“America’s Woeful Public Schools: TIMSS Sheds Light on the Need for Systemic Reform”[1]

“Competitors Still Beat U.S. in Tests”[2]

“U.S. students continue to trail Asian students in math, reading, science”[3]

These are a few of the thousands of headlines generated by the release of the 2011 TIMSS and PIRLS results today. Although the results are hardly surprising or news worthy, judging from the headlines, we can expect another global wave of handwringing, soul searching, and calls for reform. But before we do, we should ask how meaningful these scores and rankings are.

“Numbers don’t lie,” many may say but what truth do they tell? Look at the following numbers:

Table 1: Scores and Attitudes of 8th Graders in TIMSS 2011

| Country |

Math Scores |

Confidence (%) (4th Grade) |

Value Math (%) |

| Korea |

613 |

03 (11) |

14 |

| Singapore |

611 |

14 (21) |

43 |

| Chinese Taipei |

609 |

07 (20) |

13 |

| Hong Kong |

586 |

07 (24) |

26 |

| Japan |

570 |

02 (09) |

13 |

| United States |

509 |

24 (40) |

51 |

| England |

507 |

16 (33) |

48 |

| Australia |

505 |

17 (38) |

46 |

These are the scores of 8th graders and percentage of them saying they are confident in math and value math. Top scoring Korea has only 3% of students feeling confident in their math and 14% valuing math, in contrast is Australia with much lower scores but significantly higher percentage of students feeling confident in math and valuing math. In fact, the top 5 East Asian countries in math scores have way fewer students reporting confidence in math and valuing math than the U.S., England, and Australia, all scored significantly lower.

It gives me a headache to understand these numbers: Do they mean that even if the Korean students do not think math is important, they study it anyway? and they have a very effective education that can make people who do not value math to be outstanding in it? Or since these are 8th graders, do they mean that after learning math for 8 years, the students feel the math they have been learning is not important in life? In the case of the United States, do they mean that American students value math but have poor math learning experiences that lead to low math achievement? Or could it be that their 8 years of math learning convinced them, at least a much larger proportion than in Korea, that math is important?

The same questions can be asked about confidence. Do the numbers mean that Korean students lack of confidence makes them study harder so they achieve better in math than their American or Australian counterparts? Or could they mean that the way math is taught in Korea made them lose confidence in math?

The data show that as students progress toward higher grades, they become less confident in their math learning. More fourth graders than eighth graders have confidence in math, for example. Does this mean the more they learn, the less confident they become?

Or perhaps these numbers are not related at all. But the TIMSS report suggests that within countries students with higher scores are more likely to have a more positive attitude towards math, that is, a positive correlation. A negative correlation is found between countries and has been a pattern as Tom Loveless discovered in previous TIMSS. So somehow math scores, attitudes, and confidence are related. Perhaps whatever in an education system or culture that boosts math scores leads to less positive attitude and lower confidence at the same time. In this case, one needs to ask what is more important: scores, or confidence and positive attitude?

There can be other interpretations but whatever the interpretation is, these numbers show that results of TIMSS, or other international assessments such as the PISA, are a lot more complex than what the headlines attempt to suggest: Asians are great, America sucks, so do Australia and England. The TIMSS and PISA scores are perhaps worth much less than politicians and the media make of them, as the rest of this paper shows.

The Numbers Don’t Lie: A Long History of Bad Performance on International Tests

According to historical data, American education has always been bad and actually improving over the years. In the 1960s, when the First International Mathematics Study (FIMS) and the First International Science Study (FISS)[4] was conducted, U.S. students ranked bottom in virtually all categories:

11th out of 12 (8th grade -13 year old math)

12th out 12 (12th grade math for math students)

10th out 12 (12th grade math for non-math students)

7th out 19 (14 year-old science)

14th out of 19 (12th grade science)

In the 1980s, when the Second International Mathematics Study (SIMS) and Second International Science Study (SISS)[5] were conducted, U.S. students inched up a little bit, but not much:

10th out of 20 (8th grade-Arithmetic)

12th out of 20 (8th grade-Algebra)

16th out of 20 (8th grade-Geometry)

18th out of 20 (8th grade-Measurement)

8th out of 20 (8th grade-Statistics)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Number Systems)

14th out of 15 (12th grade-Algebra)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Geometry)

12th out of 15 (12th grade-Calculus)

14th out of 17 (14 year-old Science)

14th out of 14 (12th grade-Biology)

122h out of 14 (12th grade-Chemistry)

10th out of 14 (12th grade-Physics)

In the 1990s, in the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS)[6], American test performance was not the best but again improved:

28th out 41 (but only 20 countries performed significantly better) (8th grade math)

17th out 41 (but only 9 countries performed significantly better) (8th grade science)

In 2003, in TIMSS[7] (now changed into Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), U.S. students were not great, but again improved:

15th out of 45 (only 9 countries significantly better) (8th grade math)

9th out of 45 (only 7 countries significantly better) (8th grade science)

In 2007, U.S. improved again in TIMMS[8], although still not the top ranking country:

9th out of 47 (only 5 countries significant better) (8th grade math)

10th out of 47 (only 8 countries significantly better) (8th grade science)

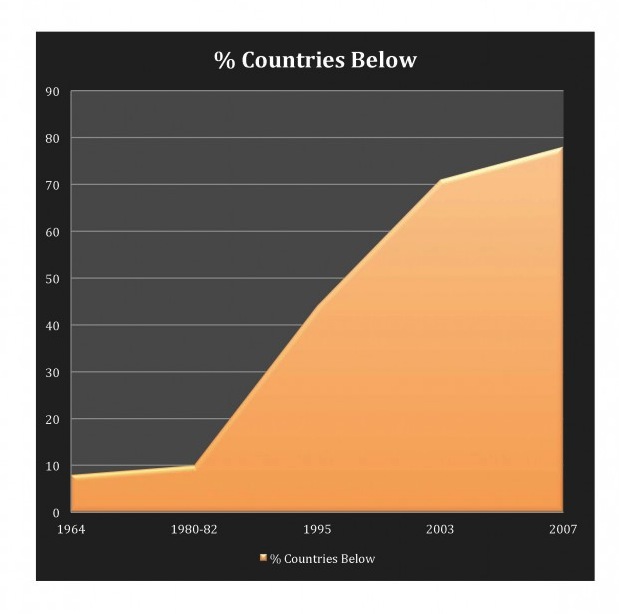

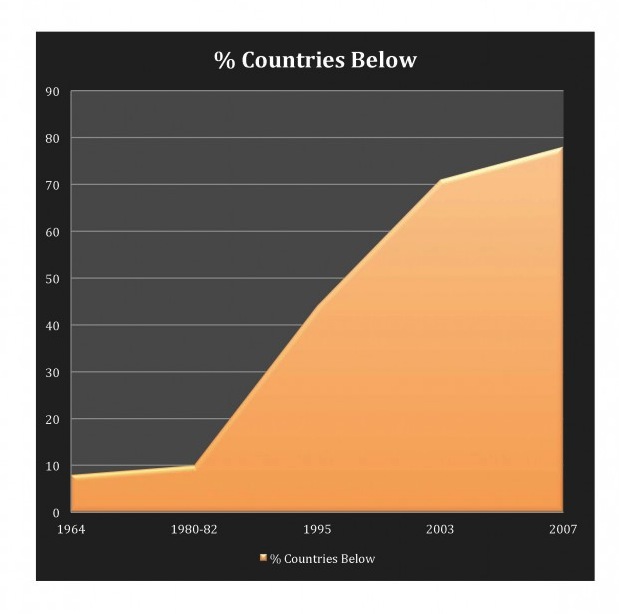

Over the half century, American students performance in international math and science tests has improved from the bottom to above international average. The following figure shows the upward trend of American students’ performance in math. Because 8th grade seems to be the only group that has been tested every time since the 1960s, the graph only includes data for 8th grade math[9].

All the studies mentioned above have been coordinated by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA). There is another international study, one that has gained more momentum and popularity than the ones organized by IEA. This is the Programme for International Student Assessment, better known as PISA, organized by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA was first introduced in 2000 and tests 15 year olds in math, literacy, and science. It is conducted every three years. Because PISA is fairly new, so there is not a clear trend to show whether the U.S. is doing better or worse, but it is clear that U.S. students are not among the best[10]:

PISA Reading Literacy

15th out of 30 countries in 2000

17th out of 77 countries in 2009

PISA Math

24th out of 29 countries in 2003

31st out of 74 countries in 2009

PISA Sciences

21st out of 30 countries in 2003

23rd out of 74 countries in 2009

There are other studies and statistics, but this long list should be sufficient to prove that American students have been awful test takers for over half a century. Some has taken this mean American education has been awful in comparison to others. This interpretation has been common and backed up by media reports, scholarly books, and documentary films, for example:

1950s-1960s: Worse than the Soviet Union (1958, Life Magazine cover story Crisis in Education)[11]

1980s-1990s: Worse than Japan and others (A Nation at Risk[12], Learning Gap: Why Our Schools Are Failing And What We Can Learn From Japanese And Chinese Education[13])

2000s–: Worse than China and India (2 Million Minutes[14] (documentary film) Surpassing Shanghai)[15]

The Numbers Don’t Lie, but What Truth Do They Tell

Numbers can be used to tell stories of the past or the future. We can ask how we arrived at a certain number or what it means for the future. Asking about its past invites us to consider what we did or did not do to achieve a certain state indicated by the number. Asking about its future implications forces us to question if a certain number is desirable or meaningful. The latter must precede the former because unless the state measured by certain numbers has truly significant implications for a desirable future, the question about how we got there is practically a waste of time.

In the case of statistics from international educational assessments, the question about the future has rarely been explored. It has been assumed that these numbers indicate nations’ capacity to build a better future. And thus we must dive in urgently to learn about why others are getting better numbers than us. This assumption, however, may be wrong.

The Numbers’ Future

“Our future depends on the strength of our education system. But that system is crumbling,” reads a full-page ad in the New York Times. Dominating the ad is a graphic that shows “national security,” “jobs,” and the “economy” resting upon a cracking base of education. This ad is part of the “innovative, multitactical” Don’t Forget Ed campaign the College Board sponsored.

It is apparent America’s national security, jobs, and economy has been resting upon a base that has been crumbling and cracking for over half a century, according to the numbers. So one would logically expect the U.S. to have fallen through the cracks and hit rock bottom in national security, jobs, and economy by now. But facts seem to suggest otherwise:

The Soviet Union, America’s archrival in national security during the Cold War, which supposedly had better education than the U.S., disappeared and the U.S. remains the dominant military power in the world.

Japan, which was expected to take over the U.S. because of its superior education in the 1980s, has lost its #2 status in terms of size of economy. Its GDP is about 1/3 of America’s. Its per capita GDP is about $10,000 less than that in the U.S.

The U.S. is the 6th wealthiest country in the world in 2011 in terms of per capita GDP[16]. It is still the largest economy in the world.

The U.S. ranked 5th out of 142 countries in Global Competitiveness in 2012 and 4th in 2011[17].

The U.S. ranked 2nd out 82 countries in Global Creativity, behind only Sweden[18] in 2011.

The U.S. ranked 1st in the number of patents filled or granted by major international patent offices in 2008, with 14,399 filings, compared to 473 filings from China[19], which supposedly has a superior education[20].

Obviously America’s poor education told by the numbers has not ruined its national security and economy. These numbers have failed to tell the story of the future.

The Numbers’ Past

The past stories of numbers lie the lessons to be learned. The problem is that there are different ways to achieve the same number, although a set of factors have been identified to explain why American students perform worse than other countries or what made some other countries achieve better numbers. As a result, the most of the factors become debatable and debated myths, half-truths, or “duh!”

Time. American students spend less time studying. President Obama noted that on average U.S. students attend class about a month less than children in other advanced countries[21] in 2010. His Secretary of Education Arne Duncan said students in China and India attend school 25 to 30 percent longer than in the U.S.[22] A 1994 report of the National Education Commission on Time and Learning established by U.S. Congress observed “Students in other post-industrial democracies receive twice as much instruction in core academic areas during high school.”[23] However a study by the Center for Public Education says “students in China and India are not required to spend more time in school than most U.S. students.”[24]

Engagement and Commitment. American students, schools, parents, and governments don’t take school-based learning as seriously as other top performing countries. Not only students in other countries spend more time in school, “the formidable learning advantage Japanese and German schools provide to their students is complemented by equally impressive out-of-school learning,” noted the National Education Commission on Time and Learning in 1994[25]. “Compared with other societies, young people in Shanghai may be much more immersed in learning in the broadest sense of the term. The logical conclusion is that they learn more…” writes an OECD report explaining Shanghai’s outstanding PISA scores[26]. But the same report immediately notes “what they learn and how they learn are subjects of constant debate.”

Curriculum, Standards, Gateways, and Tests. The U.S. does not have a better (more focus, rigor, and coherence) common curriculum with high standards across the nation and an instructional system with clearly marked transition points. “…standards in the best-performing nations share the following three characteristics [focus, rigor, and coherence] that are not commonly found in U.S. standards,” says a report that calls for international benchmarking by the National Governors’ Association[27]. “Virtually all high-performing countries have a system of gateways marking the key transition points…At each of these major gateways, there is some form of external national assessment,” writes Marc Tucker in Surpassing Shanghai: An Agenda for American Education Built on the World’s Leading Systems (Tucker, 2011, p. 174). But Ontario, a top PISA performer does not, admits Tucker and schools in Finland, a much admired high performer on the PISA, “is a “standardized testing-free zone,”[28] writes Diane Ravitch.

Teachers and Teacher Education. American teachers are not as smart to begin with and are less well prepared than their counterparts in high performing countries. For example, while 100% of teachers in top performing countries –Singapore, Finland and South Korea — are recruited form the top third college graduates, only 23% are from the top third in the U.S., according to a study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Co[29]. Teachers in these top performing countries are also better trained, supported, and motivated before, during, and after taking the teaching job. This is one of the “duhs.”

Inequity and poverty. There is more social economic disparity among U.S. students and higher levels of poverty in the U.S. than other countries. “U.S. students in schools with 10% or less poverty are number one country in the world,” says a report of the National Association of Secondary School Principals[30]. The report establishes a direct connection between PISA performance and poverty and says the U.S. has the largest number of students living in poverty. But others disagree. “The U.S. looks about average compared with other wealthy nations on most measures of family background,” says the report from the National Governor’s Association, “Moreover, America’s most affluent15-year-olds ranked only 23rd in math and 17th in science on the 2006 PISA assessment when compared with affluent students in other industrialized nations.”[31]

There are of course other suggestions from access to natural resources[32] to cultural homogeneity and from sampling bias to parenting styles. Regardless, how each country achieved their international scores is not nearly as straightforward as the numbers themselves, making international learning a very difficult task.

The task becomes perhaps even more difficult, when the issues of economic, cultural, societal, and political contexts are considered. What’s more, learning from others may become not so desirable for the U.S. considering the fact that the test scores have not significantly affected America’s national security and economy. Moreover in the final analysis, since countries that have shown better numbers in tests have not performed necessarily better than the U.S., the U.S. education may have something to offer others.

The Numbers Don’t Lie, but Some Are Missing: Two Paradigms of Education

The fact the U.S. as a nation is still standing despite of its abysmal standing on international academic tests for over half a century begs two questions:

Is education as important to a nation’s national security and economy as important as believed?

If it is, are the numbers telling the truth about the quality of education in the U.S. and other nations?

If the answer to the first question is “no,” we need to disconnect the automatic association between test scores and education. In other words, the numbers don’t really measure education, at least not the entire picture of the education needed to produce citizens to build strong and prosperous economies.

In my latest book World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students[33], I identified two paradigms of education: employee-oriented and entrepreneur-oriented. The employee-oriented paradigm aims to transmit a prescribed set of content (the curriculum and standards) deemed to be useful for future life by external authorities, while the entrepreneur-oriented aims to cultivate individual talents and enhance individual strengths. The employee-oriented paradigm produces homogenous, compliant, and standardized workers for mass employment while the entrepreneurial-oriented education encourages individuality, diversity, and creativity.

Although in general, all mainstream education systems in the world currently follows the employee-oriented paradigm, some may not be as effectively and successfully as others. The international test scores may be an indicator of how successful and effective the employee-oriented education has been executed. In other words, these numbers are measures of how successful the prescribed content has been transmitted to all students. But the prescribed content does not have much to do with an already industrialized country such as the U.S., whose economy relies on innovation, creativity, and entrepreneurship. As a result, although American schools have not been as effective and successful in transmitting knowledge as the test scores indicate, they have somehow produced more creative entrepreneurs, who have kept the country’s economy going. Moreover, it is possible that on the way to produce those high test scores, other education systems may have discouraged the cultivation of the creative and entrepreneurial spirit and capacity.

Unfortunately there are few numbers that directly provide the same kind of comparison as TIMSS and PISA on measures of creativity and entrepreneurship, making it difficult to forcefully prove that American education indeed produce more creative and entrepreneurial talents. A piece of data I have found from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor study suggests a significant negative relationship between PISA performance and indicators of entrepreneurship. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, or GEM, is an annual assessment of entrepreneurial activities, aspirations, and attitudes of individuals in more than 50 countries. Initiated in 1999, about the same time that PISA began, GEM has become the world’s largest entrepreneurship study. Thirty-nine countries that participated in the 2011 GEM also participated in the 2009 PISA, and 23 out of the 54 countries in GEM are considered “innovation-driven” economies, which means developed countries.

Comparing the two sets of data shows clearly countries that score high on PISA do not have levels of entrepreneurship that match their stellar scores. More importantly, it seems that countries with higher PISA scores have fewer people confident in their entrepreneurial capabilities. Out of the innovation-driven economies, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan are among the best PISA performers, but their scores on the measure of perceived capabilities or confidence in one’s ability to start a new business are the lowest. The correlation coefficients between scores on the 2009 PISA in math, reading, and science and 2011 GEM in “perceived entrepreneurial capability” in the 23 developed countries are all statistically significant[34].

Anecdotally, Vivek Wadhwa, president of Academics and Innovation at Singularity University, Fellow at Stanford Law School and Director of Research at Pratt School of Engineering at Duke University, wrote in Business Week in response to the latest PISA rankings:

The independence and social skills American children develop give them a huge advantage when they join the workforce. They learn to experiment, challenge norms, and take risks. They can think for themselves, and they can innovate. This is why America remains the world leader in innovation; why Chinese and Indians invest their life savings to send their children to expensive U.S. schools when they can. India and China are changing, and as the next generations of students become like American ones, they too are beginning to innovate. So far, their education systems have held them back.[35]

But there again are no numbers to prove these. However, other countries, particularly the high scoring Asian countries have all been reforming their education systems to be more like that in the U.S., as I have discussed in my book Catching Up or Leading the Way: American Education in the Age of Globalization[36].

Conclusions

I have put forth a lot of numbers of different sorts from a variety of sources. Taken together, these numbers suggest to me the following:

So far all international test scores measure the extent to which an education system effectively transmits prescribed content.

In this regard, the U.S. education system is a failure and has been one for a long time.

But the successful transmission of prescribed content contributes little to economies that require creative and entrepreneurial individual talents and in fact can damage the creative and entrepreneurial spirit. Thus high test scores of a nation can come at the cost of entrepreneurial and creative capacity.

While the U.S. has failed to produce homogenous, compliant, and standardized employees, it has preserved a certain level of creativity and entrepreneurship. In other words, while the U.S. is still pursuing an employee-oriented education model, it is much less successful in stifling creativity and suppressing entrepreneurship.

The U.S. success in creativity and entrepreneurship is merely an accidental by product of a less successful employee-oriented education, which is far from sufficient to meet the coming challenges brought about by globalization and technological changes. Thus in a sense, the U.S. education is in turmoil, inadequate, and obsolete, but it has to move toward more entrepreneur-oriented instead of more employee-oriented.

[1] http://dropoutnation.net/2012/12/11/americas-woeful-public-schools-timms-sheds-light-on-the-need-for-systemic-reform/

[2] http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324339204578171753215198868.html

[3] http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/us-students-continue-to-trail-asian-students-in-math-reading-science/2012/12/10/4c95be68-40b9-11e2-ae43-cf491b837f7b_story.html

[4] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs92/92011.pdf

[5] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs92/92011.pdf

[6] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/pubs99/1999081.pdf

[7] Data source: U.S. National Center for Educational Statistics: http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results03.asp

[8] http://nces.ed.gov/timss/results07.asp

[9] Since SIMS scores were reported in sub domains, I chose the lowest performance area for the U.S. students: Measurement.

[10] Data source: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/

[11] http://goo.gl/pAgnQ

[12] http://datacenter.spps.org/uploads/SOTW_A_Nation_at_Risk_1983.pdf

[13] http://books.google.com/books/about/Learning_Gap.html?id=HIfBn5W6LMcC

[14] http://www.2mminutes.com/

[15] http://www.amazon.com/Surpassing-Shanghai-American-Education-Leading/dp/1612501036

[16] Data source: International Monetary Fund: http://goo.gl/r7SFQ

[17] http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GCR_Report_2011-12.pdf

[18] Data source: http://www.theatlanticcities.com/jobs-and-economy/2011/10/global-creativity-index/229/

[19] Data Source: Chinese Innovation is a Paper Tiger http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904800304576472034085730262.html?mod=googlenews_wsj

[20] Students from Shanghai China scored 1st on the PISA in all three subjects (math, reading, and sciences) in the last round of PISA released in 2010.

[21] http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/39378576/ns/today-parenting/#.UEPqb2ie7sc

[22] http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Organizing-a-school/Time-in-school-How-does-the-US-compare

[23] http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/PrisonersOfTime/Lessons.html

[24] http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/Main-Menu/Organizing-a-school/Time-in-school-How-does-the-US-compare

[25] http://www2.ed.gov/pubs/PrisonersOfTime/Lessons.html

[26] http://www.oecd.org/countries/hongkongchina/46581016.pdf

[27] http://www.corestandards.org/assets/0812BENCHMARKING.pdf

[28] http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/mar/08/schools-we-can-envy/?pagination=false

[29] http://mckinseyonsociety.com/closing-the-talent-gap/

[30] http://nasspblogs.org/principaldifference/2010/12/pisa_its_poverty_not_stupid_1.html

[31] http://www.corestandards.org/assets/0812BENCHMARKING.pdf

[32] http://www.oecd.org/education/preschoolandschool/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/49881940.pdf

[33] http://zhaolearning.com/world-class-learners-my-new-book/

[34] http://zhaolearning.com/2012/08/16/doublethink-the-creativity-testing-conflict/

[35] http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/jan2011/tc20110112_006501.htm

[36] http://zhaolearning.com/2009/11/14/3/

This is a repost from the blog of Dr. Yong Zhao.