems on a formal written test.

“We can make every mathematical idea as visual as it is numeric,” says Stanford education professor and YouCubed co-founder Jo Boaler. Boaler has studied neurobiological research on how solving math problems stimulates areas of the brain associated with visual processing.

“Everyone uses visual pathways when we work on mathematics and we all need to develop the visual areas of our brains,” she wrote in a recent report.

In the 1980s, tools including Geometer’s Sketchpad offered learners ways to explore math visually through interactive graphs. Today’s tools allow teachers to create their own activities and for students to share their work. Desmos, a browser-based HTML5 graphing calculator, invites them to explore and share art made with math equations. “There’s enormous value in allowing students to create, estimate, visualize and generalize,” says Dan Meyer, chief academic officer at Desmos, “but a lot of math software today just allows them to calculate.”

Educational game developers have also found ways to introduce mathematical concepts without using symbols. ST Math (the two letters stand for spatial-temporal), uses puzzles to introduce Pre-K-12 math concepts without explicit language instruction or symbolic notations. Another popular game, DragonBox, lets students practice algebra without any notations. BrainQuake aims to teach number sense through puzzles involving spinning wheels.

Although games can make math more engaging, students may need support from teachers to apply skills learned from the game to schoolwork and tests. “One of the ways video games can be extremely powerful,” says Keith Devlin, a Stanford professor, co-founder and chief scientist of Brainquake and NPR’s “Math Guy,” “is that when a kid has beat a game, he or she may have greater confidence to master symbolic math. I think a two—step approach—video game and teacher—can be key in helping students who hate math get up to speed.”

Source: EdSurge

ELA

Teaching Reading in America

“The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go.”

Dr. Seuss

Like math, literacy has had its own “Reading Wars” (or “Great Debate”) throughout the 20th century. Proponents of a phonics-based approach believed students should learn to decode the meaning of a word by sounding out letters. But in English, not all words sound the way they are spelled, and different words may sound alike. Alternatively, other researchers and educators advocate a “whole language” approach that incorporates reading and writing, along with speaking and listening.

The back-and-forth debate eventually reached policymakers, who were alarmed by the 1983 report, “A Nation at Risk,” that charged that American students were woefully underprepared compared to their international peers. In California, poor results on the 1992 and 1994 National Assessment of Educational Progress reading test—more than half of fourth-grade students were reading below grade level—fueled critiques of the state’s whole-language approach.

In 1997, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development convened a national panel of literacy researchers and educators to evaluate and recommend guidelines. Published in 2000, the report recommended a mix of two approaches, stating that “systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program.” The authors added:

… literacy acquisition is a complex process for which there is no single key to success. Teaching phonemic awareness does not ensure that children will learn to read and write. Many competencies must be acquired for this to happen.

The findings allayed some of the debate over how to teach reading. But the Common Core reading standards raised new questions around what reading materials should be taught, including nonfiction and informational texts that “highlight the growing complexity of the texts students must read to be ready for the demands of college, career, and life.” The standards also aimed to set a higher bar for literacy beyond reading. Students were expected to be able to cite text-specific evidence in argumentative and informational writing.

Yet for all the focus on facts and evidence, the standard writers did not specify what should be read at each grade level. While they offer examples of books appropriate for each grade, states and districts are expected to determine the most appropriate content. In setting high expectations for what students should be able to read, but refraining from offering specific steps to get there, educators wound up left to look for their own resources. This ambiguity has given license to publishers, researchers and entrepreneurs to shape that path.

How ELA Tools Evolved

Source: EdSurge

Tracking Readers

Digital book collections have long promised to expand the availability of fiction and nonfiction books. But now such tools also offer teachers a more convenient way to track reading than reviewing students’ self-recorded logs. Today’s products offer data dashboards that chronicle how many books were read, how long students spent reading and which vocabulary words students looked up. Often digital texts come embedded with questions written by content experts or, in some cases, created by teachers themselves.

Given the capability of tools to capture information about students’ reading habits, it’s “important for teachers to have frameworks and dashboards to make that data actionable,” says Jim O’Neill, chief product officer at Achieve3000. “By having a sense of whether students are comprehending the text, or how much they’ve read, teachers can provide the appropriate follow-up [support].”

Let’s Lexile

The broad scope of available online reading materials makes a traditional challenge even more front and center: How can teachers identify what texts are most appropriate for students? Figuring out the right level of complexity for every student—including subject matter, text complexity, or other factors—is subjective and, at best, an inexact science. Both educators and developers have turned to reading frameworks that attempt to quantify text difficulty by measures such as word length, word count and average sentence length.

“Almost every major edtech literacy company will report on text complexity in some form,” adds O’Neill. A popular framework used by his company and other adaptive literacy products is the Lexile, which measures readers’ comprehension ability and text difficulty on a scale from below 0L (for beginning readers) to over 2000L (advanced) based on two factors: sentence length and the frequency of “rare” words. Many products today will assign students a Lexile score (based on how they perform on assessments after reading a text) and recommend reading content at the appropriate level. Some companies, such asNewsela and LightSail, present the same content rewritten at different Lexile levels so that students can read and discuss the same story.

Despite the popularity of Lexile levels, some researchers such as Elfrieda Hiebert, a literacy educator and chief executive officer ofText Project, preach caution against relying exclusively on Lexile numbers to find grade-appropriate texts. She has pointed out, for instance, that The Grapes of Wrath, a dense book for most high schoolers, has a lower Lexile score (680L) than the early reader book, Where Do Polar Bears Live? (690L). The former has shorter sentences (with plenty of dialogue) while the latter has longer ones.

The Lexile is just one of seven different computer formulas that Common Core standards writers have found to be “reliably and often highly correlated with grade level and student performance-based measures of text difficulty across a variety of text sets and reference measures.” Established companies, including Pearson and Renaissance Learning, have developed alternatives to Lexile. Another effort, the Text Genome Project, which Hiebert is advising, uses machine learning technology to identify and help students learn the 2,500 related word families (such as, help, helpful, helper) that make up the majority of texts they will encounter through high school.

Nod to Nonfiction

The Common Core is not the first effort to emphasize nonfiction and informational texts. In 2009, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) called for a 50-50 split between fiction and nonfiction reading materials for fourth-grade students, and a 30-70 ratio by twelfth grade. Common Core reinforced that message: A 2015 NAEP survey found that the percentage of fourth-grade teachers who used fiction texts “to a great extent” declined from 63 percent to 53 percent between 2011 and 2015, while the nonfiction rose from 36 to 45 percent over the same period.

Source: National Assessment of Educational Progress

Companies have noted this shift and many offer nonfiction content as a selling point. Achieve3000, LightSail Education andNewsela employ both writers who will produce their own nonfiction articles and syndicated stories from news publishers that they rewrite at different Lexile levels. Such content also comes embedded with formative assessments to gauge students’ reading comprehension. Other startups, such as Listenwise, offer audio clips from public radio stations, along with comprehension and discussion questions, to help students build literacy through online listening activities.

Writing to Read

“Writing about a text should enhance comprehension because it provides students with a tool for visibly and permanently recording, connecting, analyzing, personalizing, and manipulating key ideas in text.”

So state the authors of “Writing to Read,” a meta-analysis published in 2010 of 50 years’ worth of studies on the effectiveness of writing practices on students’ reading grades. The need for this skill only grows in the internet era, as students need to be able to comprehend, assess, organize and communicate information from a variety of sources.

According to the Common Core writing standards, students are expected to start writing online by fourth grade, and by seventh grade should be able to “link to and cite sources as well as to interact and collaborate with others.”

Online writing tools—most notably Google Docs, which the company boasts has more than 50 million education users—allow teachers and students to comment and collaborate in the cloud. The industry standard remains MYAccess with patented technology to automatically score papers and provide customized feedback. NoRedInk and Quill offer interactive writing exercises that let students sharpen their technical writing skills and grammar. Other startups, such as Citelighter and scrible scaffold the research and writing process to help students organize their notes and thoughts. Their progress—words written, sources cited, annotations—are captured on a dashboard that teachers can monitor.

Other tools are more ambitious. CiteSmart, Turnitin and WriteLab use natural language processing to provide automatic feedback beyond the typical spelling and grammar checks and attempts to point out errors in logic and clarity. (Our test run with these tools, however, found questionable feedback, suggesting they still need fine-tuning. There are still some core instructional tasks, it turns out, that technology has yet to perfect.)

Assessment

In Search of the Middle Ground

Through embedded assessments, educators can see evidence of students’ thinking during the learning process and provide near real-time feedback through learning dashboards so they can take action in the moment.

2016 National Education Technology Plan

Students find tests stressful for good reason. Results not only evaluate what they have learned, but can be used to determine whether they graduate or get into college. Such assessments are “summative” in that they aim to evaluate what a student has learned at the conclusion of a class. In 2002 when the U.S. government tied school funding to student outcomes through the No Child Left Behind law, tests became stressful for educators as well.

With so much at stake, testing became a top priority in many classrooms. A 2015 survey of 66 districts by the Council of Great City Schools found that U.S. students on average took eight standardized tests every year—which means by the time they graduated high school, they would have taken roughly 112 such tests. Testing fever was followed by fatigue; nearly two-thirds of parents in a Gallup poll released that year said there was too much emphasis on testing.

But tests need not be so punitive. For decades, education researchers have argued that tests can be used during—not after—the learning process. In 1968, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom argued that “formative” assessments could diagnose what a student knew, enabling teachers to adjust their instruction or provide remediation. Students could also use these results to better understand and reflect on what they know.

There’s no emotional stress associated with formative assessments. They help teachers engage with students during the learning process.

—Cory Reid, chief executive officer of MasteryConnect

To check for understanding, teachers can use formative assessments in the form of short quizzes delivered at the beginning or end of class, journal writing and group presentations. (Here are 56 examples.)

“There’s no emotional stress associated with formative assessments,” said Cory Reid, chief executive officer ofMasteryConnect. “They help teachers engage with students during the learning process.”

“In moderation, smart strategic tests can help us measure our kids’ progress in schools [and] can help them learn,” President Obama said in a video address.

“Tests should enhance teaching and learning,” Obama continued. In December 2015, he signed the Every Student Succeeds Act, allowing states more flexibility in determining how and what they could use to assess students. By doing so, the government opened the door to let states decide what works best for their schools.

Summative tests still remain, but the industry has shifted its focus to embedding tests to make them an integral part of the teaching and learning process. In addition academic achievement is no longer the primary focus; technologists are attempting to quantify non-cognitive factors, including student behavior and school culture, all of which impacts how students learn.

How Assessment Tools Evolved

Credit: Vixit/Shutterstock

The Many Forms of Formative Tests

In the 1970s, Scantron Corporation offered one of the most popular and commercially successful technologies for doing formative and summative tests: bubble sheets that students would fill out with #2 pencils that could be automatically graded. A couple decades later, “clickers”—devices with buttons that transmit responses to a computer—offered an even quicker way for teachers and students to get feedback on multiple-choice questions.

Today, web-based and mobile apps can deliver formative assessments and results cheaper and more efficiently. Smartphones and web browsers have become the new clicker to deliver instantaneous feedback. In classrooms where not every student has a computer or a phone, some teachers use apps to snap photos of a printed answer sheet and immediately record grades. And as teachers use more online materials, there are also tools that allow them to overlay questions on text, audio or video resources available on the internet.

Student responses from formative assessment tools can be tied to a teacher’s lesson plans or a school’s academic standards. This information can help teachers pinpoint specific areas where students are struggling and provide targeted support.

Faster feedback also means that assessments can be given even as lessons are going on. “If you know what a student knows when they know it, that informs your instruction as a teacher,” says Reid. That data can “enrich your teaching and help change a student’s path or trajectory.”

Beyond Multiple Choice

The Common Core tests, which many students take on computers, introduced “technology-enhanced items” (TEIs). These allow students to drag-and-drop content, reorder their answers and highlight or select a hotspot to answer questions. Such interactive questions, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s 2016 National Education Technology Plan, “allow students to demonstrate more complex thinking and share their understanding of material in a way that was previously difficult to assess using traditional means,” namely through multiple choice exams.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology, Future Ready Learning: Reimagining the Role of Technology in Education, Washington, D.C., 2016.

A well-designed TEI should let educators “get as much information from how students answer the question in order to learn whether they have grasped the concept or have certain misconceptions,” according to Madhu Narasa, CEO of Edulastic. His company offers a platform that allows educators to create TEIs for formative assessments and helps students prepare for Common Core testing. Another startup, Learnosity, licenses authoring tools to publishers and testing organizations to create question items. (Here are more than 60 different types of TEIs.)

Yet teachers and students need training to use TEIs. And the latest TEIs may not always work on older web browsers and devices. One early version of the Common Core math test developed by Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium featured TEIs that even adults found difficult to use. And, while TEIs offer more interactivity, their effectiveness in measuring student learning remains unproven. A 2015 report from Measured Progress, another developer of Common Core tests, suggested “there is not broad evidence of the validity of inference made by TEIs and the ability of TEIs to provide improved measurement. Without such research, there is no way to ensure that TEIs can effectively inform, guide, and improve the educational process.”

Show Me Your Work

Tests are not the only way for students to demonstrate understanding. Through hands-on projects, students can demonstrate both cognitive and noncognitive skills along with interdisciplinary knowledge. A science fair project, for example, can offer insights into students’ command of science and writing, along with their communication, creativity and collaboration skills.

The internet brought powerful media creation tools—along with cloud-based storage—into classrooms, allowing students to create online. Companies such as FreshGrade offer digital portfolio tools that aim to help students document and showcase their skills and knowledge through projects and multimedia creations in addition to homework and quizzes. Through digital collections of essays, photos, audio clips and videos, students can demonstrate their learning through different mediums.

Games as Test

Credit: SimCity

What can games like SimCity, Plants vs. Zombies and World of Warcraft tell us about problem-solving skills? A growing community of researchers, including Arizona State University professor James Paul Gee, argue that well-designed games can integrate assessment, learning and feedback in a way that engages learners to complete challenges. “Finishing a well-designed and challenging game is the test itself,” he wrote in 2013.

GlassLab, a nonprofit that studies and designs educational games, has developed tools to infer mastery of learning objectives from gameplay data. These tests are sometimes called “stealth assessments,” as the questions are directly embedded into the game. The group has described at length how psychometrics, the science of measuring mental processes, can help game designers “create probability models that connect students’ performance in particular game situations to their skills, knowledge, identities, and values, both at a moment in time and as they change over time.”

A 2014 review of 69 research studies on the effectiveness of games by research group, SRI International, offers supporting evidence that digital game interventions are more effective than non-game interventions in improving student performance. But other studies offer a mixed picture. A study led by Carnegie Mellon University researchers on a popular algebra game, Dragonbox, found that “the learning that happens in the game does not transfer out of the game, at least not to the standard equation solving format.” Similar to the Brazilian “street math” kids (see math profile), these students are capable of solving math problems—just not on a traditional paper exam.

Noncognitive Skills

Educators and researchers also believe that non-cognitive skills—including self-control, perseverance and growth mindset—can deeply influence students’ academic outcomes. In 2016, eight states announced plans to work with the nonprofit CASEL(Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning) to create and implement standards around how social and emotional skills can be introduced into classroom instruction.

Today, developers are seeking ways to quantify factors such as student behavior and school climate. Tools such as Kickboard andLiveSchool record, track and measure student behavior. Panorama Education lets educators run surveys to learn how students, families and staff feel about topics such as school safety, family engagement and staff leadership. Tools like these expand the use of assessments beyond simply measuring student performance on specific subjects and cognitive tasks.

SAMR: How Will We Know If Technology Will Make a Difference?

Will shiny gadgets help educators do the same thing—or enable new modes of teaching and learning? Here’s a popular framework to help us understand how technology can change practice.

No matter what features are built into an edtech product, the technology is unlikely to impact learning if it’s misapplied. “Putting technology on top of traditional teaching will not improve traditional teaching,” said Andreas Schleicher, director for the Directorate of Education and Skills at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, in aninterview with EdSurge earlier this year.

A 2015 report by the OECD found “no appreciable improvements in student achievement in reading, mathematics, or science in the countries that had invested heavily in ICT for education.” Noted Schleicher:

“The reality is that technology is very poorly used. Students sit in a class, copy and paste material from Google. This is not going to help them to learn better.”

But there are several corollaries. First, not every traditional teaching practice needs to be reinvented—some are working well. Second, not every technology can “revolutionize” learning. And third, to get powerful results, the kind that drive student learning, technology must be aligned with practice in purposeful ways.

But first, educators need to know which is which.

As a teaching fellow at Harvard University in the late 1980s, Ruben Puentedura started paying attention to how educators used tools in the classroom. Later, as the director of Bennington College’s New Media Center, he further explored how faculty and students integrated technology and instruction to reach the best learning outcomes. His efforts led him to start a consulting firm, Hippasus, that works with schools and districts to adopt technology.

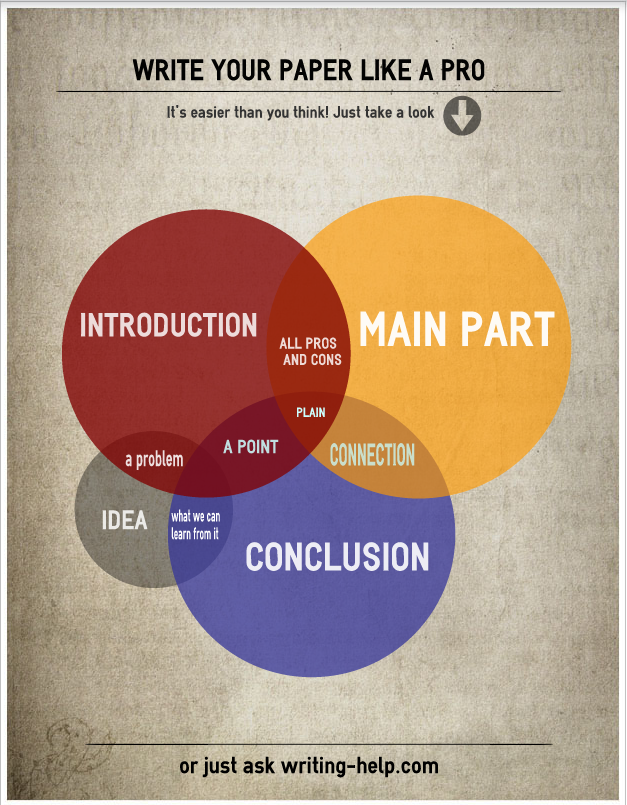

In 2002, he published the SAMR framework to help educators think about how to integrate instructional practice and technology to reach the best outcomes for students. SAMR defines how technology impacts the teaching and learning process in four stages:

S

Substitution

Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with no functional change in instruction

A

Augmentation

Tech acts as a direct tool substitute, with functional improvement

M

Modification

Tech allows for a significant task design

R

Redefinition

Tech allows for the creation of new tasks, previously inconceivable

The SAMR framework is centered around the premise that technology, when used strategically and appropriately, has the potential to transform learning and improve student outcomes. Puentedura has also applied this framework to existing education research to suggest that greater student outcomes can occur when edtech tools are used at the later stages of the framework (modification and redefinition).

Preparing to use SAMR

To start, Puentedura says teachers must be clear about what outcome they want for their students. “The purpose, the goals of teachers, schools and students, are the key drivers in how technology is used,” he says.

“What is it that you see your students not doing that you’d like them to do? What type of knowledge would you like them to explore that they’re not exploring? What type of opportunities for new visions, new ideas, new developments would you like to pick up on?”

Additionally, it is important for teachers to identify how technology is currently used in the classroom, as a reference point for moving through the stages of SAMR. This requires an understanding of available resources—not just the technology that students can access, but also time and support required to use the tools well.

Changes in the tools themselves matter less than how you’re thinking about the learning objectives.

—Jim Beeler, Chief Learning Officer at Digital Promise*

New technologies are often first used at the substitution level, especially when teachers and students are unfamiliar with the tools. This level of usage has its merits, even if it may not radically change instructional practices. Reading digital textbooks may, in the long run, be cheaper for schools than ordering new print versions every time the content is updated. Having students compose essays using a cloud-based word processor makes it easier for teachers to track and grade assignments.

The SAMR framework is not just about technology in and of itself, but rather what educators and students can use the tech to accomplish. “Changes in the tools themselves matter less than how you’re thinking about the learning objectives,” explains Jim Beeler, Chief Learning Officer at Digital Promise, who has helped schools rollout programs where every student has a digital device (called 1:1 programs). After all, the same tool can be used in different stages. A digital textbook, for example, can used as a substitute for print if all students do is read, highlight and annotate. But if the textbook includes speech synthesis or audio features, the students’ reading experience is augmented through the addition of the auditory mode of learning.

A Primer on SAMR

Here are some guiding questions and a familiar type of assignment as an example—sharing reflections on a reading assignment—to better illustrate the SAMR framework in practice.

Ruben Puentedura

Are you going to get more impact upon student outcomes from using technology at the R level than at the S level?

I’m using a technology but I don’t know where I am within the SAMR Framework

Answer the following questions to figure out where you are within the framework

SAMR Misconceptions

Although Puentedura’s studies suggest that greater student outcomes can be achieved at the redefinition level, he warns against the notion that every teacher should aspire to use technology to redefine their practice. “Are you going to get more impact upon student outcomes from using technology at the R level than at the S level? Sure,” he says, “but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t many, in fact, probably a large majority of technology uses that work just fine at the S and A level.”

-

SAMR is just about using technology

SAMR is designed to analyze the intersection of technology and instructional practices. The framework is designed to focus on the changes that technology enables—not the technology itself. Make no mistake—educators and students are the ones that make learning happen, not the technology.

-

It is better to be further “up” the framework

Not every instructional practice needs to be redefined; as Puentedura points out, often “substitution” can be the right form of change. It can be exhausting and inappropriate for teachers and students to constantly teach and learn at the modification and redefinition levels. Educators need to find the right mix of activities that are appropriate for their learning objectives and employ technology in the way that best fits those goals.

-

Change is always necessary

Don’t change just for the sake of change. SAMR—or any other framework—may offer a way to describe changes in technology usage. But that does not mean that teachers should continually strive to change their practices. Teachers must have a clear vision of their instructional goals and desired student outcomes before devising ways to implement new tools in a classroom.

Ruben Puentedura

Can SAMR help schools make smarter purchasing decisions?

Case Studies: From Technology to Practice

Technology can make a difference. Here are a dozen profiles of how educators from across the country have used tools to support instructional needs and transform teaching practices.

S

A

M

R

Math

A Free Tool to Keep a Pulse on Student Learning

SUBSTITUTION + MATH

Addressing the Gaps of All Learners

AUGMENTATION + MATH

Learning Linear Equations in One Week, Not One Year

MODIFICATION + MATH

Playlists That Put Students in Control

REDEFINITION + MATH

ELA

Read All You Want

SUBSTITUTION + ELA

Ditch the Paper. Let’s Make a Podcast!

AUGMENTATION + ELA

90 Second Videos That Inspire Discussion

MODIFICATION + ELA

Taking Reading Assignments To The Next Level

REDEFINITION + ELA

Assessment

Forms for Formative Assessments

SUBSTITUTION + ASSESSMENT

Custom-Built Quizzes For Real-Time Intervention

AUGMENTATION + ASSESSMENT

Formative Assessments Enriched With Data

MODIFICATION + ASSESSMENT

From Paper and Pencil to Real World Assessment

REDEFINITION + ASSESSMENT

Conclusion

Technology is often conflated with innovation. Yet tools are just part of the equation. Innovation entails humans changing behavior.

In education, technological improvements—in the form of faster broadband, devices or smarter data analytics—must be commensurate with the desire to refine and transform existing practices. What these changes look like is unsettled, but technology allows teachers and students to explore different paths.

Well-designed tools can help educators realize the educational “best practices” put forth decades ago by researchers like Benjamin Bloom. Data from formative assessments can give teachers better insights into what each learner needs and change strategies. Games and online collaborative projects allow educators teach in ways that researchers believe can better engage students.

The most useful educational tools are also flexible. Teachers are also adapting media and productivity software for purposes beyond what they were designed for.

After all, what a math class needs may not be online adaptive curriculum, but rather creative tools that allow students to engage and express knowledge in new ways.

Changing ingrained habits and codified practices requires patience. Not all lectures, lesson plans, group projects or homework demand to be uprooted. As our case studies above show, some teachers use technology to do the same tasks more efficiently. Others are creating entirely new activities that transform learning from a solo to social experience.

Whether teachers reinforce or redefine instructional practices with technology partly depends on their environment. Do they have the training to implement new tools? How can schools support teachers in not just experimenting with new methods of teaching and learning—but scale these practices across the campus and district? How can these changes make education opportunities more equitable? These questions will help frame the focus of the next chapter. As classrooms change, so do schools.